The 1939 British Government poster ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ accurately summarises a recent study from the Tony Blair Institute (TBI) forecasting the impact of AI on employment:

Our best guess is that AI’s peak impact on unemployment [in the UK] is likely to be in the low hundreds of thousands and for the effect to unwind over time.

However, TBI cautions this optimistic outcome will require some innovative, fleet footed policy intervention by governments.

Significant impact on individual jobs

TBI’s premise was that AI would not replace entire jobs but tasks within jobs. Their model used O*Net database of 200,000 job tasks associated with 900 job categories, ChatGPT 4 was fine-tuned to consider various factors that might influence whether or not AI could perform job tasks, such as ethical considerations or the operating environment and to provide estimates of the amount of time that could be saved using AI, and these task-level results were aggregated to the occupation level to work out job impacts.

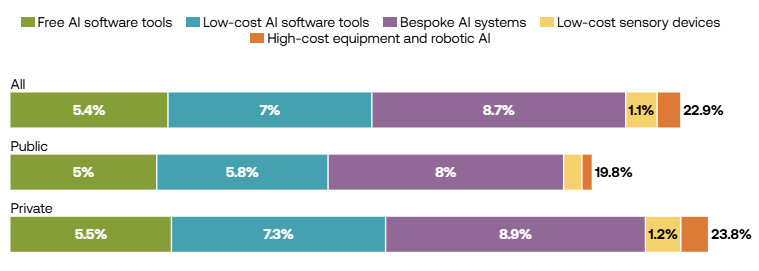

TBI tested the impact of different types of AI:

Free AI tools: such as Google’s Gemini, ChatGPT and DALL-E.

Low-cost AI software tools: such as Microsoft Copilot.

Bespoke or internally trained AI systems: such as enterprise-specific tools that would require training on proprietary data to unlock time savings.

Low-cost sensory devices: such as cameras and radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags combined with relatively basic AI.

High-cost equipment and robotic AI: such as scanners, drones and robots to provide medical diagnoses, monitor environments or aid in the completion of other complex or dangerous tasks.

The TBI modelling found the full implementation of AI could save up to 22.9 % of total workforce time (see figure below):

The AI replacement rate was lower for the public sector compared to the private sector because more public sector jobs were less suitable for AI, such as judges.

Off the shelf AI tools accounted for nearly 60% of the productivity gains from AI:

This suggests that overall productivity gains are likely to be sizeable since expensive labour can be replaced with cheaper forms of capital without the need for costly investments in hardware.

The results by worker characteristics were:

Job types: AI saved 45.8% of the time in administrative jobs, 26.5% of the time in professional jobs, 17.8% of the time in machine operator jobs and only 16.1% of the time in construction jobs. The TBI researchers concluded that occupations involving a significant amount of routine cognitive tasks are particularly exposed but much lower for occupations involving manual physical tasks because of the relatively limited ability of AI to automate complex physical tasks in a cost-effective way.

Age: 16-19 year olds are least exposed to AI (19.3%), 30-34 year olds are most exposed (25.2%) and exposure tails off for older workers (for example, 23.8% for 50-54 years old). The TBI researchers concluded this pattern partly reflects the changing nature of the labour force, with workers in the 30-34 year old band more likely to be highly educated and working in cognitive roles than younger employees (who are in the workforce rather than being at university etc.) and older employees (who may not have the same educational opportunities in earlier life).

Gender: in the private sector, women are 3% more exposed to AI replacement than men because more men are in manual jobs. While in the public sector, more men are AI exposed because many public service positions are highly female gendered, such as nursing and teaching.

Education: the starkest driver of AI exposure is education levels: 26.8% of employees with a university degree are AI exposed and high school graduates are 22.3% AI exposed, while those with no qualifications are only 19.3% AI exposed. The TBI researchers conclude: “These differences reflect a reversal in the historic trend of tech disruption, where lower and middle-skilled jobs have tended to be more impacted by automation”.

Why so optimistic?

While the TBI modelling shows AI could save nearly a quarter of current workforce time, the researchers argue this will not necessarily translate into job losses because:

With a more productive AI-enabled workforce, employers will be able to redirect freed-up time and effort into growing their businesses more efficiently.

Higher productivity will reduce prices, stimulate demand, grow revenue and flow through to higher wages reflecting that productive boon for employers.

Periods of rapid technological progress are often associated with new products, sectors and markets being created that result in new tasks for workers to do.

But TBI also acknowledges how bumpy the transition will be will depend on some uncertain timing issues:

How quickly AI is adopted by firms, the extent of productivity benefits that are realised whether firms choose to shed labour or retain their workforce, and how much and how quickly AI boosts demand for labour through higher output and task creation.

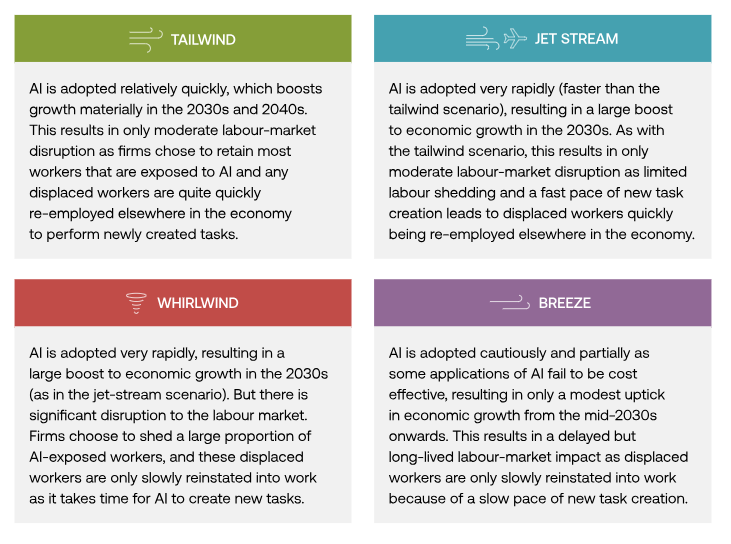

TBI models the following four scenarios:

