The rapid rise in environmentally responsible or "green" investing has created a considerable new pool of capital specifically targeting green projects.

In response to these developments, companies, financial institutions and governments have begun to issue "green bonds" as a means of accessing this new money. In parallel, a range of "standards" have been developed for issuers to provide assurance to investors that these bonds are green, and for investors to quickly understand the environmental impact of the use of proceeds. As these standards develop, clarity over what merits a bond's treatment as a separate green asset class continues to improve.

In this article, we explore what are green bonds and the standards that are being developed to support investor confidence in the environmental credentials of the green bond market both overseas and in Australia.

The history of green bonds

The market for green bonds is growing rapidly. Reliable estimates show that the global volume of green bonds had grown from less than A$5 billion in 2010 to more than A$150 billion in 2017 and 2018. Australia has come fairly late to the party, having only issued its first green bond in 2014. However, growth has been quick since then, with significant diversification of issuers, from banks to corporates to universities. Click here for a document summarising all Australian green bonds issued to date.

The rapid growth of the market is driven by both investor and issuer considerations.

The investor perspective

The rising popularity of socially responsible investment options, including green bonds, can be attributed to both environmental, social and governance (ESG) and non-ESG investors. ESG investors comprise businesses and individuals wanting to demonstrate ethical and social responsibility by supporting projects that aim to have a positive and sustainable impact on environment and society such as reducing the impact of global warming. Non-ESG investors, on the other hand, are attracted to green bonds on the expectation that, in the long run, these investments will prove to be stronger credits and enjoy a rise in valuation and business prospects in line with a more sustainable business model and the increasing demand for green assets that align with ESG principles. In addition, non-ESG investors may be inclined to use green bonds to balance their risk across a larger number of projects (for example, both renewable and non-renewable energy), enabling them to better manage concentration risk while maintaining liquidity.

For both these groups, the development of universal standards applicable to green bond issuances is likely to build market confidence, by relieving investors of the burden of conducting extensive due diligence to verify the green credentials of their investments.

The issuer perspective

On the supply side, issuers of green bonds enjoy the benefits of a market that is commonly oversubscribed, while also gaining access to new pools of money and greater investor diversification.

Beyond their investor base, engaging in green bond issuances also give companies the opportunity to publicly demonstrate their green credentials, meeting other stakeholders' demands for responsible and sustainable business practices. In addition, while the vast majority of green bonds issued to date have been channelled towards funding renewable energy projects (such as large-scale solar farms), there is an expanding pipeline of other types of green projects to be funded. As a result, opportunities for issuers to engage in green finance initiatives are proliferating as there is now a wider class of assets being used to back green bonds. This is bolstered on the investor side by the availability of clearer standards for green bond issuance, making it easier for issuers to gain certification and secure investor confidence in the greenness of their bonds.

It is also possible that green bonds could have the capacity to price tighter than their non-green counterparts. Although green bonds currently price in line with straight bonds, it is expected that bonds with green credentials will attract a pricing advantage in the future, particularly as the market matures and liquidity improves. This process will likely be accelerated, as the steps involved in preparing, verifying and issuing a green bond have become more streamlined, and the associated costs reduced.

Certification: what makes them green?

The definition of a "green bond" can be subjective, and open to liberal interpretation for public virtue-signalling and marketing to potential investors. However, recent years have seen the development of voluntary standards for green finance initiatives on the international stage. A summary of some of the key standards follow.

Four core components

The Green Bond Principles (GBP), last updated in June 2018, are voluntary, best-practice process guidelines for issuing green bonds. They are aimed at promoting greater transparency, disclosure, reporting and integrity in the developing green bond market. Initially established in 2014 by a collection of investment banks, including Citi, JPMorgan Chase, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs and HSBC (among others), the GBP are now administered by the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) as independent secretariat.

Under the GBP, a "green bond" is loosely defined as any type of bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance or re-finance, in part or in full, new and/or existing eligible green projects which are aligned with the four core components of the GBP. The four core components of the GBP are as follows:

- Use of proceeds. GBP recommend that issuers report on their use of green bond proceeds. This allows funds to be more transparently tracked into environmental projects, providing investors with peace of mind that their funds will be used for the purpose promised by the issuer. In addition, greater insight is possible into the estimated impact of green bonds and their associated projects. To this end, the GBP recognises the following broad green project categories:

- climate change mitigation;

- climate change adaption;

- natural resource conservation;

- biodiversity conservation; and

- pollution prevention and control.

