There’s been a lot of noise about the use of AI as a tool for health professionals to improve diagnosis, develop treatment plans and monitor patients’ conditions. But in the hands of patients could AI improve their ability to understand and participate in decision making about their own treatment? In a sense, by leveling up the playing field with health professionals.

Cornell University researchers (Yuexing Hao, Zeyu Liu, Robert N. Riter and Saleh Kalantar) recently trialled a patient-centred Artificial Intelligence SDM (shared decision making) system for older adult cancer patients who lack high health literacy to become more involved in the clinical decision-making process and to improve comprehension toward treatment outcomes, with positive results.

The Holy Grail of patient empowerment

There is widespread recognition that SDM between a patient and the health professionals treating them can play a vital role in clinical practice by fostering enduring therapeutic communication and patient-clinician relationships. But those of us who have had to navigate the health system or watch family and friends do so know that SDM is often an unmet aspiration. As the Cornell study put it (more kindly than many patients might):

Many clinicians today are extremely pressed for time, partly due to the staff shortages that remain in the wake of the pandemic and the worsening clinician-to-patient ratios in many healthcare settings. As a result of these time pressures and limited communications training, many clinicians are unable to pursue effective SDM practices. Patients also sometimes confront obstacles that may limit their ability to rationally evaluate potential benefits and risks, and strained healthcare providers may not have adequate funding, staffing, or communications training to engage in detailed SDM processes.

Patients aged over 70 represent (in the US) 42% of all cancer patients, but face particular challenges in participating in SDM:

Their health situation is often complicated by more co-morbid conditions.

Decision-making for older adult cancer patients is situated within a social context, where as other individuals, particularly family members, caregivers, and healthcare providers, contribute insights and perspectives on behalf of the patients.

Often with more limited education and slowing mental sharpness, it is not surprising another study of older patients want to receive relevant information regarding their illness and treatment in a language they understand, free of medical jargon and at a speed that allows them to process this material.

The Cornell researchers wanted to test the hypothesis that new technologies such as AI, while they should not be a substitute for human clinician-patient interactions, “provide intriguing modalities for stepping into this gap to help promote SDM, particularly when it comes to enhancing communication between highly specialized professional health care providers and their patients”.

The Cornell Study

The pilot was conducted in two stages:

Study 1: interviews with older patients with chronic diseases (mean age of 72) and clinicians (mean 12 years of specialist practice) to evaluate the perspectives of older adult cancer patients and clinicians regarding the SDM process and ways in which technology might improve it. The patients had a range of chronic conditions, including thyroid, breast, and prostate cancers. The clinicians had expertise in cancer, nursing and psychiatry.

Study 2: based on this input, a prototype SDM AI system, called i-SDM, was developed and then usability interviews were conducted with older adult cancer patients (mean age of 69.22 years) and specialist cancer clinicians (mean practice of 13.6 years) to evaluate its perceived utility.

In study 1, patients were asked which sources (human and otherwise) they currently used to try to decode their diagnosis and treatment. For their part, clinicians were asked to describe how they delivered a recent clinical decision to an older patient and the difficulties and barriers they encountered.

The study 1 results were unsurprising. Patients consistently “expressed frustration and difficulty in comprehending technical terminology associated with their medical conditions, leading to confusion and hampering their ability to actively participate in collaborative decision-making.” Patients said the most glaring gap (or their perception of a gap) in the information provided by their treating doctor was the potential harms and adverse effects of treatments, potential drug interactions and other safety issues. Most patients spend hours googling their condition looking for understanding and answers. Patients also expressed strong opinions about their health care and wanted to make their own decisions, currently often based on their own googling: “I try to stay away from surgery as much as possible, and so I research alternative approaches to things. When I found a reasonable alternative approach, I always attempted it first.”

While clinicians expressed commitment to an SDM approach, they also expressed concerns:

mostly related to patients’ abilities to assess medical information objectively and analytically. This included the potential for patients to fixate on treatments that offered potentially transformative solutions while ignoring their low chances of success and potential risks. Several of the clinicians also expressed concern that miscommunications during the SDM process might lead to inaccurate patient expectations, or to clinicians not accurately understanding their patients’ goals. Finally, clinicians expressed concerns that patients might rely on poor-quality or overgeneralized information resources when understanding their conditions, and would not be able to evaluate the best evidence-based approach for addressing their particular circumstances in a treatment plan.