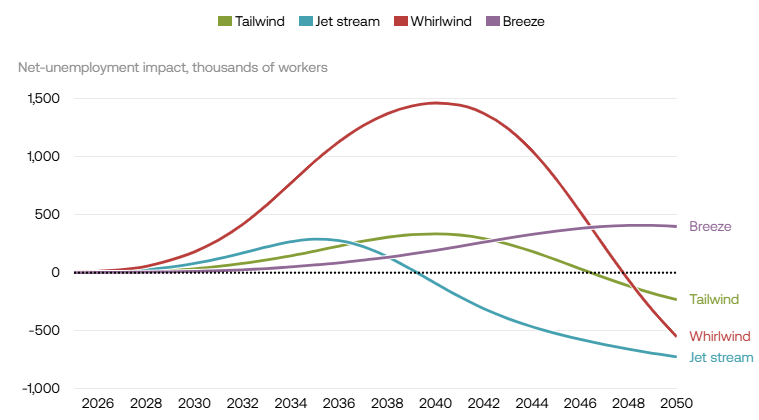

TBI models the net employment effects as follows:

TBI’s view is the tailwind scenario is the most likely:

Only one-quarter of time savings result in labour shedding.

While nearly 1.5 million UK workers will lose their jobs as a result of AI, this will occur incrementally as AI is rolled out, with 100,000 redundancies occurring in 2040 at peak AI rollout. The TBI researchers comment:

“To put that figure in context, there have been an average of 450,000 redundancies each year over the past decade, so even at AI’s peak of disruption, the risk of redundancy increases by scarcely one-fifth above its baseline level.”

Most of these displaced workers are expected to be reabsorbed into the labour force relatively quickly, soaking up the opportunities generated by AI. TBI notes that while past technology waves have seen a 10-year lag between the emergence of the technology and new job creation, they expect this will shorten to 5 years with AI given its capability and widespread adoption.

Even under this favourable scenario, women are likely to be impacted earlier and more deeply than men. This is because the off the shelf AI applications will be taken up more quickly, as a result the impact will be greatest in administrative job categories and women dominate in those jobs.

What should governments do?

The TBI cautions:

Many governments might decide to wait and see and react to disruption after the event. Others will seek to put safety first and intervene to establish as much control as possible so that change can be managed or minimised. Each of these approaches is mistaken. The first leaves policymakers at risk of seeming entirely unprepared; the latter is a charter for decline.

The TBI’s recommendations focus on how to improve the prospects of employees catching the new AI job wave by increasing AI skills through UK schools and training programs.

The more novel recommendations for labour force retraining are:

Self insure: The UK has the third lowest unemployment benefit in the OECD and UK household savings rates are only a third of the EU average. As a result, most UK employees do not have sufficient resources to bridge any significant lag period between loss of their job to AI and the emergence of new jobs and to retrain themselves for those new jobs. TBI recommended creation of LIFESPAN funds – ‘Lifetime Income Flexibility and Employment Savings Programme for Adaptive Needs’ – to provide an income buffer for unemployment. Employees would be mandatorily enrolled with a voluntary opt-out and employees would contribute 1% of their wages matched by employers.

Inhouse training: the UK Government should develop a free open source training assistant which employers could use to build their own tools using proprietary training data for more bespoke features and content. There should be R&D tax credits for employers developing AI training AI training co-pilots aimed at helping new and less-skilled workers quickly become more proficient.

Improved career guidance: the UK employment services should better utilise AI to systemically predict changes in the labour market at least a year in advance. This would provide a new public service for citizens to check their personalised risk of displacement on demand. AI also should be used to better match individuals to the right opportunity for them: for example, the Estonian Unemployment Insurance Fund uses AI to determine employment pathways for candidates and to determine the probability of finding a job.

Better information collection and exchange: Labour market surveys should collect data on the impact of AI on job quality, asking questions on how AI is affecting worker welfare through its role in decision-making, health and safety, the intensity of work, worker surveillance and enjoyment of work. Employers should be supported through establishing a Taskforce for AI-Workplace Disclosures which shares best practice to speed AI adoption, create meaningful dialogue between management and employees over AI implementation and mitigate impacts on employees.

TDI also recommends governments undertake scenario planning to ready their economies and workforces for a more radically different future.

For example, in a scenario where AI continues to advance rapidly and is capable of performing an ever-higher share of worker tasks, rapidly accelerating productivity growth could enable a shortened working week, as predicted by John Maynard Keynes in the 1930s. However, transitioning society to a shorter workweek would not be straightforward, particularly if the impact of AI were felt unevenly across the labour market.

Conclusion

TBI’s relatively optimistic picture of the impact of AI on labour markets has two potential challenges. First, while there has been rapid technological change over the last decade, productivity gains and new task creation have been very limited – a process known as 'so-so automation'.

TBI argues that, on the early evidence of individual firm productivity gains from AI deployment, it will be different but who really knows. Second, TBI is betting heavily on successfully retraining a large pool of displaced workers with the skills they need to take-up new AI-enabled jobs. The re-election of Donald Trump appears to illustrate that, while transformative economic change may be beneficial overall, there is a stark deep divide between the ‘losers’ and ‘winners’ and that governments have been singularly unsuccessful in addressing this challenge.

Read more: The Impact of AI on the Labour Market

Peter Waters

Consultant