Shortly after 280 million fans in China watched Google’s DeepMind AI defeat a professional Go player in 2016, the Chinese Government announced an ambitious AI development plan. Less than a decade later, in what is described as a ‘Sputnik moment’ for AI, a little-known Chinese start-up called DeepSeek, released an AI model with capabilities matching Open AI’s and Anthropic’s models developed and trained at one-tenth of the cost.

China sees the United States as a leader in the artificial intelligence (AI) industry and itself as a “leading pursuer”. Kai-Fu Lee, the chief executive officer of the Chinese AI startup 01.AI, claimed that the company is six to nine months behind US AI leaders but is catching up rapidly.

But what is more interesting is that China’s AI development appears headed down a very different path to Silicon Valley.

Frugal innovation

In 2024, private AI investment in the US was US$109.1 billion, 11.7 times greater than the amount invested in China, the next highest country. Even more starkly, US private investment in generative AI grew from just under US$25 billion in 2023 to over US$29 billion while in the same period Chinese private investment in generative AI grew from a little under US$2 billion to US$2.11 billion.

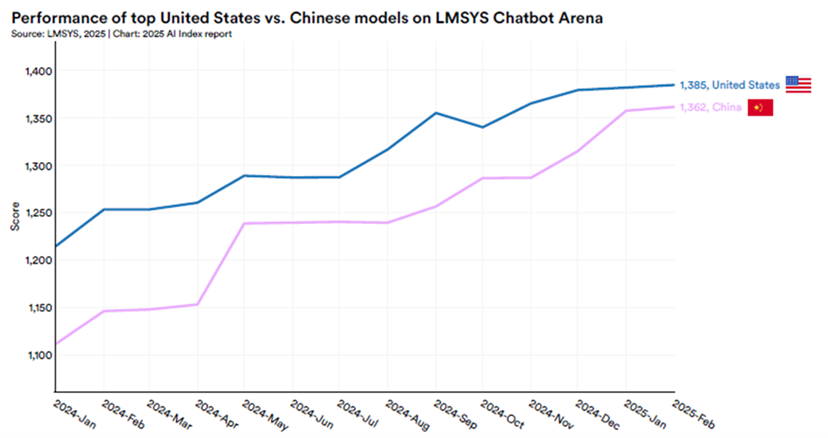

Yet Chinese generative AI models are closing the performance gap with US-developed models. On the LMSYS Chatbot Arena benchmark, the best US model outperformed the best Chinese model by 9.26% in January 2024, but this gap had shrunk to 1.7% by February 2025.

Necessity as the mother of invention

In the West, large language model (LLM) development and training is an exercise in brute force: throw huge amounts of data (40% of the internet), at vast amounts of computing capacity (compute used LLM training grows at four to five times per year), powered by advanced chips (NVIDIA A100/H100 chips double computation speeds) and requiring huge capital investment (up to US$100 million) to produce models of overwhelming scale (over 100 trillion parameters).

While China has data at scale, China only controls about 15% of total AI compute compared to the United States controlling about 75%. In the face of the US export bans on advanced chips, Beijing is supporting the development of domestic alternatives, such as Huawei’s Ascend series, but they lag behind in performance and production volume. A recent study of 20 Chinese LLMs found 17 models were built using chips produced by the US-based firm NVIDIA and only three models built with Chinese-made chips.

Overcoming these obstacles has required Chinese developers like DeepSeek to innovate in algorithmic design and training techniques to squeeze more AI capability out of less compute:

DeepSeek’s model doesn’t activate all its parameters at once like GPT-4. Instead, it uses a technique called Mixture-of-Experts (MoE), which works like a team of specialists rather than a single generalist model. When asked a question, only the most relevant parts of the AI ‘wake up’ to respond, while the rest stay idle. This drastically reduces computing needs.

DeepSeek also designed its model to work on less powerful NVIDIA H800 GPUs rather than the export-banned H100/A100 chips. By using an assembly-like programming method, DeepSeek could control how AI interacts with the chip at a lower level, allowing it to squeeze more performance out of less powerful hardware.

Training was also optimised to reduce expensive human fine-tuning. While most developers rely on large teams of human reviewers to manually refine AI responses during training, DeepSeek automated much of this process.

A different AI architecture

China’s AI ambitions are bigger than mimicking US AI developments at a lower cost. China is building a very different architecture of ‘embodied AI’ which is shaped by a real-time, physical engagement with the world.

