What has happened?

On 5 December 2018, the second last parliamentary sitting day of the year, the Federal Government introduced the Treasury Laws Amendment (Prohibiting Energy Market Misconduct) Bill 2018 (the Bill), which aims to implement the Government’s so-called ‘big stick’ energy reforms.

The Parliament ultimately ran out of time to debate the bill (given debate over immigration amendments proposed by the crossbench) and so the Bill will be debated when, or if, Parliament returns in 2019. The Bill has also been referred to a Senate Economics Committee by Labor which is likely to result in further delay.

The Bill is extraordinary and has been roundly criticised by industry groups and others across the energy sector. If passed, the legislation would add three new electricity sector-specific prohibitions to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) and confer on the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), the Treasurer and the courts a suite of tools to tackle non-compliance.

The fundamental problems with the Bill are:

1. The unclear nature of the prohibitions, combined with potentially drastic penalties, add an additional degree of regulatory uncertainty to a sector that is already suffering from a lack of certainty and policy direction.

2. This regulatory uncertainty will deter needed investment in the sector, making it increasingly difficult for investors to make investments that could drive down prices.

3. The draft laws were not recommended by the ACCC following its recent, comprehensive, electricity inquiry but are a rushed, piecemeal reaction by the Federal Government to public concerns about electricity prices. The wide reaching and long-term consequences of these proposed laws demand extensive, considered and rigorous consultation which has not been undertaken.

In its current form, the Bill will not lead to lower prices or restore public confidence in the electricity sector, it is more likely to have the opposite effect. The Bill represents a further unfortunate and politicised development in Australian competition policy, reminiscent of other CCA developments such as the ‘Birdsville pub’ amendments to section 46 in 2007, and the misconceived price signalling provisions aimed at banks in 2011, subsequently removed by the Harper Review.

There is also a risk that politicised and draconian remedies of this kind may be viewed as appropriate in other contexts in the future – undermining the integrity of Australian competition law.

Below we provide a brief outline of the proposed prohibitions and some of their potential effects.

Prohibitions

1.1 Prohibited Conduct in relation to retail pricing

The reforms introduce a vague new provision, which is directed at forcing electricity retailers to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to retail prices in response to ‘sustained and substantial’ cost reductions.

An electricity supplier would contravene this provision if it:

- offers to supply, or actually supplies, electricity to small customers; and

- fails to make reasonable adjustments to its price to reflect sustained and substantial reductions in its underlying cost of procuring that electricity.

This is a wholly unprecedented prohibition in an Australian legal context, in electricity or any other sector, and has (at least) two critical flaws:

- It is unclear what needs to be done to comply with the draft law. Key phrases– ‘reasonable adjustments’, ‘sustained and substantial’, and ‘underlying cost’ – are left undefined and remain inherently uncertain, particularly in a market which is as complex and multi-faceted as energy markets. This creates the real and ongoing compliance risk of retailers facing pricing decisions that are second guessed by a regulator after the event.

- The Bill weakens incentives for retailers to pursue cost-saving initiatives as any ‘sustained and substantial’ cost reductions that are achieved must be wholly passed on to consumers. Investments in cost reduction and efficiencies are often associated with risk and uncertainty, and if they are successful then companies face the prospect of having to adjust prices to reflect their lower costs. This creates a perverse disincentive against pursuing such initiatives, which may ultimately lead to a less efficient electricity supply sector and higher prices.

The Government appears to be alive to the second of these concerns, because the explanatory memorandum for the Bill states that:

Where a retailer is able to lower its operating costs, for example by improving its internal processes and becoming more productive, retailers would typically use the resulting savings in the short run to achieve a combination of becoming more price-competitive and benefiting their retail margin. The legislation does not require a retailer to adjust its prices to pass through such efficiency gains, as the legislation is primarily concerned with broad, market-wide price trends. The ability to benefit from efficiency gains is the retailer’s financial incentive to identify improvements, p 20.

