“My data is your data” and, equally so, “your data is my data”. Both hold, depending on your perspective.

Just as quickly as organisations are realising the value of their data assets, we are moving to a point where those assets are not really ours. At least not in a legal sense.

There is an intersection of issues:

1. We are seeing a dramatic increase in consumer protections regarding data. We are not talking only of privacy, although that is the cornerstone.

2. Consumer rights to data and notions of data portability are being strengthened, both in Australia and globally. See our previous article on developments in this space - Open Banking Regime Across the Globe.

3. Competition policy is increasingly delving behind corporate control of data assets and preventing the use of data as a barrier to protect from competition.

4. A shift in community attitudes that, regardless of legal or regulatory intervention, are pushing organisations to acknowledge the shared interests and rights in data assets – far more than before.

5. Last, but not least - Governments and organisations alike are increasingly recognising the true value of their data is not realised by keeping it in silos, but instead, by sharing.

So what does this mean?

It means life is becoming complicated for data holders.

It used to be easy: You used to assume that the data you held was yours and you could do what you wanted with it. Of course, this assumption never truly held, but ignorance was bliss for many.

The largely siloed structure of the corporate economy – where competition policy designed to limit sharing and interaction between competing businesses – has, for the most part, kept the data landscape simple. Data was generated from customer interactions and maybe a handful of third party interactions from key suppliers. That was largely it for all but the largest corporations.

Data governance wasn’t considered big issue on this basis.

But what about today?

We all know the amount of data produced is increasing exponentially. It shows no sign of slowing down.

But the sheer volume of data is only a small part of what makes today different from yesterday. The key change is that corporate relationships are far more complicated. Which means the data landscape is also more complicated.

We are quickly moving towards a platform-based economy with even the big banks looking at a future where their core business may evolve to be a distributor of products, some of which are theirs, but many of which are third party owned. Further, we have moved to a sharing economy – where information, assets and infrastructure are being shared for efficiency and productivity, and to enhance competition.

This is a fundamental shift.

In short, we now have, more than ever, an ecosystem model. Each business and its profitability is heavily dependent and heavily integrated with others, including in many cases with its competitors. Seeking to stand as a siloed, self-sufficient organisation is becoming increasingly challenging.

Behind the scenes of this shift in the economy, we have an increasingly broad, fragmented and distributed web of corporate relationships, both domestically and globally.

Gone are the days where large corporations had only a few big third party relationships. Now we have an ever increasing web of third party arrangements, as suppliers, as partners, as distributors, as referrers, as JVs or others.

Supply chains are longer and more diverse and most, if not all parts, of any business, can now be outsourced. Business processes are being offshored or performed by teams of robots managed by third party vendors.

So what does this mean for data?

Given the fragmentation of supply chains and the platform or ecosystem based nature of the new economy, data is being piped into organisations from such a broad range of sources that it is difficult to track and manage.

The payments industry is a prime example – at its simplest, data starts in a point of sale system, goes to a merchant terminal, to an acquiring bank, through a card scheme, to an issuing bank and then back again. This is before you start talking about mobile wallet providers, payment gateway providers, tokenisation service providers and the other intermediaries who all play a role and touch or handle data as it is piped through the network. Of course, you then need to overlay all of that with software vendors, outsourced service providers, contact centre providers and other third parties the banks and others contract to manage and operate parts of this ecosystem. You very quickly end up with a long list of third parties, many of whom process, add to, modify or transform the data along its journey.

Every piece of that data comes with baggage. Baggage in the form of restrictions, rights and obligations.

