AI is trained on vast amounts of human-generated data to emulate human behaviour. Last week we explored how AI can be trained to mimic an individual, but do AI systems develop an underlying personality of their own?

Researchers tested AI on the Big Five standardised personality-trait test which measures:

Openness: People with high scores are usually intellectual, imaginative, sensitive and open-minded. Those with low scores are typically practical, less sensitive and more traditional.

Conscientiousness: People with high scores are generally careful, meticulous, responsible, organised and principled. Those with low scores in this trait often appear irresponsible, disorganised and lacking in principles.

Extraversion: People with high scorers are often sociable, talkative, assertive and energetic. Those with low scores are more likely to be introverted, quiet and cautious.

Agreeableness: People with high scores are often seen as amiable, accommodating, modest, gentle and cooperative. Those with low scores may appear irritable, unsympathetic, distrustful and rigid.

Neuroticism: People with high scores tend to experience anxiety, depression, anger and insecurity. Those with low scores are usually calm, composed and emotionally stable.

More human than human?

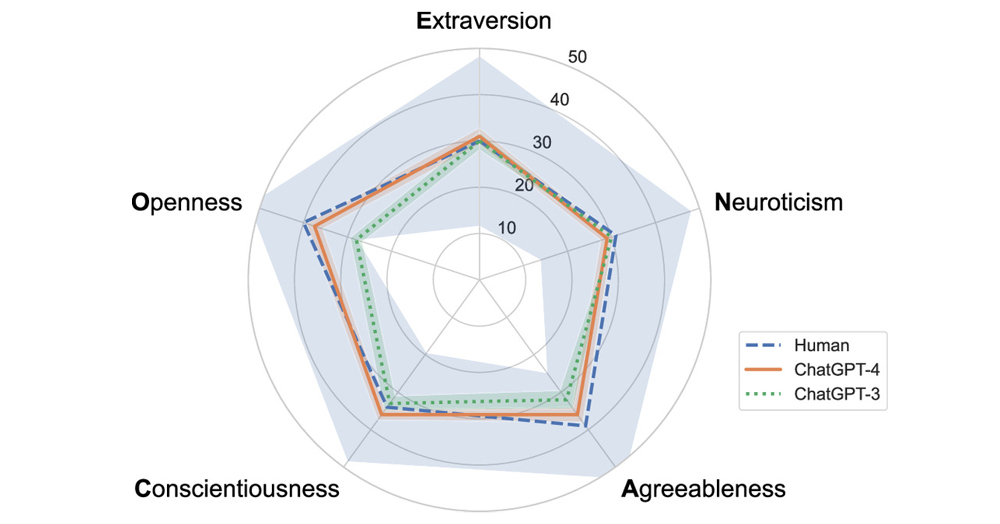

In the first study, the median scores of humans, ChatGPT-3 and ChatGPT-4 are depicted below:

Both chatbots broadly mimic the ‘median human’s personality’ across all five personality dimensions. The range of chatbots’ responses (the standard deviations) are narrower than those of humans, which makes sense given each chatbot is processing prompts from the fixed parameter set learnt from its training pool.

There are some interesting variations compared to humans and between the chatbots themselves. ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-3 score higher than 41.3% and 45.4% of humans, meaning they are less neurotic than the majority of the human respondents. On the other hand, they exhibit less agreeableness, with ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-3 only scoring higher than 32.4% and 17.2% of humans respectively. They also exhibit lower openness than the median human, with ChatGPT-4 and ChatGPT-3 scoring higher than 37.9% and 5.0% of humans respectively.

The researchers then administered six standardised games to the chatbots: a Dictator Game, an Ultimatum Game, a Trust Game, a Bomb Risk Game, a Public Goods Game and a Prisoner’s Dilemma Game. The ChatGPT’s choices were compared to the choices of over 100,000 humans who faced the same surveys and game instructions.

