Small scale, large contribution

When it comes to energy, there’s a big future in small things. While Australian governments wrestle with outdated energy policies, the energy sector itself is finally moving from the industrial age to the technological age. Today, rooftop solar, and the technology and software that comes with it, promises to play a leading role in that change, with Australia well-placed to benefit from it.

Today, Australia has the highest per capita uptake of rooftop solar in the world. Rather than the state-based subsidies and feed-in tariffs prevalent in the industry in earlier years, rooftop solar now benefits from falling costs and generally rising wholesale and retail electricity prices.

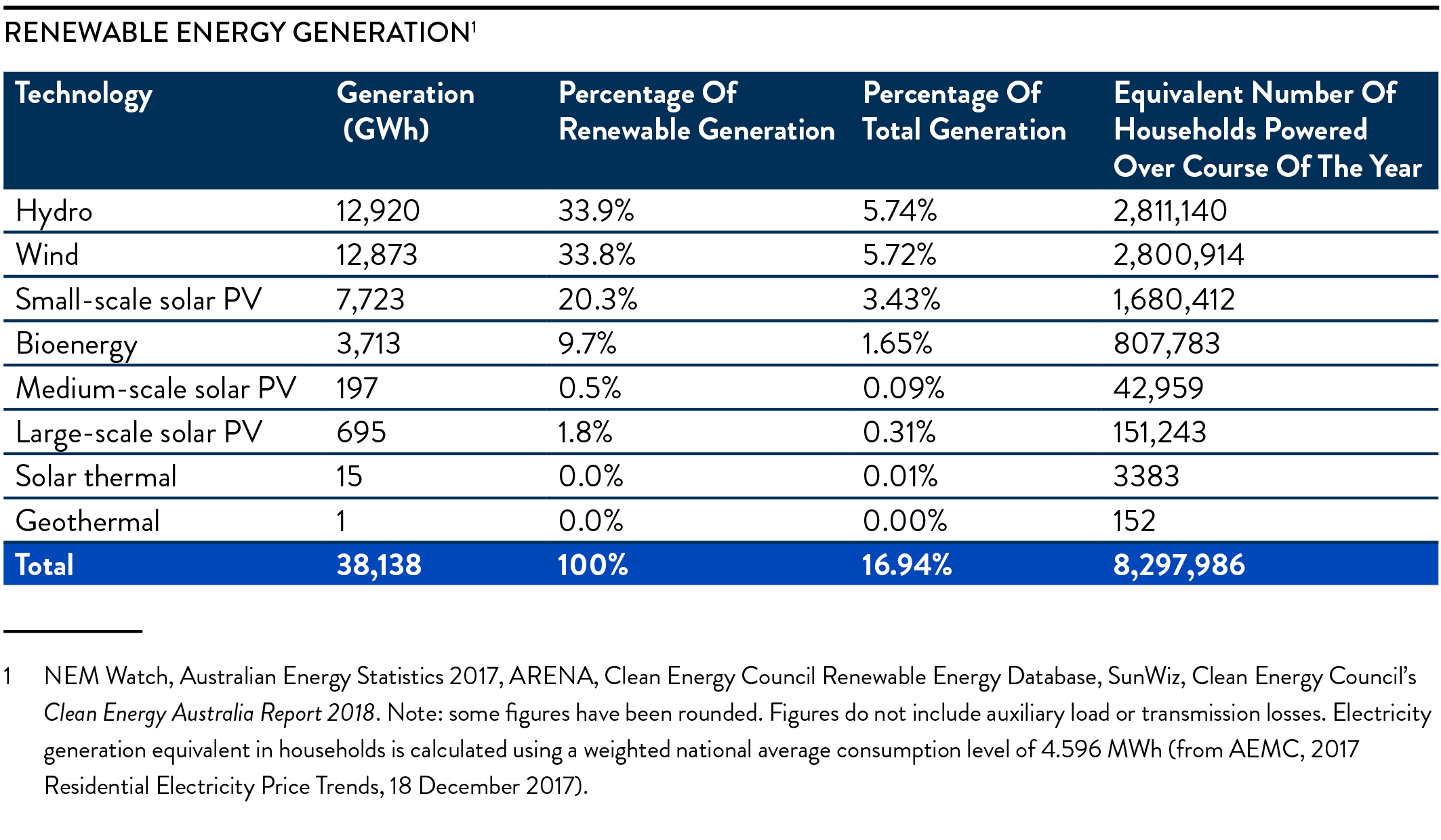

Indeed, the adoption by Australian households and businesses of rooftop solar shows no signs of abating, with almost 1.1GW of “small scale” rooftop PV (systems under 100 kW) installed in 2017, breaking the previous record set in 2012. The continued momentum of the sector led to rooftop solar generating 3.4% of Australia’s power, and 20.3% of its renewable power, in 2017, placing rooftop solar behind only hydro and wind technology in the hierarchy of renewable power generation in Australia. Notably, rooftop solar sits well above large-scale solar PV (which in 2017 generated only 0.3% of Australia’s power, and 1.8% of its renewable power – although those figures will increase as a number of large-scale solar projects that are being constructed throughout 2018 are completed).