Unfortunately, the statement that the legislation is ‘primarily concerned with broad, market-wide price trends’ is not explicitly reflected anywhere in the legislation. This is an example of how the rushed process to implement these laws means that it is not clear that the drafting ultimately achieves the Government’s policy intent.

1.2 Prohibited conduct in relation to electricity financial contracts

This prohibition is directed at vertically integrated ‘gentailers’, and places additional regulation on supply of electricity financial contracts. These contracts allow retailers to effectively fix a price for a specified quantity of electricity, providing retailers certainty about future electricity prices.

A corporation contravenes the law if it:

- is a corporation that generates electricity, either itself or within its corporate group;

- fails to offer to enter into electricity financial contracts, limits or restricts offers to enter into electricity financial contracts, or offers to enter into electricity financial contracts in a way that has the effect of limiting or restricting acceptance of those offers; and

- does so for the purpose of substantially lessening competition in any electricity market.

The objective of this draft prohibition is to ensure ‘generators, including gentailers, do not unreasonably refuse to offer financial contracts for anti-competitive purposes’.

This appears to be a prohibition in search of a problem. In its recent Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry Final Report, the ACCC made no finding that generators were refusing to offer financial contracts for anti-competitive purposes, and there has been no public allegation of that kind of conduct in the sector.

1.3 Prohibited conduct in the wholesale electricity market

There are two draft prohibitions directed at conduct in the electricity wholesale market.

A corporation contravenes the law if:

- It bids or offers to supply electricity on an electricity spot market; or fails to bid or offer to supply electricity on such a market; and

- Either (in the case of the ‘basic’ case) or both (in the case of the ‘aggravated’ case) of the following is made out:

- the corporation has acted fraudulently, dishonestly or in bad faith in carrying out the behaviour; or/and

- the behaviour has been carried out for the purpose of distorting or manipulating prices in the electricity spot market.

There has been considerable recent debate about the health of the National Energy Market (NEM) and whether it is subject to market manipulation by large participants. The issue was the subject of detailed review resulting in reforms to the National Energy Rules (NER) to introduce a new good faith rebidding rule in 2015.

In its recent report into the retail electricity market the ACCC found that ‘clear instances of manipulation are not a major feature in the market today’ and only recommended a new rule in the context of the stronger links between wholesale and contract markets that were envisioned under the draft design of the National Energy Guarantee (NEG), which is now abandoned.

In contrast, in July 2018, the Grattan Institute released a highly publicised report that claimed that ‘gaming’ by generators had contributed approximately $800m to wholesale electricity costs – mostly in Queensland. The Grattan analysis was reviewed by the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) at the direction of the Minister and was largely discredited. The AEMC final report, published in September 2018, showed that price spikes in the NEM associated with rebidding by generators accounted for only 1% of the wholesale cost of energy in the NEM in 2017 and was unlikely to have been passed through to consumers. The AEMC found there was certainly no case for major concern or reform of rebidding rules.

Yet again, the market manipulation amendments are a poorly framed solution looking for a problem and, moreover, in direct conflict with the best and most recent advice from the Government’s independent market regulators (ACCC and AEMC).

The explanatory memorandum suggests that the Bill is seeking to prohibit conduct that ‘seeks to undermine the process by which market participants would reasonably expect prices to be determined in a market characterised by effective competition’, which is far from a clear standard of conduct. The explanatory memorandum also recognises that ‘transitory market power can be an acceptable feature of an electricity spot market because it can create a signal for investors to invest in new generation when and where it is needed by the system’ but the laws make no explicit allowance for this important feature of the market, aggravating the lack of clarity as to what is and is not permitted.

Remedies

One of the most concerning aspects of the new laws are the consequences that may be faced following a contravention, or in some cases a mere ‘reasonable belief’ by the ACCC and the Treasurer of a contravention.