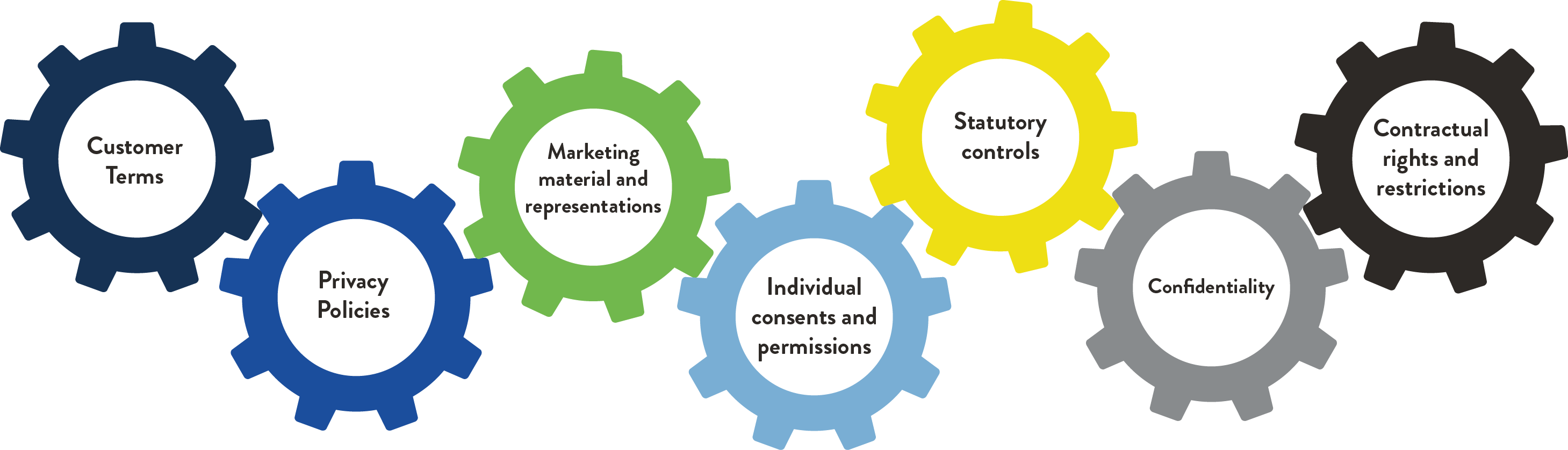

This can be the form of:

- customer terms specifying that data will only be used for the purposes of providing the service

- privacy policies

- marketing material talking about your data security

- obligations of confidence

- contractual rights and restrictions

- statutory controls and limitations or

- individual customer consents or permissions.

Sitting above all these legal frameworks, of course, are issues of social licence, ethics and customer expectations.

Suffice to say, managing and protecting data is a tangled web.

And this web is becoming increasingly complicated. The most recent example of this is the new Consumer Data Right which is being framed up in Australia. While the intent and objective are clearly laudable, the regime does creates yet another layer of data and privacy protection to the existing regulatory regime. That is, the Consumer Data Right regime includes new, stricter consent requirements and “Privacy Safeguards” which overlay with the existing consent and privacy protections under the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).

And so, the plot continues to thicken…

Data governance in the platform and ecosystem economy

So, we now have two key ingredients:

- an increasingly complex set of corporate relationships flowing from the platform and ecosystem economy; and

- an increasingly complex set of data controls and data protection frameworks.

The culmination is that not only is it more difficult for organisations to properly manage their own data assets but, equally so, it is difficult for them to trust others with the data that they share.

This too has been borne out in the discussions regarding the Consumer Data Right – issues of security and liability have been, and still are, front and centre. Accreditation regimes are useful to manage this risk, and statutory stipulations with respect to liability are also helpful. However, the fact remains that data breaches occurring anywhere in the ecosystem have a strong likelihood of coming back to cause difficulties for the original data holder. They hold the primary customer relationship, so are a likely target for both customer claims and also any fraudulent or malicious act using the compromised data. Even where there is no fault or legal liability, this may result in cost and loss.

So, when data sharing does occur, it usually comes with tight controls on how it must be handled and often strict risk allocation regimes. In addition, audit and monitoring rights are also often required as in many circumstances it is not enough to simply contractually allocate the risk.

The Royal Commission into the Financial Services Industry, amongst other things, highlighted that it is not sufficient for organisations to simply have contractual terms with third parties that require them to do the right thing. Oversight, monitoring and auditing is expected and required.

When applied to data ecosystems this can be difficult and costly.

All of this compounds our “baggage” problem referred to earlier and, when applied in a world where it is important to be agile, easy to do business with, and “fast to contract”, it creates friction in an economy and environment which can and does stifle competition and innovation – the very things data sharing should be enabling.

Standardisation and harmonisation

So, there is a clear balancing act to be performed between the regulation and protection of data assets and interests in them, both for consumer and companies, and the free and open use of data to achieve the goal of true innovation.

It is not necessarily difficult to strike this balance correctly. Many would argue the GDPR is close. Many argue that the Consumer Data Right in Australia is also close.

However, the difficulty is not being able to start with a blank piece of paper and create a single well designed (ideally, global) regime.

The current legal framework is a patchwork of consumer rights, competition policy, privacy, intellectual property and confidentiality. There are also industry specific regimes, particularly in health and telecommunications. All of this complexity gets magnified across the various jurisdictions, most of which now have extra-territorial reach.

So organisations are left with difficult questions:

- Do I set up data architectures and governance to allow me to manage to each of the different frameworks that apply to each data set?

- Do I take the high water mark and manage to that?

- Do I curtail my business practices to avoid attracting costly data compliance regimes?

- Do I take a risk based approach in some instances and hope for the best?

- Or, all of the above, in different measures.

Again, it’s an issue of friction. The challenge with the data economy is that it is not efficient by design. The regulators in this space will often call for “privacy-design” or “compliant-by-design” - a notion that issues of privacy and regulatory compliance are considered from the ground up as part of the design.

The same type of thinking needs to be applied to data governance and regulation. To realise the innovation and economic efficiency potential the data economy holds, data regulation needs to be efficient.

Standardisation and harmonisation of data regulation is of course a very difficult thing to achieve on a global level. It is a lofty goal, but one which perhaps we should, by design, try to achieve.

If we don’t as a global economy set out to do this in a structured, planned manner, the combination of the far more integrated global ecosystem means that the strictest data protection regime may well default to become the global standard – it being the “high water mark” that needs to be adopted.

This may, or may not, strike the balance that is needed.

Authored by Simon Burns

Visit SmartCounsel