So, how can technology beyond googling bridge this gap between patient and specialist?

The design of i-SDM

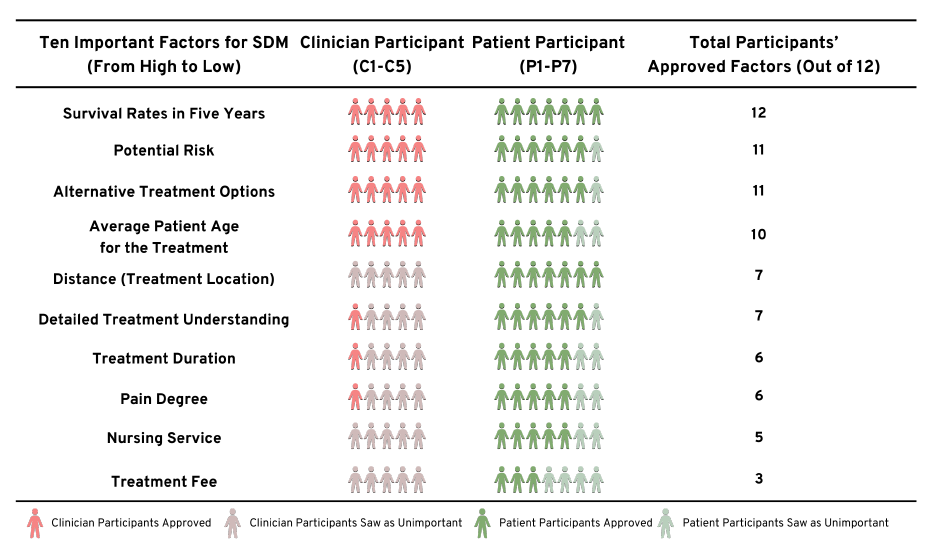

There was both a degree of correlation but also differences between patients and health professionals in identifying the 10 most important factors the i-SDM system should be capable of addressing. As depicted below, clinicians gravitated strongly to four factors: potential medical benefits or effects of treatment, potential risks, detailed information about alternative options and patient ages at which the treatment was most valuable. However, patients’ concerns ranged over more factors, including pain, their ongoing treatment (nursing) and cost.

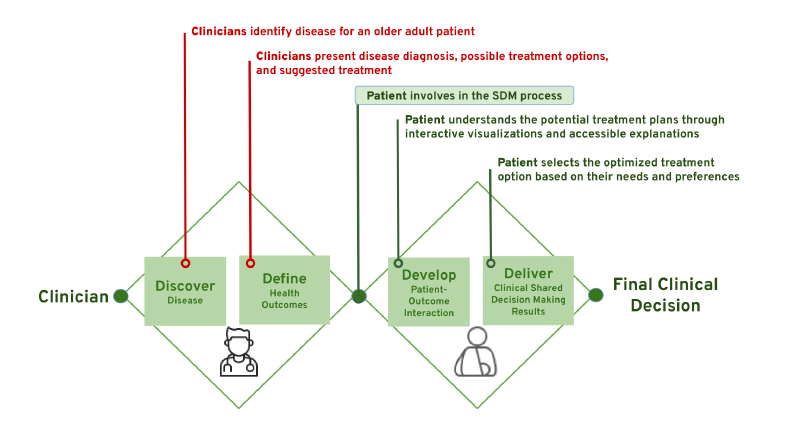

Due to the specialists’ view about their role and the ideal point at which SDM becomes of value to patient and specialist, the Cornell team designed the i-SDM platform around a double diamond approach, depicted below. The first diamond is the clinician’s sole domain - diagnosis and options for a treatment plan. Patients become involved in the second diamond, learning more about each clinical treatment option and voicing their outlooks and preferences.