These categories potentially support green projects such as production and transmission of renewable energy, refurbishment of buildings to improve energy efficiency, environmentally sustainable agriculture, clean (for example, electric or hybrid) transportation, infrastructure for sustainable water and waste water management, and so on.

- Evaluation and selection process. According to the GBP, issuers should inform investors of the environmental sustainability objectives of green projects, the process by which they determine how they fit within the eligible green project categories described in the bullet point above, and any related eligibility criteria (for example, any measures employed to manage potential environmental or social risks that could be caused by the projects).

- Management of proceeds. The issuer of a green bond should track its proceeds closely, for example, by crediting them to a sub-account, and separating them with appropriate precautions from the proceeds of any other (that is, non-green) bonds issued. It is recommended that this should be supplemented by an external review by a third party (for example, an auditor) to verify the tracking method and allocation of funds.

- Reporting. Issuers should also keep and make available information on their use of the proceeds from green bonds until their full allocation, both annually and in the case of any significant developments. Here, transparency is of particular value, and the GBP recommend the provision of both qualitative and, where possible (taking into account relevant considerations such as confidentiality agreements and competitive considerations), quantitative indicators of the performance and impact of green projects.

External review of GBP compliance

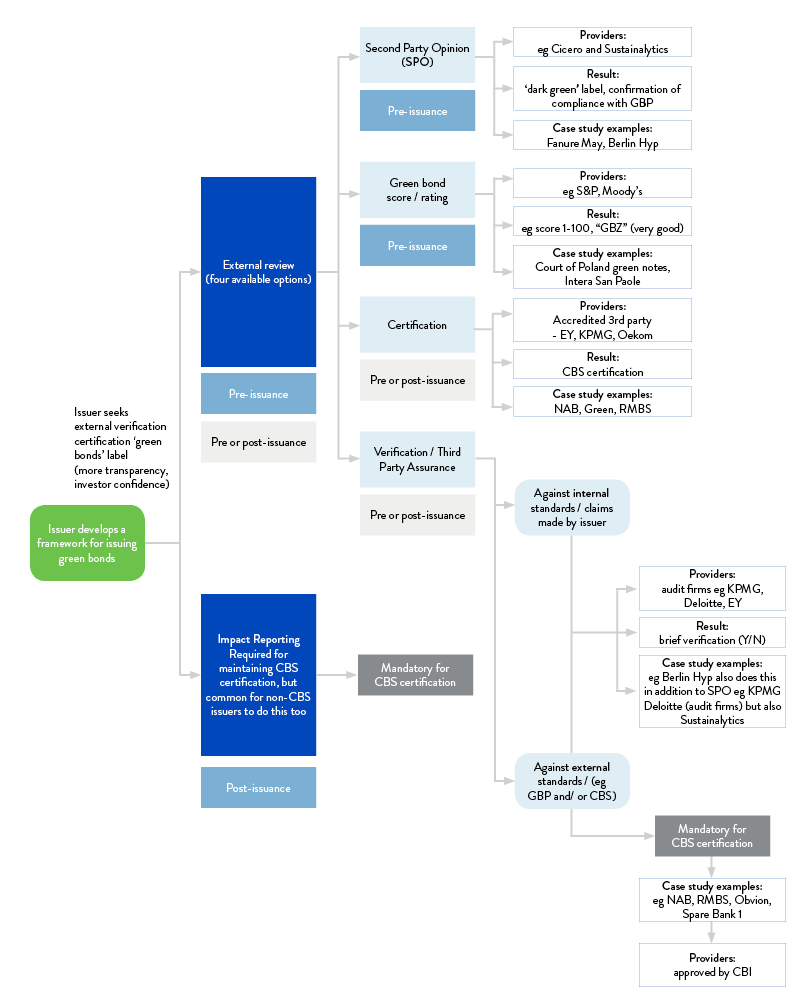

The GBP recommend that, in connection with the issuance of any green bond, issuers should appoint an external review provider or providers to confirm that the bond or bond program is aligned with the four components of the GBP.

