The final report of the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (the Commission) is compulsory reading for senior management in the banking, superannuation, insurance and related (financial services) industries. But is there a tax angle?

Reading the Commission’s final report to determine its broader application is a bit like reading Shakespeare and trying to discern the meaning and intent of words written more than 400 years ago. Justice Hayne would chastise us for taking the report out of context and well beyond its terms of reference. Yet, a royal commission does not happen every day and valuable life lessons can be learnt by watching others falter.

This four-part series looks at the impact of the Commission’s findings and recommendations, some lessons from those findings and recommendations and how they may apply equally to tax professionals inside and outside the financial services industries (if you like, the hypothetical findings and recommendations of a royal commission into the tax industry!). We look at:

This series does not look at the findings and recommendations of the Commission more generally. Instead, Gilbert + Tobin’s Disputes + Investigations team has prepared a separate review of the Commission’s findings.

Part One: tax law

The Government has agreed to implement all of the Commission’s 76 recommendations, including those relating to the simplification of the law. There are other lessons that both the Government and the ATO can heed from the Commission’s final report.

Key takeaways and action items

- The tax law should be simplified, with a particular focus on exceptions, concessions and opportunities for categorisation. Despite the failings of the purposive approach to drafting, the purpose and objectives of the law should be clear and should be more than just statements – they should be enforceable operative provisions.

- The ATO and the Tax Practitioners Board (TPB) can be expected to maintain a high profile in the enforcement of their respective law.

- The ATO should take heed of the Commission’s recommendations on its dealings with distressed tax debts and more broadly in relation to its dealings with taxpayers.

- There are implications for tax practitioners, which we will look at in Part Three of this series

Simplification

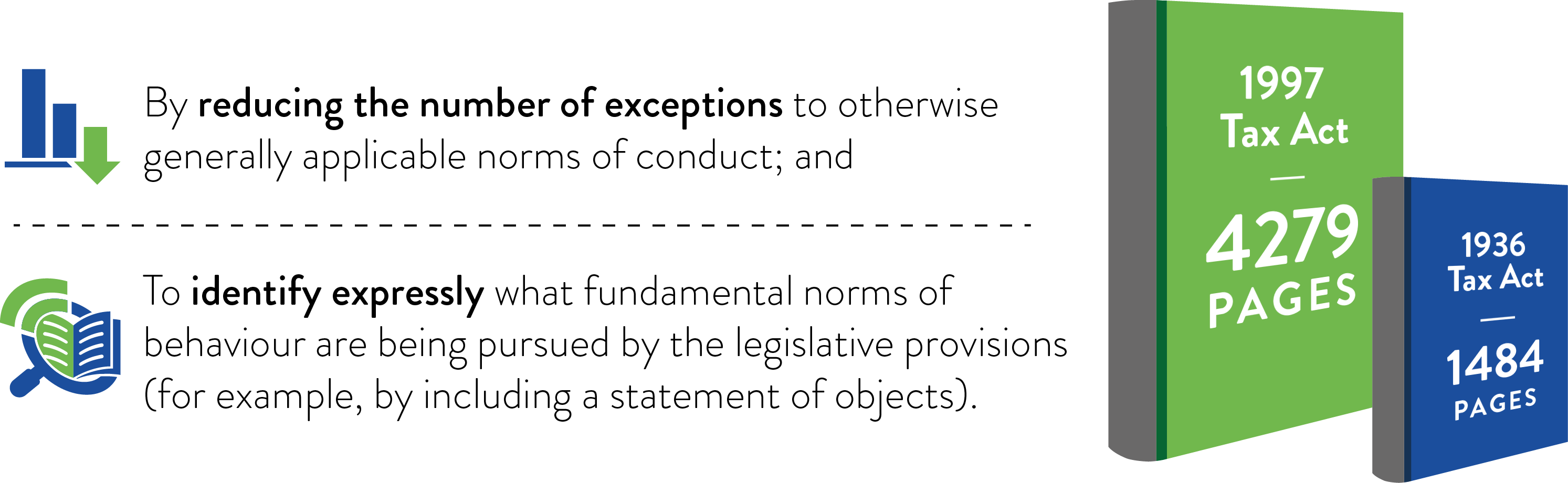

A key recommendation of the Commission is the simplification of the law through two key strategies:

The Commission notes that the “more complicated the law, the harder it is to see unifying and informing principles and purposes”and that an important effect of the complexity of the law is that entities meet the terms of the law (that is, a focus on literal application), rather than its intent. The focus on literal application results in more uncertainty and “boundary-marking and categorisation”.

