In a recent update “Embedding ESG factors into mainstream investing” some of our colleagues discussed ESG (environmental, social and governance) concerns finally coming out of the shadows and becoming genuine considerations in investment decision-making. Appreciation of ESG has gone mainstream, with our colleagues citing $USD59 trillion in assets now invested in accordance with the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (which are based on ESG factors). Half of the top 100 Australian Super funds (some of our most influential investors in Australia’s capital markets) have now signed up to the UN PRI principles.

The article notes that most financial organisations now have ESG policies and evaluation tools and that there is an exploding number of frameworks being produced by credit agencies and third party financial groups to facilitate ESG reporting and scrutiny.

But how sticky is this stuff really? How committed are companies and their Boards to meeting targets driven by hard-to-prove future benefits when the going gets tough? Do we actually empower the brave souls leading in the area to hang in there when the pressure comes from short term investors whose investment strategies are often openly hostile to ESG concerns?

Good Intentions Fade

The article cited a widely used definition of the notoriously malleable and nebulous concept of ESG being “non-financial performance indicators which include sustainable, ethical and corporate governance issues such as managing the company’s carbon footprint and ensuring there are systems in place to ensure accountability.”

We’ve talked a lot on this blog about the growing mood to consider an expanded universe of stakeholder interests - employees, communities and society generally - but for the purposes of this article we’re going to talk about the “E” in ESG (because it’s the best example of how thorny things get for directors under Australia’s corporate governance rules).

In a fantastic piece “Why we can’t rely on corporations to save us from climate change” Christopher Wright (Professor of Organisational Studies, University of Sydney) and Daniel Nyberg (Professor of Management, University of Newcastle) describe the findings from some remarkable research (which conveniently support a favourite theme of this blog) – that ambitious long term proposals (in this case pro-climate initiatives) become “systematically degraded” by criticism from shareholders and other market participants.

In summarising how the best intentions of big business die in the trenches of short termism, the authors find:

“This “market critique” reveals the underlying tension between the demands of tackling climate change, and the more basic business imperatives of profit and shareholder value. Managers operate within increasingly short time frames and demanding performance metrics, due to quarterly and semi-annual reporting, and the shrinking tenure of executives.”

Sound familiar?

