Just over a year ago, we issued an alert on a decision by Justice Tony Pagone of the Federal Court (now retired and practising at the bar) that threw the taxation of limited partnerships into disarray with a controversial decision in Resource Capital Fund (RCF) IV. Some of our observations were also quoted in the AFR.

What is not apparent in either publication is our expectation that Justice Pagone’s decision would be overruled on appeal. The Full Federal Court, comprised of five judges, has handed down its judgement, resoundingly rejecting the lower court’s approach to the taxation of limited partnerships.

Unfortunately, despite attempting to be determinative in its decision, there are a number of issues highlighted by the Court's decision that taxpayers will need to resolve. The evidential aspects of the case may mean that either the Commissioner of Taxation (Commissioner) or the taxpayers may seek leave to the High Court, further extending the uncertainty.

What are limited partnerships

In a general law partnership, the partners carry on business in common with a view to a profit. The liability of partners is unlimited. By contrast, the liability of at least one partner (referred to as the limited partner) in a limited partnership is limited, whereas the liability of at least one partner (referred to as the general partner) is unlimited.

Limited partnerships are a common investment structure, particularly for investors based in the United States. They are commonly based in the Cayman Islands or in Delaware because of the US tax benefits of those jurisdictions. Their place of incorporation is not motivated by any Australian tax considerations and does not provide any Australian tax advantages.

Limited partnerships are also becoming common in Australia, particularly in the venture capital space. However, venture capital limited partnerships and early stage venture capital limited partnerships are not affected by the decisions in RCF IV due to their peculiar tax regime (references in this alert to limited partnerships do not include these types of limited partnerships). It is also Government policy to introduce a collective investment vehicle that is structured as a limited partnership; however, this structure is still in development.

The taxation of limited partnerships

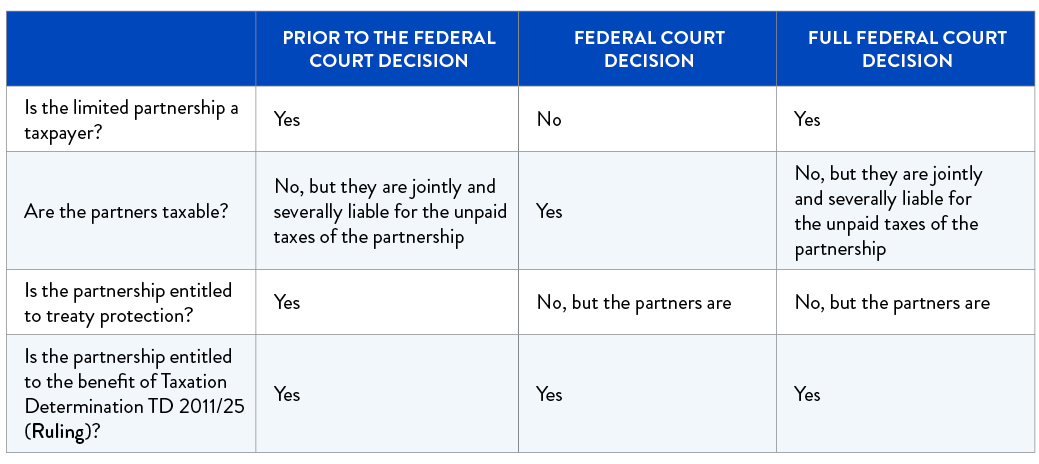

The table below summarises the differing treatment of limited partnerships and their partners:

Let us look at the Full Federal Court’s decision more closely.

Limited partnerships are taxpayers

The Full Federal Court sensibly held that limited partnerships are companies for the purposes of the income tax law. As such, they are entities that are liable to pay income tax. This is patently the objective and intention of the limited partnership provisions in the income tax legislation. It is also consistent with a number of Interpretative Decisions that the Commissioner has historically issued (see, for example, ATO ID 2006/334 in a slightly different context).

To conclude otherwise would make the entire limited partnership provisions and a range of interaction provisions redundant. Fundamentally, such a contrary conclusion would not give weight or effect to the words of the legislation.