Georgetown University researchers (Hannas, Chang and Chou) consider that this vision started with the building of ‘digital twins’ of road networks in Chinese cities to help with traffic management, but has deepened into building a ‘large-scale social simulator’ in which people, social behaviours, communal patterns of living and political institutions are all simulated. One of China’s leading AI scientists, Wu Zhiqiang, has described this approach:

[It] can practice massive intelligent agent interactions in a 3D modelling simulation environment, realising multi-level complex system simulation and the emergence of group intelligence from individual behavior to overall city operation… It builds a virtual social system containing millions of people through multidimensional data fusion and dynamic interactive modelling. It uses multi-agent value modelling and digital twin technology to accurately deduce social operating rules, simulate the long-term impact of different social decisions and provide forward-looking decision support.

The metaverse within which the AI ‘lives and learns’ has a specific purpose: the intention is that the AI will not only learn from but also optimise human behaviour in line with national policy priorities, as the Georgetown researchers note:

The basic intent is to start from the brain, use human information processing methods to build a virtual brain and use brain-computer interaction to realise the fusion and integration of a biological brain, virtual brain and human computer intelligence. In this view, values injected into the model during its development, in part to advance and safeguard the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) priorities, motivate the AI to explore its environment and ensure what it learns and outputs conform to the CCP’s needs. The simulator is being endowed with a ‘human-like mind’ that possesses emotions, needs, motivations and cognitive abilities.

Another Sputnik moment?

On 6 March 2025, Chinese developers released Manus, the world’s first fully autonomous AI agent, born out of this environment of embedded AI.

Before Manus, autonomous agents developed in the West worked in narrow vertical domains, such as in finance or logistics. Manus is a general-purpose agent and can perform a wide variety of tasks, from generating research papers, designing marketing campaigns or building entire websites from scratch.

This is possible because Manus is not a single agent, but rather a coordinated swarm of sub-agents performing specialist elements of the larger overall task, with a central agent orchestrating the sub-agents’ activities. Manus operates in the cloud and can interact directly with the outside world. Users can set a task, log off, and Manus will complete the task and notify users once finished.

AI safety

While Chinese President Xi Jinping emphasised “self-reliance” and the creation of an “autonomously controllable” AI hardware and software ecosystem, China is, to the surprise of many, increasingly engaged with other leading AI nations on AI safety.

The UK government made a strategic decision to invite China to the Bletchley Park AI summit. Leading Chinese AI experts participated in the preparation of the international expert report on AI safety led by AI scientist, Yoshua Bengio, which warned of the existential threat posed by AI. At the Paris AI Summit early this year, China’s former vice minister of foreign affairs, Fu Ying, announced the launch of the China AI Safety and Development Association (CnAISDA), China’s self-described counterpart to the AI safety institutes in the UK, Canada, France and South Korea.

Carnegie Endowment researchers (Singer, Elmgren and Guest) have pointed out that back in 2021, the ‘Ethical Norms for New Generation Artificial Intelligence’ published by the Ministry of Science and Technology included a call to “ensure that AI is always under human control”. One of the leading Chinese AI experts Andrew Yao, a Turing Award winner, said:

We have suddenly found a way to create a new species that is many, many, times more powerful than we are. And are we sure we can live with it? Certainly, if we don’t do anything, we are going to be eliminated. There’s absolutely no question about it. Whether due to the nature of the computer or due to bad, malicious, actors, I think there would be a lot of destruction.

However, CnAISDA appears to have limits. Unlike other AI safety institutes, such as in the UK, it does not have a role in testing and verifying the safety of domestically developed AI models. Its focus is mainly on international engagement on AI safety. As the Carnegie researchers observe:

While Chinese leaders have signalled concern about AI safety, their immediate priority has been promoting AI innovation to stimulate economic growth, creating a potential tension for CnAISDA between engagement in international safety efforts and the pursuit of China’s development-focused domestic agenda.

Conclusion

While China’s AI policy reflects a highly centralised governance model, there may be lessons for economies without the embedded scale and momentum of Silicon Valley.

First, we say company boards need to deeply instil AI expertise, but what about our political leaders and bureaucrats? China’s cabinet holds regular half-day study sessions on a topic chosen by President Xi Jinping and AI is a common topic.

Second, China’s AI policy is built around a strategic architecture of three integrated levels functioning as a unified ecosystem. The foundational layer provides the communications and computing infrastructure through paired AI computing centres. The technical layer hosts major AI platforms, while the applications layer encompasses small and medium-sized enterprises across manufacturing, healthcare, education and urban management sectors. Policies promoting vertical and horizontal interaction include making models available on an open-source basis and creating shared data pools.

Third, while the embedding of the governing political party’s values into AI systems would be unacceptable in the West, it is also important to recognise that AI models built in the West are not values-neutral and that governments have a role to ensure models reflect our own social, cultural and political values. As the Australian Assistant Minister for Productivity and Competition said recently:

If AI is going to help us all, we can’t leave it to be designed solely by 40-something men named Sam.

Peter Waters

Consultant