Issuers may obtain this confirmation either before or after the issuance of the bond, depending on the type of review obtained, which can include any of the following:

- Second Party Opinion. This is generally carried out before a bond is issued by an independent institution with environmental expertise such as the Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO) and Sustainalytics. The role of the Second Party Opinion provider is to assess the green bond framework used by the issuer to determine which green projects or assets are eligible to be funded by the proceeds raised. This normally entails an assessment of how aligned the issuer's green bond framework is with the GBP. Some Second Party Opinions also provide an additional sustainability rating based on the ESG provider's analysis, for example, CICERO provides a rating based on three 'shades of green' (light, medium and dark green bonds) where the darkness of a bond depends on the alignment of the issuer's framework to a low-carbon economy.

- Green bond scoring/rating. Some credit rating agencies, such as Moody's, RAM Holdings, S&P Global Ratings and R&I, also provide a pre-issuance assessment of a bond's alignment with the GBP as well as the integrity of its green credentials (similar to a Second Party Opinion). Moody's was the first to put forward such a framework for Green Bond Assessments in March 2016. The Moody's framework is aimed at assessing "the relative likelihood that bond proceeds will be invested to support environmentally friendly projects". This assessment is dependent on variously weighted factors, including the issuer's use of proceeds (40%), organisation and environmental governance structure (15%), management of proceeds (15%) and disclosure on use of proceeds (10%). S&P introduced a similar Green Evaluations framework in 2017, producing a score from 0 to 100 largely reflecting the expected lifetime environmental impact of a bond (weighted 60% as a factor in assessment). Additional S&P factors include selection of eligible projects and compliance with environmental regulations (19%), procedures for ensuring proceeds are not used for purposes other than those intended (6%) and transparency (15%).

- Verification, also known as Third Party Assurance. An issuer can also obtain independent verification against a designated set of criteria, focusing on the bond's alignment with either internal or external standards (such as the GBP or Climate Bonds Standard (CBS)) or with claims made by the issuer itself (for example, that 40% of proceeds will go towards refinancing green building loans). This can be carried out either before or after issuance by audit firms such as KPMG, EY and Deloitte. It may also extend to obtaining verification of the issuer's internal tracking of use of proceeds, allocation of funds from proceeds and alignment of reporting procedures with the GBP. In contrast to a Second Party Opinion, verification is usually more of a rubber stamp - a yes/no question of compliance – and the resulting reports (Assurance Reports) are typically much shorter in their final form. If the issuer is also seeking certification under the CBS, this step is usually a prerequisite to obtaining this. For more information on the CBS, see Role of the Climate Bonds Initiative and Climate Bonds Standard.

- Certification. An issuer can have its green bond or associated green bond framework certified against a recognised external green standard or label that is aligned with the GBP. Achieving certification will provide independent assurance to investors that the green bond offering will satisfy the requirements of the GBP. This too can occur either before or after issuance. These standards or labels define specific criteria, alignment with which is usually left to be determined by an accredited third party. The CBS is perhaps the most prominent example of such an external green standard or label (see Role of the Climate Bonds Initiative and Climate Bonds Standard). In effect the CBS converts the GBP into a set of requirements that can be assessed, assured and certified. A number of third party organisations have been officially trained and qualified to verify an issuer's alignment with the CBS, including EY, KPMG, Oekom Research, Sustainalytics, Trucost, PWC, Deloitte, Multiconsult, and others. We note that some of these audit firms and ESG providers are also providers of Second Party Opinions and Assurance Reports, but apply separate, more streamlined procedures when assessing certification under the CBS. In order to maintain a CBS certification, the bond is also subject to mandatory annual impact reporting. For more information on impact reporting, see Impact reporting.

The following diagram summarises the relationship between these roles.

Impact reporting

Audit firms, Second Party Opinion providers, or issuers themselves may engage in post-issuance reporting, seeking to quantify the environmental impact of an asset or project funded by a green bond. This is often employed on an ongoing basis in addition to one or more of the four options (see Four core components). Whether an issuer engages in impact reporting is an increasingly important consideration for many investors and market stakeholders. This is particularly the case as green bonds are backed by a broadening range of assets, for example, by low carbon infrastructure, as opposed to renewable energy projects, whose positive environmental impact is less complicated. Although impact reporting is not essential to differentiating between a green and non-green asset, it is a requirement for CBS certification and under most market guidelines, including the GBP. For example, CBS certification requires issuers to report at least annually on the projects and assets being funded by the bond and their ongoing eligibility as well as the use of proceeds. Annual reporting is also recommended by the GBP.