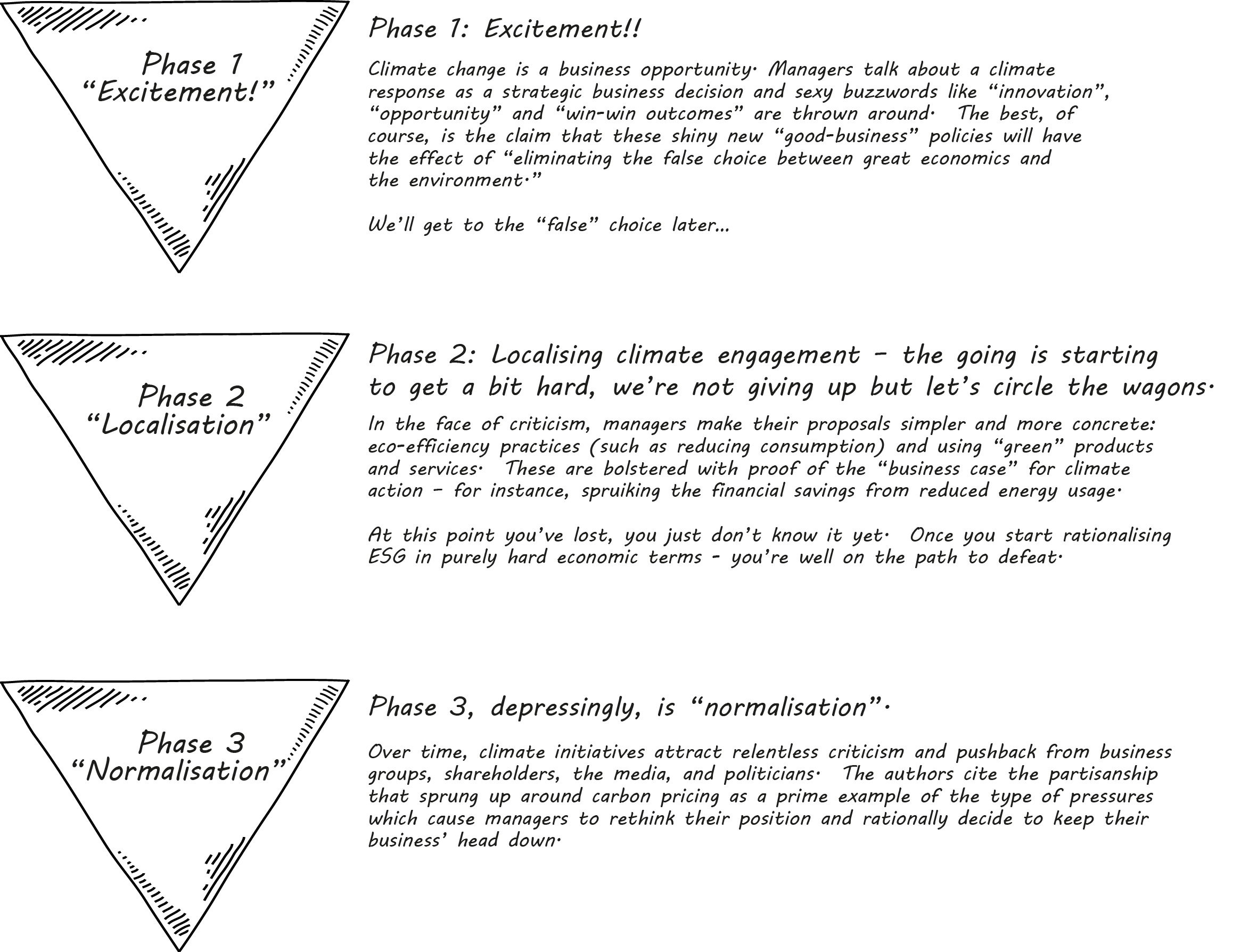

Their research described the process of corporate leadership in climate change following a descending path with three distinct phases:

A perfect recent ESG example was Peter Dutton’s now famous criticism of Alan Joyce on the SSM debate. Let’s imagine for a second that an airline’s management, rather than engaging in social advocacy, announced it was only going to use the most eco-friendly jet fuel, driving up their annual energy costs by 50% because it was the right thing to do for the environment. Criticism by government and the market would be even harder to resist because, unlike social activism, this type of environmentally responsible action would involve incurring real and immediate financial costs with no foreseeable economic payoff in sight. So when their big shareholders came knocking and said “stick to your knitting” they would be very hard to ignore.

Ultimately Wright and Nyberg found that climate change initiatives were wound back, market concerns prioritised and “the temporary compromise between market and social/environmental discourses was broken and corporate executives sought to realign climate initiatives with the goal of maximising shareholder value.”

The key takeaway – our corporate governance regime simply does not allow environmental entrepreneurialism. We cannot pretend that wholeheartedly addressing environmental concerns sits perfectly with a duty of profit maximisation – it doesn’t and it can’t. That is a false abstraction of a genuine choice that needs to be made: the choice between short-term profit maximisation and responsible long-term environmental stewardship. Directors will make their choice, and in the absence of express statutory protections, they will act in short-term shareholder interest – because they have to. The choice faced is real, you’re just only allowed to choose option (a). As concluded by Wright and Nyberg:

“Businesses operate on short-term objectives of profit maximisation and shareholder return. But avoiding dangerous climate change requires the radical decarbonisation of energy, transportation and manufacturing on a scale that is historically unprecedented and probably incompatible with economic growth.

This means going beyond the comfortable assumptions of corporate self-regulation and “market solutions”, and instead accepting regulatory restrictions on carbon emissions and fossil fuel extraction.

It also requires a reconsideration of corporate purpose and the dominance of short-term shareholder value as the pre-eminent criteria in assessing business performance. Alternative models of corporate governance, such as B corporations, offer pathways that better acknowledge environmental and social concerns.”

Yes. This. The current rules need to change to allow a “choice”.

New Structures for New Outcomes

The reference above to “B corporations” leads to another FWD hobby horse (maybe a dead one we keep flogging) – the benefit corporation. You can’t change behaviours without changing the rules that drive the behaviours. The benefit corporation is a different corporate structure, with different rules.

As we set out in “How a new corporate vehicle could save Australian media”, the U.S. has the concept of a “benefit corporation” as their “for-profit and purpose” vehicle (whilst the U.K. have the community interest company). The precise formulation of what is a benefit corporation differs from state to state, but broadly, the concept is to value the collective good, with directors legally obliged to pursue a public benefit alongside profit (with this public benefit originally envisaged to centre on environmental benefits). This is achieved by framing the generation of a public benefit as being in the best interests of the benefit corporation – broadening the corporate mission and with it the fiduciary duties. In order to act in the “best interests of the company”, amongst other things, directors are compelled to advance the defined public benefit. Put simply, benefit corporations are mandated by law to consider their overall impact on society, their workers, local communities and the environment, in addition to the goal of maximising shareholder profit.

Some of the key features of the benefit corporation (from a range of legislative regimes):

- Incorporated for profit and purpose: A benefit corporation is required to pursue profit and a general or specific public benefit.