Following from this conclusion, it is the limited partnership that has standing before the Court in respect of appeals. It is the entity that is assessed and is able to object against that assessment. The partners have no such standing (except for the limited purpose discussed next).

Partners are jointly and severally liable for the income tax liabilities of the limited partnership

Recognising that a limited partnership is not a legal person and is therefore not capable of being sued, the income tax law makes the partners jointly and severally liable for the income tax liabilities of the partnership. The law ensures “that persons capable of being sued in debt are made liable for the … limited partnership’s liability for [income] tax”.

Although the conclusion is no doubt correct, the reasoning fails to address two matters:

- A limited partner could be an entity that is not a legal person. For example, a trust could be a limited partner; another limited partnership could be a limited partner. In both examples, there is a legal person that potentially has capacity to be sued – the trustee and the general partner.

- A limited partner has limited liability. Section 60 of the Partnership Act 1892 in New South Wales makes this clear. Therefore, a Commonwealth statute is seeking to expand the liability of a limited partner beyond the maximum amount of liability prescribed by State law. Although this contest can be resolved in an entirely Australian context by the Constitution (the Commonwealth statute takes precedence to the extent of the inconsistency), it does not adequately address the conflict with international laws under which a limited partnership may be formed.

Limited partnerships cannot rely on the tax treaties

The Court’s decision in RCF IV only looks at the US-Australia double tax treaty. Although the decision did not consider other treaties, the same principles should apply subject to the precise wording of the relevant treaty.

Under the US-Australia treaty, only a “resident” of the US can invoke the protections of the treaty. A limited partnership is resident in the US for the purposes of the treaty if, broadly, it is resident in the US for the purposes of US tax, and only to the extent that the income of the partnership is subject to US tax as income of a resident, either in the hands of the partnership or of a partner.

Lack of evidence

The Court concluded that the RCF limited partnerships were not residents of the US for the purposes of the treaty because there was no evidence before the Court that the income of the partnerships was subject to income tax in the US.

This is such a significant matter relevant to the application of the treaty and it is astounding that RCF failed to lead sufficient evidence in this regard, although there may well have been sound commercial and confidentiality reasons why this may have been the case. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that the Full Federal Court could have remitted the limited question on the limited partnerships’ residency back to the Federal Court.

This aspect of the decision highlights the incredible importance of case management in tax disputes (see the section below). This would have been a simple matter for RCF to provide evidence on – tax paid by just one partner in the US would have sufficed.

Dual requirement

In a strange turn of proceedings, it was RCF (not the Commissioner) who argued that the RCF limited partnerships were not residents of the US for the purposes of the treaty. RCF contended that the concept of a resident for the purposes of the treaty had two elements, both of which needed to be satisfied: the first was that the relevant partnership must be a resident of the US for the purposes of US income tax, and the second was that the income of the partnership must be subject to US income tax as the income of a resident.

The Court accepted this argument, supporting the judge at first instance in Resource Capital Fund III (RCF III). On this basis, where a limited partnership is established outside the US, it would not be a resident of the US for the purposes of the treaty even if all of its income was subject to tax in the US in the hands of the partners.

But the partners can invoke the treaty

Without expressly stating so, the plurality of the Court must have felt that this conclusion could result in practical difficulties. The judges then said that, notwithstanding the conclusions above as to the residence of the limited partnerships, US resident partners would be entitled to invoke the benefit of the treaty in recovery proceedings.

The practical effect of the Court’s decision is this:

- In the case where a limited partnership cannot establish residence in the US for the purposes of US tax (which is almost always, if not always, the case), it should not actually pay the Australian tax otherwise due.

- The Commissioner would then be forced into bringing proceedings against each of the partners to collect the tax.

- Each of the partners would then invoke the treaty in those recovery proceedings.

Clearly, we would not recommend not paying tax that has been properly assessed. However, the Court did have an alternative proposition: the partners could seek declaratory relief concerning the application of the treaty.