In diamond 2 the i-STM has a structured 6 step process to assist the clinician to walk the patient through their diagnosis and proposed treatment options. In step 1, patients begin by indicating the factors they are most concerned about, out of the 10 overall metrics we developed from the interviews. In step 2 they are asked to confirm basic information about the patient’s diagnosis and personal demographic factors. In step 3, patients can start to compare the treatment options by looking at associated survival rates. Step 4 presents potential side effects and risks and step 5 presents other factors as selected by the user out of the 10 possible factors identified by patients as a whole (see above). Finally, step 6 presents a summary overview of the treatment option factors and links to more in-depth information.

The design of the i-SDM takes onboard study 1 comments:

From patients: it is easier to understand complex medical information when presented graphically or visually.

From clinicians: about patients accessing inaccurate or misleading information online by embedding in the i-SDM platform links to higher quality information.

The study results

The visual presentation of data was a big hit with patients and specialists alike.

Comment from stage three ovarian cancer patient:

I know the clinicians would say, Well, surgery and radiation, both are 98% and active surveillance is 96%. Unless you’re going to sit there and take lots of notes, that information isn’t going to stick, especially to older cancer patients like me. But it is wonderful that you can actually see predictive survival. There’s only a 2% difference in survival, and it’s still really good.

Comment from oncologist 11 years in practice:

...[clinicians’] preference may lean toward verbal communication, delivering essentially the same information verbally as the i-SDM system presents visually. However, I do see a valuable role for this in the clinic that we could display it briefly, maybe for 2 or 3 minutes, while explaining things [to cancer patients] (comment from oncologist 11 years in practice)."

The six step-by-step structure, because it is a discipline on the specialist and an opportunity for the patient, seems to have contributed to a more open dialogue:

Through this step-by-step SDM [process], cancer patients like me have the opportunity to learn each treatment option’s survival rates and risks, acknowledge various cancer research or resources, and I can calm myself down even [cancer] has so much uncertainty and is very complex.

There was also a sense amongst the clinicians that patients are going to go online anyhow, and so it is better they have the confidence of more accurate and more personalised information delivered through the specialist AI app. The Cornell researchers commented:

Such improved knowledge and engagement could potentially lead to better health outcomes, as some patients acknowledged: ‘When you feel confident and optimistic about a clinical decision and staff, your medical or health outcome will be better’ (...thyroid and triple-negative breast cancer patient). One likely outcome is improved treatment adherence, as patients may better comply with the chosen treatment plan if they feel that they understand it and have an active role in the decision-making process.

There were also some doubting Thomases amongst both clinicians and patients:

Some clinicians were concerned that i-SDM which may be required to allocate extra time and energy to explain to patients. A clinician who refused point blank to participate in the i-SDM pilot stated that having to negotiate with patients about treatments could lead to suboptimal outcomes and most patients lacked the background necessary to understand medical information and make a good decision.

While AI does allow more personalisation, some clinicians and patients expressed concern that AI could not capture the complexity of cancer treatment:

A lot of cancer patients need personalized care because their scenarios are pretty complex. That’s why AI could only cover some common basic diseases but not complex diseases like cancer. For example, I had knee surgery, and got sepsis three months before being diagnosed with breast cancer. AI can predict each singular disease, but the combination would be very complex and need senior doctors’ inputs (stage 1 breast cancer patient).

Some patients considered that SDM wrongly shifted some of the burden and responsibility for their treatment onto them and they wanted the specialist to make a knowledgeable decision on their treatment.

Conclusion

The Cornell researchers drew the following conclusions from their pilot:

The i-SDM platform reinforced, rather than cheated, the patient-clinician relationship: most patients affirmed their specialist’s recommended treatment program.

This was because patients clearly understood AI would never be a substitute for clinicians’ decision-making. Instead, by providing personalised analytics and well-vetted data, patients can feel more confident in their specialist’s recommendations.

There is also a way to improve the use of AI as a tool in the patient-clinician relationship:

AI needs to be trained on more accurate data on the impact of comorbidities.

The generalised public distrust of AI needs to be especially addressed in the medical realm by developers, such as by better explaining how AI works and stronger privacy protections.

Sadly, you also have to wonder whether hearing the bad news from a computer rather than a human shows how online-habitual we have become.

Read more: Advancing Patient-Centered Shared Decision-Making with AI systems for Older Adult Cancer Patients

Peter Waters

Consultant