- Duty to act in the best interest of the benefit corporation: Embedded in this duty, directors are compelled to advance the specified public benefit.

- Standing to bring an action: A defined class of persons (eg, the shareholders, the other directors or a regulatory body) is given standing to bring an action for an alleged breach by a director of the expanded duty.

- Benefit report: Requirements to prepare and publish a “Benefit Report” providing sufficient information to investors and the public regarding the pursuit of the defined public benefit.

- Third party standards: Requirements for “Benefit Reports” to be prepared/certified in accordance with 3rd party standards to ensure credibility and consistency in reporting.

You could see that in a benefit corporation it would be much easier for directors to avoid slipping from Wright and Nyberg’s hopeful phase 1 (“Excitement!!”) into the depressing functionalism of Phase 3 (“Back to Normal”).

Another highly recommended article by Martin Lipton and co. on trends in the U.S. describes benefit corporations as part of the metastasisation of the debate over the value purportedly created for shareholders by activists vs the common sense notion that boards should have a fiduciary duty not just to shareholders, but also to employees, customers and the community. It is this “constituency theory of governance” that is driving the benefit corporation concept.

Importantly, Lipton and co. call out the real consequences of the shareholder primacy model taken to its extremes:

“Despite the developments and initiatives striving to protect and promote long-term investment, the most dangerous threat to long-term economic prosperity has continued to surge in the past year. There has been a significant increase in activism activity in countries around the world and no slowdown in the United States. The headlines of 2017 were filled with activists who do not fit the description of good stewards of the long-term interests of the corporation… As long as activism remains a serious threat, the economy will continue to experience the negative externalities of this approach to investing – companies attempting to avoid an activist attack are increasingly managed for the short term, cutting important spending on research and development and focusing on short term profits by effecting share buybacks and paying dividends at the expense of investing in a strategy for long-term growth”

So why, despite a growing commitment to at least superficially consider and measure ESG factors, are we still here? Why are things actually getting worse?

As we said in our recent article on executive remuneration:

“..moving to more long-term company decision making isn’t just a question of values, it’s also a question of law. The Corporations Act requires directors act in good faith in the best interests of the company. This is the foundation stone of directors’ duties in this country. While some academics argue that ‘interests of the company’ includes those of future shareholders and even the community, the approach of Australian courts has been to treat shareholder value as the be-all-and-end-all. This widely accepted reading of directors’ duties – where protecting and generating value is all that matters – could mean directors are breaching their duties (and exposing themselves to penalty) if they focus on anything other than returns for current shareholders.

Essentially, devoting company resources to long-term or non-financial factors (or voluntarily airing laundry by disclosing non-compulsory metrics) could actually be a breach of duty. A UN environmental initiative has acknowledged this issue. In a recent report, it asked APRA to clarify whether fiduciary duties in Australia require attention to be paid to long-term factors in decision making, and for all relevant Australian regulators to clarify that responsible investment includes environmental, social and governance integration and policy engagement, regardless of the effect on shareholder value. The only reason those types of assurances would be needed is because that’s not the law as it currently stands!”

So for now, Australian directors can only take real ESG action (and stick to it when pressured) if they successfully make the argument that it is in the interests of the companies they serve – not hard to prove with, say, long-term focused executive remuneration practices – very hard to prove with voluntary environmental disclosures and “elective” and expensive environmental programs.

Empirical evidence shows that this sentiment has been felt by directors for years. A 2012 paper analysing survey results of directors of leading Australian companies showed a widespread belief amongst directors that their paramount duty is to shareholders. By comparison, collectively, only 5.4% of directors included “The Environment” or “The Community” in any of their top 3 priorities.

As we said in “Goliath Primacy and the Director’s Dilemma”, short-term focused institutional shareholders have the means to pressure directors and, frankly, are more likely to sue for perceived breaches of duty. This “Goliath” shareholder primacy in practice means the noisiest and most powerful shareholders are very hard to resist when they apply pressure for short-term decision making (such as demanding capital returns or cost cutting) at the expense of environmental action that pays no immediate dividends.

The US is seeing prominent investors banding together to develop governance frameworks to combat short-termism, whilst just this week the Climate Action 100+ initiative was launched by 200 investors (with collectively US$26 trillion in assets) with a mandate to force corporate action by the world’s 100 biggest polluting companies. But we can’t rely on shareholders always supporting ESG initiatives. As long as the rules of the game are as they are, the mere threat of a lone self-serving goliath is all it takes to deter Boards from fully embracing ESG practices. Until directors have a legal defence against Goliath Primacy, they will keep doing what they have to do.

Visit SmartCounsel