Each of these methods is likely to give rise to costly and time consuming litigation. This is especially so when the plurality can only comment in probabilities: “A partner would probably have standing to commence such a proceeding.” These are not very helpful observations and, even if the partners do have standing, this is not an efficient use of valuable court time.

A contrary view

We commend the sensible approach of Justice Davies in relation to the residence test. Although Her Honour largely agreed with the plurality, she disagreed in relation to the residence test. In her view, “the effect of [the relevant article in the treaty] is simply to treat partnerships as ‘resident[s] of the [US]’ if, and only ‘to the extent that’, the income derived by [the partnerships] is subject to tax in the [US] in the hands of [US] resident partners … The text indicates that the Article does not disqualify a partnership … from residency simply because [US] law does not recognise [the partnership] for [US] tax purposes.”

Commissioner is bound by his ruling

According to the Court, notwithstanding its conclusions that the limited partnerships could not invoke the US-Australia tax treaty, the Commissioner was bound by the Ruling. In that Ruling, the Commissioner in effect applies the treaty for the benefit of a limited partnership where the partners in that limited partnership are residents of the relevant treaty country (very broadly, akin to the principle that Justice Davies was seeking to apply in the interpretation of the treaty).

The Ruling is specifically in respect of the business profits article, which covers the revenue gains made by RCF. So, in a roundabout way, the Full Federal Court reached the right answer, by relying on the Ruling, the correctness of which not only they question but also the court in RCF III. This leads to the possibility, perhaps probability, that the Commissioner could withdraw the Ruling, leaving the state of the law unsatisfactory (unless of course there is special leave to appeal to the High Court).

Other principles

There are several other important principles that come from the Full Federal Court’s decisions, although we can debate about whether they are binding or guiding principles:

- Gains made by private equity type investors, such as the RCF limited partnerships (and the partners), are gains of a revenue character.

- Revenue gains made from a disposal under a scheme of arrangement conducted in Australia and with significant involvement from an Australian related party manager are sourced in Australia.

- Mining is not simply the extraction of a mineral or resource from the ground – it is the doing of all things necessary to get the resource in the desired state. This will depend on each mine and miner – the question is what is the object of the mining operations? (The Court’s analysis of this issue and the related valuation principles is a brief in itself.)

Case management

Most cases are won and lost on evidence. There is no point having evidence and leaving it in the tax files back in the office. Here are some examples from the Full Federal Court’s observations:

- No evidence as to whether the partners of the RCF limited partnerships would or did pay tax in the US.

- No evidence that the RCF limited partnerships were residents of the US for the purposes of the treaty.

- The actual mining and general leases in question were not in evidence, leaving the Court to draw conclusions based on indirect sources.

Just as important, parties should prosecute all of their legal arguments and at the right times. Failure to do so results in some unsatisfactory outcomes. Here are some examples from the Full Federal Court’s observations:

- The parties did not make considered arguments in relation to Justice Davies’ alternative construction in relation to the residency test noted above.

- The Commissioner raised the question as to whether the RCF limited partnerships were qualified persons for the purposes of the treaty, but the Commissioner had not raised it before lower court and was not a ground on the notice of appeal and so the point did not need to be considered by the Court.

- The Commissioner raised the question, in the context of the Ruling, as to whether the partners in the RCF partnerships were resident of a tax treaty country, an argument not raised in the lower court, and rejected for that reason by the Court.

- Despite calling into question the relevance of the principles in Division 855 around taxable Australian real property to the real property article in treaties, the Full Federal Court had to accept its application because both parties did not contest the lower court's application.

Where to from here

Fortunately, for the most part, the Full Federal Court’s decision means that limited partnerships can return to the way the tax world was before Justice Pagone’s decision last year.

However, there is a great deal of uncertainty that remains, not just in relation to the treatment of limited partnerships, but more general considerations by the Court, including source, real property in the context of mining, interactions between domestic law and treaties in relation to real property, and valuations.

Also open for debate is what the Commissioner will do with the Ruling, now noted as incorrect by two different courts.

Visit SmartCounsel