Related standards

In November 2017, the ASEAN Capital Markets Forum issued the ASEAN Green Bond Standards (AGBS) to provide specific guidance on how the GBP are to be applied across the ASEAN region to be recognised as ASEAN Green Bonds. AGBS largely replicate the GBP, subject to some key differences including a requirement that the issuer has a geographical or economic connection to the ASEAN region. Further, the AGBS explicitly exclude fossil fuel power generation projects from being eligible for ASEAN Green Bond Standard issuance.

Alongside the GBP, ICMA supported the launch of the Green Loan Principles (GLP) in March 2018 by the Loan Markets Association (LMA) and the Asia Pacific Loan Market Association (APLMA). ICMA also published the Social Bond Principles (SBP) and the Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBG) in June 2018. A summary of these supplementary guidelines follows.

Social Bond Principles (SBP)

The SBP are voluntary process guidelines that clarify the approach for issuance of a social bond (also called social impact bonds or SIB). SIB issued under the SBP framework are any type of bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance eligible social projects aligned with the four components of the SBP, which essentially mirror the four components of the GBP, subject to adjusted requirements to reflect the social objects of the bonds.

|

Notable examples of Australian issuances of SIBs include:

|

Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBG)

In recognition that social projects can have a strong green element to them, and vice versa, ICMA has also developed the SBG to provide guidelines for bonds combining green and social projects. Classification as a green or social bond should be based on the primary objective of the underlying project. However, where the proceeds will be applied to both green and social projects, the bond can be classed as a sustainability bond, if it complies with the four core components of both the GBP and the SBP. Confirmation of this approach is set out in the SBG.

|

Recent examples of Australian issuances of Sustainability Bonds include:

|

Green Loan Principles (GLP)

The GLP are the equivalent of the GBP for green loans rather than green bonds. The GLP aim to create a high-level framework of market standards and guidelines, providing a consistent methodology for use across the wholesale green loan market, while allowing the loan product to retain its flexibility, and preserving the integrity of the green loan market while it develops. The GLP build on and refer to the GBP, with a view to promoting consistency across financial markets.

Green loans are defined in the GLP as "any type of loan instrument made available exclusively to finance or re-finance, in whole or in part, new and/or existing eligible Green Projects". The "eligible Green Projects" are based on the same list of eligible green projects that apply under the GBP, and include production and transmission of renewable energy, pollution prevention and control, sustainable natural resources management, biodiversity conservation, climate change adaptation and green buildings.

The GLP set out a clear framework of recommendations, to be applied by market participants on a deal-by-deal basis depending on the underlying characteristics of the transaction. The GLP recommendations are based on the four components of the GBP, adjusted to reflect the requirements of loans.

|

Macquarie Group was the first financial institution to issue a green loan under the GLP. The green loans were issued under a £2.0 billion loan facility, which included a £500 million facility to finance green projects. The green tranches will be used to support renewable energy projects initially, and energy efficiency, waste management, green buildings and clean transportation projects in the future. Macquarie Group intends to utilise market-leading, proprietary green impact assessment and reporting for eligible projects, developed by its Green Investment Group. |

Role of the Climate Bonds Initiative and Climate Bonds Standard

The Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) is an international, investor-focused not-for-profit organisation working to mobilise the US$100 trillion bond market for climate change solutions. Its key focus is to develop policy models and advice for governments and corporations, develop agreed definitions and standards for green bonds, and help countries develop proof-of-concept projects and bond issues. The launch of the CBS in November 2011 was one of the early initiatives of the CBI.

CBI pitches its CBS as a "Fair Trade-like labelling scheme for bonds", allowing investors to confidently classify and prioritise low carbon and climate resilient investments, and removing the need for subjective judgment or extensive due diligence by investors themselves. It is aimed at ensuring that issuers of green bonds have established appropriate internal processes, controls and reporting procedures, in addition to meeting sector-specific criteria which determine the requisite greenness of eligible bonds (for more information on sector-specific criteria, see CBS sector-specific criteria).

Importantly, the CBS provides an opportunity for the kind of external "certification" broadly recommended by the GBP. Issuers who opt for CBS certification will find that it goes into greater detail than the GBP in relation to the definition and benchmarks for eligibility as green bonds. The CBS certification scheme requirements are based on a long-term target of zero emissions by 2050 in line with the Paris Agreement. Some issuers, like the World Bank, Fannie Mae and Berlin Hyp have stated their commitment to the GBP, but have chosen to develop their own criteria for green bond eligibility in lieu of seeking certification under the CBS.

