The Bank of England (BoE) recently released a discussion paper on AI financial regulation, accompanied by its second annual survey of use of machine learning (ML) in the UK financial sector.

How and where is AI being used in the financial sector

Unsurprisingly, the BoE survey found an accelerating use of ML by financial firms.

Overall, 72% of firms that responded to the survey reported using or developing ML applications compared to 67% in the 2019 survey. The overall median number of ML applications is expected to increase by over 3.5 times over the next three years, with the largest expected increase is in the insurance sector.

More interesting are some of the underlying trends.

First, there has been a substantial shift in ML from the development stage to the deployment stage. 79% of ML apps were in deployment, with only 10% in development stages, which compared to 44% in development stage in the 2019 survey. The BoE concludes that “[t]his suggests the survey respondents’ ML applications are more advanced and increasingly embedded in day-to-day operations.”

Second, the non-bank lenders are much more ambitious in their use of ML. Non-bank lenders have the highest percentage of ML applications (42%) that are critical to business areas compared to less than 15% with banks.

Third, while most ML are used in ‘customer engagement’ (28%) and ‘risk management’ (23%), there appear to be big shifts in the pipeline. While current use of ML in treasury (0.4%) and investment banking (0.9%) is very low, the areas with the highest proportion of ML applications at the pre-development stages are treasury (40%) and investment banking (58%). Of treasury ML apps deployed and under development, 40% were described as critical to business – the highest of area business or functional area.

The most commonly cited current uses of ML were as an input to compliance: money laundering (AML) and customer ID’ing (KYC). While many ML apps appeared to translate existing risk assessment models to an ML environment, the BoE also highlighted some more innovative use cases:

- telematics risk modelling based on Deep Neural Networks to estimate driver behaviour and, thereby, predict the magnitude of the claim and determine the premiums charged to the consumer.

- A ML model in the early stages of operation predicts the probability of the applicant entering significant arrears in the first 12 months of the loan being opened.

Fourth, the BoE survey found an increasing level of internal ML app development by financial firms: 83% of respondents develop and implement ML applications internally compared to with the 76% in the 2019 survey. But the BoE cautioned that:

“..the line between ‘internal’ and ‘external’ implementation is becoming increasingly blurred. This is because ML systems are becoming more complex and rely on a mix of internal and external components (data inputs, ML models, software packages, cloud computing storage, etc). For example, firms may develop models and code algorithms internally but use third-party data sets or base their algorithms on third-party cloud computing platforms.”

Future regulation

The purpose of the BoE’s discussion paper is to canvass the adequacy of the current UK financial markets regulatory framework in addressing AI.

The BoE discussion paper focuses on so-called “cross cutting” issues across all financial sectors that carry multiple areas of risk:

- Data-related legal requirements and guidance are targeted at data quality, data privacy, data infrastructure, and data governance.

- Model-related legal requirements and guidance for managing capital risks may provide safeguards surrounding the model development, validation, and review processes for the firms to which these apply.

- Governance-related legal requirements and guidance are focused on proper procedures, clear accountability, and effective risk management across the AI lifecycle at various levels of operations.

Importance of defining AI

The BoE discussion paper notes that, as there is likely to be an increasing level of AI-specific requirements (whatever the regulatory model is), an important threshold issue is to work out how to distinguish between AI and non-AI. The discussion paper identified two approaches:

- providing a more precise legal definition of what AI is (for example, the definition of ‘artificial intelligence system’, and thereby what AI is not (e.g. the Canadian AI and Data Act); or

- viewing AI as part of a wider spectrum of analytical techniques with a range of elements and characteristics, which may include a classification scheme to encompass different methodologies or a mapping of the characteristics of AI (the German approach to financial services regulation).

The BoE seems inclined to the first approach because of the benefits in (i) creating a common language for firms and regulators, which may ease uncertainty; (ii) assisting in a uniform and harmonised response from regulators towards AI; and (iii) providing a basis for identifying whether or not specific use cases might be captured under particular rules and principles.