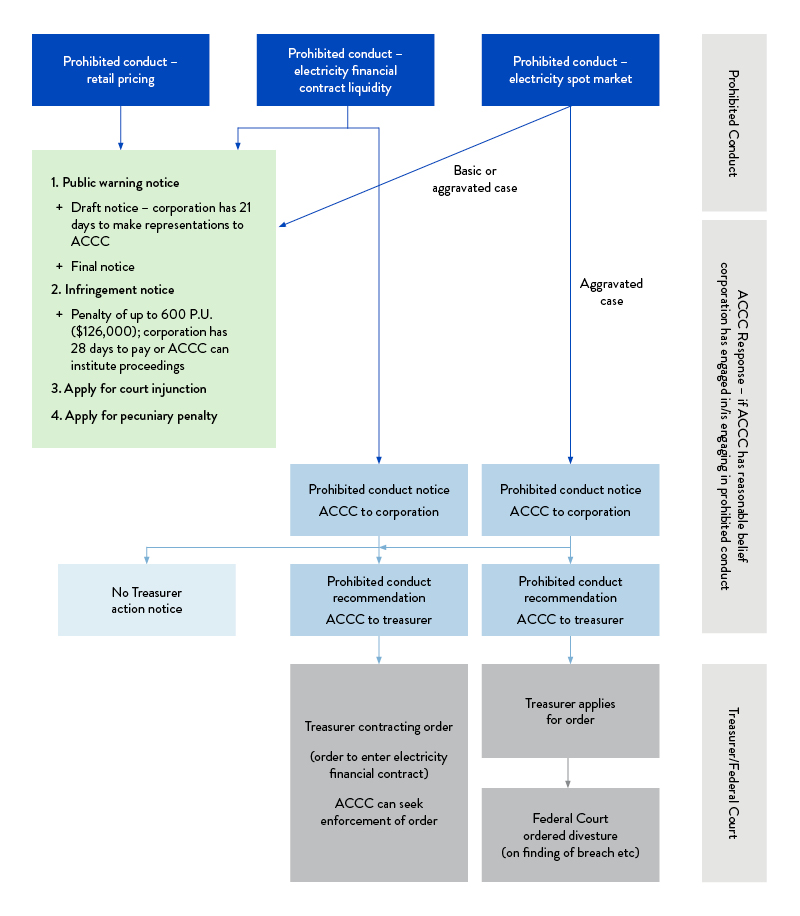

The possible range of remedies, and which remedies relate to which prohibition, is summarised in the diagram below.

This is a broad and unprecedented suite of remedies in the CCA. The proposed contracting order can be imposed by the Treasurer without any proof of a prohibition by a court, and result in a company having to commit to supplying such contracts on terms specified by the Minister.

While the ‘big stick’ divestiture power has been watered down somewhat from earlier drafts, the threat of divestiture is an extreme and draconian outcome. It will add to investor risk and uncertainty in an already risky and uncertain sector, particularly coupled with the lack of clarity in the underlying prohibitions. The ACCC explicitly rejected introduction of divestiture powers in its recent report, and the Government has provided no good reason why they are required.

AER information gathering powers

The Bill also introduces new compulsory information gathering powers on the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) and allows the AER to disclose information with other agencies, if it requires information gathering or information disclosure for the performance of its Commonwealth functions.

Conclusion

There is an existing rule-making, consultation and decision-making framework in the NEM for good reason – the sector is complex, and rules can have unintended and unforeseen consequences.

Moreover, the Government’s proposed reforms are directly inconsistent, in a number of respects, with the best and most recent advice of the AEMC and ACCC.

Unfortunately, the Bill reflects a rushed attempt to implement confusing and ill-considered laws. Given that the bill has been referred to a Senate committee, with a report due on 18 March 2019, it seems almost impossible for it to be passed before the next election.

A link to the Bill and the explanatory memorandum can be found here.

Visit SmartCounsel