Nowhere is this more true than in the tax law – as tax law is introduced, taxpayers and tax advisers alike work to understand the limits of the tax law and comply with the express words of the law. A recent example is that no sooner had the anti-hybrid measures been introduced than the ATO expressed concerns at the schemes that skirt around those provisions. The categorisation of taxpayers into different types of entities with nuanced rules, the classification of gains into revenue and capital with markedly different tax treatment and a vast array of exceptions and concessions (with exceptions to those exceptions and concessions) are further examples of substantive complexity.

A contrary view is that, unlike the consumer protection bias of the law that the Commission was examining, the tax law is aimed at generating and protecting the revenue of the Government, and therefore it does need to be complex. However, this misses the Commission’s point – its observations are not merely about complexity but about unnecessary complexity, and complexity is not always needed to achieve the intended objectives. The Commission’s ideal example of simply understood precepts, such as “misleading or deceptive conduct”, may never come to fruition in the context of tax law or the extremely complex arrangements that drive significant tax outcomes, but as the Commission notes, “the very size of the task [of simplification] shows why it must be tackled”.

It is incredible to think that we have now had two income tax acts for 22 years, with minimal effort to fold one into the other in that time. What is worse is that we have current law that relies on repealed law for effect, law that relies on concepts that are impossible for professionals to describe and taxpayers to comprehend and law that taxpayers are expected to comply with that has been announced but not even drafted let alone enacted.

Be seen to be enforcing

A key message of the Commission is that it is important for regulators to be seen to be acting in the supervisory capacity in order for there to be trust in the regulators. It appears that the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, in particular, would take remedial action, rather than enforcement action.

There is no doubt that the ATO is extremely active in enforcement, and that such enforcement is public. Recent examples include a prosecution for fraud,a notable settlement on marketing hubs and regular appearance before tribunals and courts on points of law arising from audit activity. And every taxpayer is aware of the range of reviews and audits that can be and are undertaken by the ATO, including regular review programs such as the Top 1,000 Tax Performance Program, and the ever looming threat of such reviews and audits. The ATO’s media presence is notable, as is its presence before Parliamentary committees.

The other regulator in the tax industry is the TPB. It too is generally seen to be active in enforcement against tax practitioners. However, the number of practitioners who are delinquent in their own personal tax affairs (in breach of the code of conduct and the Tax Agents Services Act 2009 (Cth) (TASA)) means the TPB currently focuses on significant misconduct, such as fraud.

A taxpayer-centric approach to debt collection

This is one area where, clearly, we are taking some poetic licence of the Commission’s final report. However, having seen the ATO’s approach to debt collection first hand and recent negative publicity of the ATO’s heavy handedness, the ATO may well pay heed to the Commission’s observations.

The Commission made some recommendations about the banks’ approach to debt collection of distressed agricultural loans. Those observations and recommendations are aimed at two important and beneficial objects – to keep the farms afloat and to get the debts repaid. These objects should equally apply to any tax debt owed to the ATO (not just those of farms) – keeping taxpayers afloat ensures the ability to collect more tax in the future, and getting the tax debts repaid ensures more tax is collected today.

Some observations of general application include:

![ The ATO should have regard to the underlying circumstances giving rise to the inability to satisfy tax debts. The ATO is generally quick to provide relief to taxpayers and tax advisers affected by natural disasters but the Commission does note that “[n]atural disasters are not the only reason [a] loan may become distressed”. The ATO should offer mediation to seek agreement about how to work or trade out of any existing and reasonably anticipated financial distress. The ATO should manage every distressed debt on the footing that working out of distress will be the best outcome for the ATO (and the public) and the taxpayer, and recognise that the appointment of receivers and other external administrators is a remedy of last resort. From our experience, this is particularly true – often, the threat of liquidation is a stick brandished about by the ATO following amendments made after an audit despite the resolve of taxpayers to work through the distress and pay their tax debts. The ATO should cease charging default interest (which, arguably, is akin to the shortfall and general interest charges to the extent above commercially available rates) where there is no realistic prospect of recovering the amount. The ATO cannot do this unilaterally except through remission of interest – statutory changes are necessary.](https://cdn.brandfolder.io/3RTTK3BV/as/pnxddh-c93y8o-cpz60w/TaxAngle.png?position=3)

Impact of compensation payments and other adjustments

In Part Two of this series, we highlight some of the implications that can arise from compensation payments and other adjustments that could occur as a result of the Commission’s work. Given the potential complex tax implications, one would hope the ATO would take a concessional and sensible approach to the tax treatment of those payments and adjustments. Some public guidance from the ATO on their likely approach would also be welcome.

Visit SmartCounsel