But the BoE also recognised that any attempt at a precise definition may become quickly out of date with technological advances or in the effort to avoid that risk, become so generalised that it defeats the objective of having a more precise definition in the first place.

Benefits and risks

The BoE discussion paper has a fairly standard, if not anodyne discussion of the benefits and risks of AI in the financial sector, but makes a couple of interesting points:

- AI’s capacity to adapt continuously makes system more susceptible to ‘data drift’ and ‘concept drift’, which in can in turn make the models and systems less stable. The potential for drift, combined with the lack of explainability inherent in increasingly complex AI models, can in turn lead to a range of prudential risks. For example, the use of complex and/or opaque AI systems to model probability of default and loss given default in credit models could lead to firms having incorrect levels of regulatory capital.

- In insurance, AI models trained on historical data may not account for a breakthrough healthcare treatment, which can lead to mispriced policies.

- the use of similar datasets and AI algorithms may result in uniformity across models and approaches at multiple firms, which could amplify procyclical behaviour and lead to herding in trading.

- markets could also potentially become vulnerable to manipulation and prone to flash bubbles or crashes if sentiment analysis and social media signals were used at scale in AI trading.

Regulatory models

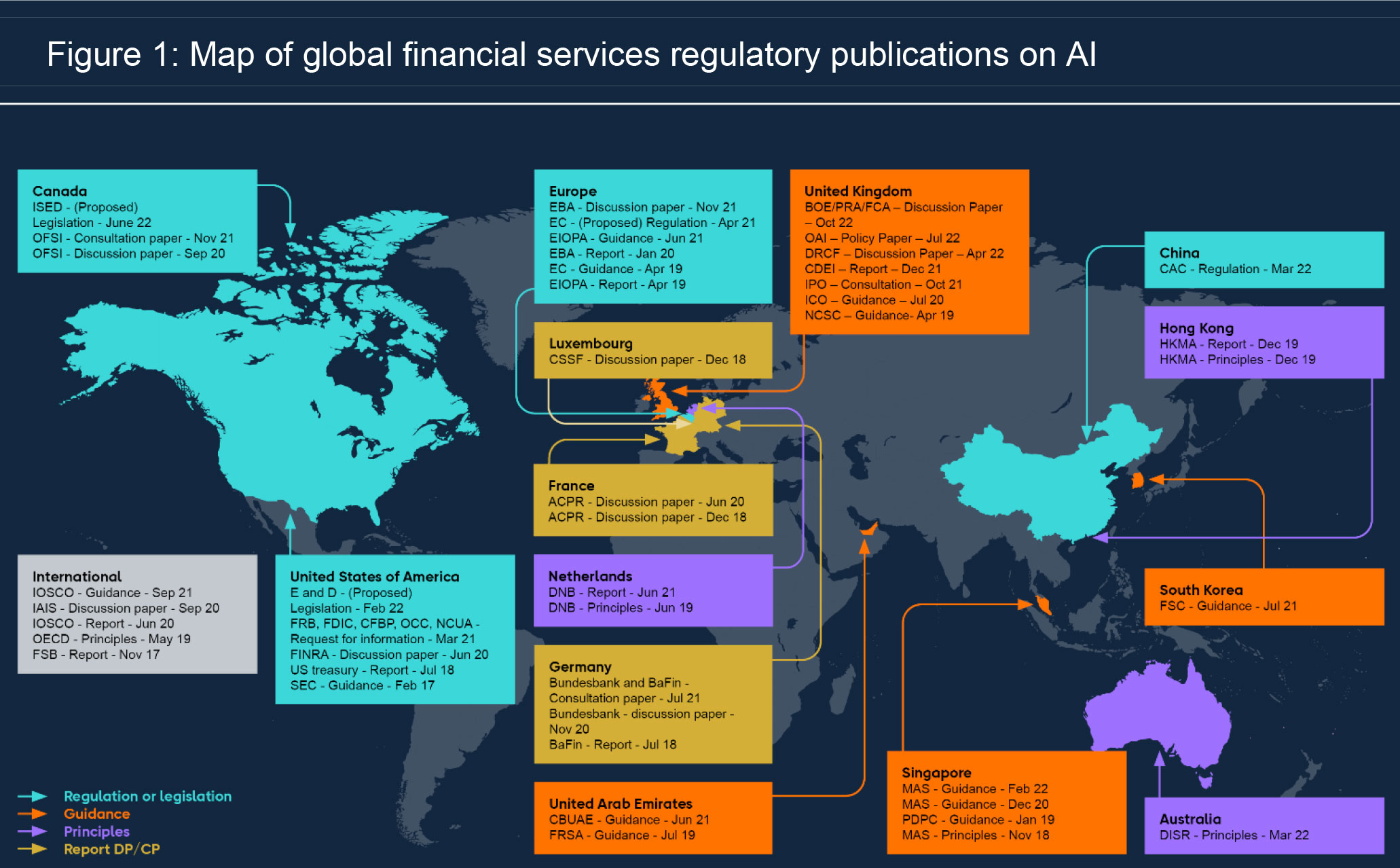

The BoE frames the central issue to be resolved as being “whether [AI] can be managed through extensions of existing regulatory frameworks, or whether a new approach is needed.” The BoE notes, as illustrated in the following handy graphic, that regulators around the world are grappling with this question with different outcomes:

The BoE discussion paper itself never really comes to grips with this central question, but descends into cataloguing of the current UK regulatory measures and guidance. However, the BoE discussion paper makes the following useful points.

The UK financial services regulator, the FCA, has introduced a new Consumer Duty which requires “firms to play a greater and more positive role in delivering good outcomes for consumers, including (where a firm can determine or materially influence outcomes) those who are not direct customers of the firm.” The BoE gave the following example of how the Consumer Duty could apply to AI:

“The Consumer Duty does not prevent firms from adopting business models with different pricing by groups (for instance risk-based pricing), but firms would need to ensure the price charged is reasonable, relative to the expected benefits (i.e. that products and services provide fair value to retail customers)….. Certain AI-derived price-discrimination strategies could breach the requirements if they result in poor outcomes for groups of retail customers. As such, firms should be able to monitor, explain, and justify if their AI models result in differences in price and value for different cohorts of customers.”

The BoE also considered that existing general regulatory requirements could be read as requiring firms to have in place specific, fit for purpose governance arrangements for AI. These obligations include:

- ‘[a] firm must take reasonable care to organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively, with adequate risk management systems’;

- ‘boards should have the diversity of experience and capacity to provide effective challenge across the full range of the firm’s business and boards should pay close attention to the skills of its members.’ The FCA requires boards to publish on the diversity of their board members’ sills, and this could include on AI;

- There are rules on the accountability of executives called Senior Management Functions (SMFs). There is not yet a separate SMF for AI, and the BoE comments that “AI may not have yet reached a level of materiality or pervasiveness to justify such a dedicated function.” But the BoE has concerns that issues may fall between the cracks because AI responsibility is split across different SMFs under the current regulatory framework, including the chief operating officer, the chief risk officer and the executives in whose business line the AI is used. The BoE canvasses whether there should be a certification or sign off process to help clarify the individual responsibilities.

- The regulatory requirements around the resilience of systems used by financial firms are directly applicable to AI: for example, developing and implementing effective business continuity and contingency plans for AI systems that support an important business service. These existing operational resilience requirements and expectations will apply irrespective of whether the AI is developed in-house, or by third parties

Finally – and this is probably the key ‘weak point’ the BoE identifies in the current regulatory regime - many of the responsibilities and duties on firms under UK financial services regulation are framed in terms of taking ‘reasonable steps’. The BoE suggests that, given the unique features and risks of AI, it may be useful to spell out what are reasonable steps at each stage of the life cycle of AI.

Read more: DP5/22 - Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Visit Smart Counsel