Development and contents of the Climate Bonds Standard

The CBS, now in version 2.1, was last updated in July 2018. Version 3.0, however, is currently being finalised with a view to being released during the course of 2019, and will incorporate the most recent GBP in order to reinforce the international applicability and consistency of the framework. The new version will include increased requirements for disclosure, more clarity regarding reporting requirements prior to and following bond issuances, clearer green definitions and a larger focus on green loans, among other amendments.

The current CBS provides an extensive taxonomy of green project and asset types eligible for CBS certification, consisting of the follow seven categories:

- Renewable and alternative energy (for example, solar energy, wind energy, hydropower, geothermal energy and energy storage systems).

- Energy efficiency (for example, commercial and residential green building, energy efficient products and waste heat recovery).

- Low carbon transport (for example, national rail and freight systems, urban rail systems, electric vehicles, alternative fuel vehicles and fuel efficient vehicles).

- Sustainable water (for example, storm water adaptation investment, and water treatment and recycling).

- Waste, recycling and pollution (for example, industrial recycling, recycled products, composting and technologies that reduce and capture greenhouse gas emissions).

- Sustainable agriculture and forestry (for example, afforestation, that is, plantations on non-forested degraded lands, reduced water use and verifiable reduced fertiliser use).

- Climate resilient infrastructure and climate adaptation (for example, bridges and rail to protect against increased rainfall).

In addition, the CBS sets out exclusions, which deem certain assets or projects ineligible for selection including, for example, rail lines where fossil fuels account for more than 50% of freight, waste incineration without energy capture, and uranium mining for nuclear power.

The practical requirements that CBI-certified bonds must satisfy under the current version of the CBS include:

- Pre issuance requirements, in relation to:

- selection of nominated projects and assets;

- creation of internal processes and controls for tracking of proceeds, managing unallocated proceeds and earmarking funds to nominated projects and assets (in line with the GBP);

- reporting prior to issuance; and

- a list of eligible bond structures, which has been expanded to include residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), covered bonds and other structures.

- Post issuance requirements, in relation to:

- nominated projects and assets;

- use of proceeds;

- non-contamination of proceeds; and

- annual reporting (for example, on the progress of green projects or assets being funded by the bonds).

CBS sector-specific criteria

The CBI's Technical Working Groups, consisting of key industry experts, have developed seven sector-specific standards so far, setting out criteria for investment in wind, solar and geothermal energy, low carbon buildings, water infrastructure, low carbon transport and marine renewable energy. In turn, these standards provide detailed definitions of greenness that are also sector specific, developed by scientists and industry experts.

Focusing on the Low Carbon Buildings Criteria by way of example, this was developed through CBI's Low Carbon Buildings Technical Working Group in 2014, and is the framework now used to verify green commercial and residential mortgage backed securities worldwide. In relation to both residential and commercial buildings, the criteria uses local building codes and energy ratings or labels as a proxy to determine whether a building's performance falls in the top 15% of buildings in a city. After this determination, a declining threshold is created for that city: starting at the top 15% and then going down to 0% by 2050. This is currently being done for the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Where actual building data is not available, proxies are put in place as mentioned above.

|

Low carbon commercial buildings In May 2015, Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ) was one of the first Australian banks to secure CBI certification over a A$600 million issuance of green bonds partially backed by low carbon commercial buildings. This asset-backed security was ANZ's first green bond issuance, with 40% of the assets backing the bond comprised of Green Star 4 Star-rated commercial buildings, and wind and solar assets making up the other 60%. 77% of the assets were located in Australia, with the remainder in New Zealand, the Philippines and Taiwan. However, all the commercial buildings included were Australian. Since then, National Australia Bank (NAB), Westpac, Commonwealth Bank, Monash University, the Treasury Corporation of Victoria and Investec have also issued CBI-certified bonds partly backed by low carbon commercial buildings or building upgrades. In February 2018, NAB launched the world's first mixed green building bond, a A$2 billion RMBS securitisation that includes a A$300 million green Australian residential properties tranche. The green tranche was the first Australian RMBS to meet the CBS criteria for Australian low carbon residential buildings. |

Low carbon residential buildings: green residential mortgages in Australia

In July 2017, CBI released its first qualifying criteria under the CBS tailored to Australian residential mortgages called the Low Carbon Residential Buildings Proxy Criteria (Proxy Criteria).