A threat to traditional retailers, and an opportunity

A threat to traditional retailers, and an opportunity

Rooftop solar presents opportunities across the supply chain – for the manufacturers and installers who supply the kit to households and businesses, to the possibility of lower power bills for those households and businesses (as well as the opportunity to make a contribution to lowering Australia’s carbon emissions). As we consider later in this article, it also presents opportunities for those who recognise its potential in reshaping our electricity market, particularly when the rooftop solar system is combined with batteries and “smart” features, for example through a “virtual power plant” that aggregates excess power produced by a number of systems and distributes that power to other customers. While this could be perceived as a threat to the established retailers who supply power from the grid, retailers are increasingly looking for opportunities to participate in the sector through offering their own rooftop solar products to customers – enabling them to participate and develop know-how in the sector, increase their understanding of customer behaviour and usage, and adapt to a changing electricity market.

A natural fit – C&I customers and solar PPAs

A growing and increasingly competitive subset of the rooftop solar market is the increasing demand by commercial and industrial (“C&I”) customers for solar power purchase agreement (“PPA”) products. C&I customers include shopping centres, public buildings, airports and other major commercial and industrial buildings, and unlike a lot of households their demand profiles (peaking during the day) match the supply source. It has been estimated that the percentage of C&I rooftop solar buyers increased from 5% to 15% of the rooftop solar market between 2012 and 2016, and that the trend is continuing.

A PPA product involves the system-owner installing and maintaining a rooftop solar system, and the customer buying power generated by the system at an agreed price (which is typically lower than the available retailer price from the grid). As compared with alternative models, such as the outright purchase or lease of a system by the customer and ownership of all power produced by that system, solar PPAs do not require the capital outlay for a new system (which makes the model attractive to C&I customers). From the system-owner’s perspective, solar PPAs generally only make commercial sense with a larger system size and longer term (typically 10 to 15 years) – both of which are well suited to C&I customers.

Game-changing products

The increased market share, and therefore potential market power, of rooftop solar as a source of energy, and the development of complimentary products and technologies, mean that the sector is well placed to participate in the next phase of changes to the Australian electricity market. These changes are being led by (1) the increased prevalence and affordability of small scale battery storage, and (2) smart meters and plugs, which allow the electricity load used by individual appliances (for example air conditioners or hot water boilers) to be measured and controlled remotely.

By combing a solar system with a battery and load control features, the system-owner can:

- use the battery to store power produced by the system and control the timing of the later discharge of that power (including at times when the sun isn’t shining), therefore increasing the availability of the cheaper solar power and allowing the customer to consume that power at times when grid prices are high; and

- discharge power from the battery to supply controlled loads (for example to heat hot water boilers or swimming pools) at times when grid prices are high, or alternatively enable the supply of power to those controlled loads from the grid when grid prices are low.

The system-owner can also benefit from these arrangements, with more of the power that is produced by the system (including where the power is stored in the battery) being consumed and paid for by the customer, in place of power imported from the grid.

Additionally, system-owners have an eye on the opportunities that aggregation of rooftop solar systems combined with battery storage and load control features across a number of customers may present, including:

- operating a “virtual power plant” by aggregating excess power produced by individual systems that is not consumed by the relevant customer to supply additional customers under separate arrangements – expected by many to be a key feature of future energy markets and which, when combined with the use of blockchain technology, has the potential to remove centralised control of power generating assets and therefore pose a significant threat to the existing business model of traditional retailers; or

- participating on a material scale in demand response opportunities (managing power supply and demand during times of extreme peaks). This is a developing area and one of a number of mechanisms being implemented by energy regulators and the industry to maintain grid reliability – with the Australian Electricity Market Operator (AEMO) and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) having funded 10 pilot demand response projects that are expected to deliver 200 MW of capacity by 2020.

New challenges

Solar PPAs have traditionally raised a number of issues for parties to consider, for example:

- dealing with which party is responsible for grid connection and which party receives any feed-in tariffs;

- ensuring that a system-owner has sufficient access rights (particularly where the customer is not the owner of the premises);

- making sure that the fine print in a PPA complies with the Australian Consumer Law (in particular requirements relating to unfair contracts terms, which can also apply to C&I customers); and

- whether the form of the solar PPA requires the system-owner to hold an Australian credit licence under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (in particular where the PPA includes rights for the customer to buy the system at the end of the PPA term, or earlier).

However, as the new generation of rooftop systems coupled with battery storage and load control features is introduced, a new range of regulatory issues will need to be considered, including the role of a regulator in a more decentralised electricity market, and how the costs of operating, maintaining and expanding transmission and distribution networks – traditionally passed on to customers by retailers as network charges in power bills – will be funded.

At a product level, system-owners will need to navigate a number of issues including:

- parameters around when loads can be controlled by a system-owner, including how a system-owner’s load control rights interact with any competing rights that the customer’s retailer may have;

- obtaining appropriate consents from the customer to be able to use the customer’s consumption data, control the discharge of power from a battery and control consumption of power by a controlled load;

- the apportionment of liability if the exercise of load control by the system-owner results in customer loss (for example if the curtailment of controlled loads supplying air-conditioning or refrigeration on a hot day causes a business’s produce to perish); and

- whether the system-owner can deal and contract directly with a distribution network service provider, retailer or other customers (as applicable) in respect of demand response arrangements or virtual power plants.

After years of policy inertia and political fighting, Australian governments must work together to urgently formulate policy settings that accommodate both energy security and emissions reductions in a rapidly changing energy market. To date, that policy debate has been caught in a zero sum game between thermal “baseload” power and utility scale renewable energy developments. No doubt both of these utility scale sectors will have an important role to play, but at the intersection of households, businesses, rooftops, software, storage and solar lies a growing piece of the puzzle. It will be important that it is not ignored.

Visit SmartCounsel