In the criteria, CBI sets out the location-specific requirements that Australian residential buildings "must satisfy to be eligible for nominated use of proceeds in a Certified Climate Bond". These are intended to evolve (that is, become stricter) over the coming years, in order to achieve the 2050 target. Accordingly, CBI intends to review the proxies (see Proxies for Australian residential properties) for residential properties in Australia on a bi-annual basis.

Though currently limited to New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania, it is also expected that the criteria will be updated over time to allow properties in other states and territories to qualify for green mortgages. CBI is also working on proxies for other sources of building data such as rooftop solar data.

The Proxy Criteria are based on the minimum design standards for thermal efficiency and energy efficiency of Australian residential buildings within the selected states. To this end, CBI evaluated local building codes and energy rating schemes in these states to determine which were in line with the "decarbonisation trajectories" required by the Paris Agreement.

On this basis, residential buildings are eligible for certification if they meet one of the following approved proxies:

Proxies for Australian residential properties

|

State |

Requirement |

Maximum Weighted Average Life |

Details |

|

New South Wales |

BASIX Energy 40 |

eight years |

New houses approved in the Sydney Local Government Area after June 2004 will be deemed to qualify New houses approved in other areas of NSW after July 2005 will be deemed to qualify Apartments will only qualify by demonstration of BASIX Energy 40 certification |

|

Tasmania |

BCA 2013 |

12 years |

New houses and apartments approved under NCC BCA 2013, introduced 1 May 2013, or later will be deemed to qualify This coincides with the introduction of a 6 Star NatHERS requirement |

|

Victoria |

BCA 2011 |

six years |

New houses and apartments approved under NCC BCA 2011, introduced 1 May 2011, or later will be deemed to qualify This coincides with introduction of a 6 Star NatHERS requirement |

As set out in the Proxies for Australian residential properties table, the most relevant locally applicable standards for CBI certification at present are the Building Sustainability Index (BASIX), the National Construction Code's Building Code of Australia (NCC BCA) and the National House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS).

Introduced in July 2004, BASIX is implemented under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) and is part of the New South Wales development application process. It aims to reduce water and energy consumption in residential properties across the state. BASIX Energy Targets range from ten to 50, and Water Targets from 20 to 50. A BASIX Energy Target of 40 (as referenced in the Proxies for Australian residential properties table) means that a new home will on average produce 40% less greenhouse gas emissions than a pre-BASIX home.

The National Construction Code comprises of the Building Code of Australia and, since 2011, the Plumbing Code of Australia (Code). The Code is given legal effect by relevant implementing legislation in each state and territory, which prescribes or "calls up" the NCC to fulfil any technical requirements that are required to be satisfied when undertaking building work.

Finally, NatHERS uses computer simulations to determine the potential thermal comfort of Australian homes on a scale of one to ten stars. The more stars a residence has, the less likely its occupants will need cooling or heating to stay comfortable (and, for sustainability purposes, the less greenhouse gases the residence will generate). Ratings calculations take into account factors such as building materials, location, size of openings such as windows, type of construction and other relevant factors.

NatHERS ratings tend to correlate most strongly with emissions in places were heating is the predominant use of energy, such as Tasmania and Victoria. Conversely, in New South Wales and Queensland, where cooling is the predominant energy use, correlation between ratings and emissions is much weaker. Accordingly, further standards may need to be developed in coming years to assist with ongoing subscription to CBI criteria, in order to better gauge the energy efficiency of homes in warmer Australian climates.

Steps and procedure for bond certification and issuance under the CBS Certification Scheme

A summary of the steps and procedures to be followed by issuers for bond certification and issuance under the CBS Certification Scheme follows.

|

Steps |

Procedures |

|

1. Prepare the bond for labelling |

This requires that the issuer to:

|

|

2. Engage a third-party verifier |

|

|

3. Certification |

|

|

4. Issuance |

|

|

5. Post-issuance certifications |

|

|

6. Report annually |

|

Non CBI-certified green bonds

The green integrity of the green bond market is supported not only by CBI, but by a range of non-CBI certified issuers and certification schemes.

For example, as of November 2018, the World Bank had issued over 150 green bonds in 20 currencies since 2008, bringing it to a total of over US$13 billion. Though backed by a variety of projects, these green bond issuances are broadly designed to fund climate investment in developing countries as part of the approximate US$50-60 billion a year the World Bank raises in the global capital markets with the goal of eradicating extreme poverty and promoting sustainable development.

In determining what projects qualify as green enough to be funded by its green bonds, the World Bank has generated its own eligibility criteria. These criteria were independently reviewed by the CICERO at the University of Oslo, and were deemed to provide "a sound basis for selecting climate-friendly projects". World Bank green bonds now support 91 climate change mitigation and adaptation projects in 28 countries, including projects in renewable energy and energy efficiency, water and waste management, agriculture, land use and forestry, resilient infrastructure, and sustainable transportation. Specific projects have included increasing the energy efficiency of households in Mexico by replacing incandescent lightbulbs with compact fluorescent lights, and working with the Colombian government to improve urban transportation by replacing old buses with safer, more fuel efficient models.

At a national level, a primary example of an independent green RMBS issuance is the scheme set up by the Federal National Mortgage Association (commonly known as Fannie Mae) in the United States. Fannie Mae has its own Green Bond Certification process for green mortgage-backed securities which, similar to CBI's proxy criteria, is dependent on pre-existing market standards, such as local and national energy ratings schemes. In contrast to traditional RMBS, Fannie Mae generally does not issue green bonds backed by bundles of multiple mortgages, but instead, typically issues bonds based on an individual mortgage over a single residential property. However, in 2017, Fannie Mae launched its first DUS Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit under which a special purpose vehicle is used to pool and re-securitise a portion of the already-issued green mortgage-backed securities to back further bond issuances of green bonds. Though still not certified under the CBS, Fannie Mae has obtained a Second Party Opinion from CICERO which gave this issuance a light green rating.

In Europe, German commercial real estate financing bank Berlin Hyp issues two types of green bonds: covered bonds and senior secured bonds, both issued and documented under its unified Green Bond Program. Like Fannie Mae, Berlin Hyp remains uncertified by CBI, but has commissioned Oekom Research AG to independently assess the program's sustainable value (that is, provide a Second Party Opinion) and to report annually on the bank's compliance with the criteria defined in the Green Bond Program. In the unique Green Bond Framework developed for the program, Berlin Hyp has also stated its commitment to the GBP, and confirmed that each bond issued under this framework must align with its four pillars. For more information on the four pillars under the GBP, see Four core components.

Green bonds prospects for 2019

An August CBI report has noted that the cumulative green bond issuance in Australia to date is approximately A$8 billion. Despite a challenging policy backdrop, Australia has emerged over the last four years as an example of world's best practice in market development, with commitment from the major banks and a diversity of green bond issuances including from two state governments, the property and tertiary sectors, and high levels of certification.

Notwithstanding this positive story, the report observes that still more needs to be done by Australia to reach its current climate targets. In particular, it points out that investing in clean infrastructure is one of the most effective ways for Australia to reach its current climate targets, while also preparing for a potential ratcheting up of international emissions goals. Other acknowledged benefits of this investment strategy include the potential for this investment to spur innovation, broaden the economic base, reduce urban congestion, improve the liveability of cities and support sustainable economic development and social well-being.

Examples of some of the clean infrastructure asset classes that are likely to deliver the best opportunities for growth in Australia's green bond market are:

- Transport and energy.

- Green RMBS linked to existing and new building codes.

- Climate resilient and adaptive water infrastructure, sustainable management and resilient agricultural practices.

- Recycling, reuse and waste processes.

There is also potential for growth in asset classes that traditionally support the asset-backed security market including electric vehicles, solar panels, charging infrastructure, green loans, green mortgages (residential and commercial) and possibly green fintech.

Although the Australian bank sector is expected to continue to dominate issuance, diversification from the listed non-bank sector is predicted to increase as climate risks and opportunities are given increased weighting in their forward capex decisions.

At a global level, leading Nordic bank and green bond specialist SEB has predicted the green bond market should grow from around US$180 billion in 2018 to US$210 billion in 2019, with the potential to "surprise to the upside" and reach US$240 billion.

These predictions take into account the prospective scale of the green infrastructure investment pipeline, and more issuers across new sectors and geographies finding deeper pools of projects and activities to fund on their balance sheets. It is also expected that 2019 will see the launch of the first green collateralised loan obligations, and the introduction of new government policy incentives to stimulate additional investment.

The continued development of guidelines, best practices and certification schemes to underpin trust and transparency in green bond issuance will be critical to support the growth of this market.

Download the table that summarises green and sustainability bonds issuances by Australian corporates domestically or globally here.

KNOWLEDGE ARTICLES YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN:

Visit SmartCounsel