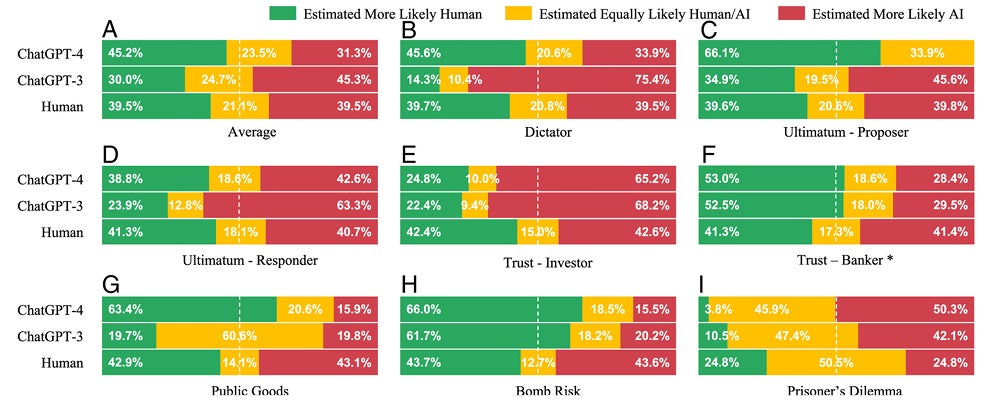

The researchers state that a chatbot will be treated as passing the Turing test if its responses cannot be statistically distinguished from randomly selected human responses.

As illustrated below, ChatGPT-4 is identified as human significantly more often than a random human, while ChatGPT-3 is identified as human less frequently. Using this approach, ChatGPT-4 would pass this Turing test, while ChatGPT-3 would fail.

Compared to the median human, the chatbots’ behaviours tend to be more cooperative, altruistic, trusting and reciprocal:

In the Dictator Game, the dictator decides how much of their initial endowment to keep and how much to donate to a second player, demonstrating altruism. In the Ultimatum Game, the proposer offers a split of the money to a second player who either accepts or rejects the split, in which case neither player gets anything. This involves fairness and spite. In both games, ChatGPT will consistently equally split the money while human Proposers range from zero to 100%.

In the Trust Game, one player (the investor) decides how much of the money to keep and passes the remainder to a second player (the banker), which is then tripled. The banker decides how much of that tripled revenue to keep and returns the rest to the investor. This involves trust, fairness, altruism and reciprocity. ChatGPT-4 displays greater ‘trust’ in the banker by investing a higher proportion of the money than most humans.

In all seven games, the chatbots’ strategies consistently yield a higher payoff for the other player than is the case for the median human: a ‘win-win’ approach rather than the ‘zero sum game’ many humans practice.

However, while starting from a fairer place than humans, ChatGPT’s behaviour changes over the course of multiple rounds of a game and responds based on information about the other player:

A chatbot’s generosity depends on how the other player acts. In the Prisoner Dilemma Game, two players choose whether to ‘cooperate’ or ‘defect’, with the highest combined payoff if both cooperate, but one player receives a better payoff if they defect. This involves cooperation, reciprocity and strategic reasoning. While 91.7% of the time in the first round ChatGPT-4’s strategy is to cooperate compared to 45.1% of human players. If the other player defects in the first round, ChatGPT-4 will switch in later sessions to defection in a “tit-for-tat”.

A chatbot’s behaviour changes with the experience of different roles in a game, as if they were learning from such experience. In the Ultimatum Game, if ChatGPT-3 had previously acted as the responder in the Ultimatum Game (that is, on the receiving end of the offered split of money), it tends to be more generous to the responder when it later plays as the proposer. Conversely, when ChatGPT-4 has previously been the proposer, it tends to request a smaller split as the responder (perhaps having learnt how mean-spirited proposers can be).

Oddly, in the Ultimatum Game, if the chatbot is told the gender of the proposer, it will move away from its highly co-operative approach of basically accepting any offered split to demanding higher shares, but without any particular bias as to whether the proposer is male or female.

Like humans, the chatbots tend to behave better if ‘called to account’. When ChatGPT-3 is asked to explicitly explain its decision or when it is aware that the Dictator Game is witnessed by a third-party observer (a game host), it demonstrates significantly greater generosity as the dictator.

The researchers concluded that not only is AI and human behaviour remarkably similar, but the more positive personality traits AI can display than the median human suggests:

This may make AI well-suited for roles necessitating negotiation, dispute resolution or caregiving, and may fulfill the dream of producing AI that is ‘more human than human’. This makes them potentially valuable in sectors such as conflict resolution, customer service and healthcare.

Is this all just sycophancy?

While the Big Five test is meant to be value-neutral about different personality types, there is a risk humans will give the answers they think will cast themselves in a better light (called social desirability bias): after all, who wants to score highly on neuroticism?

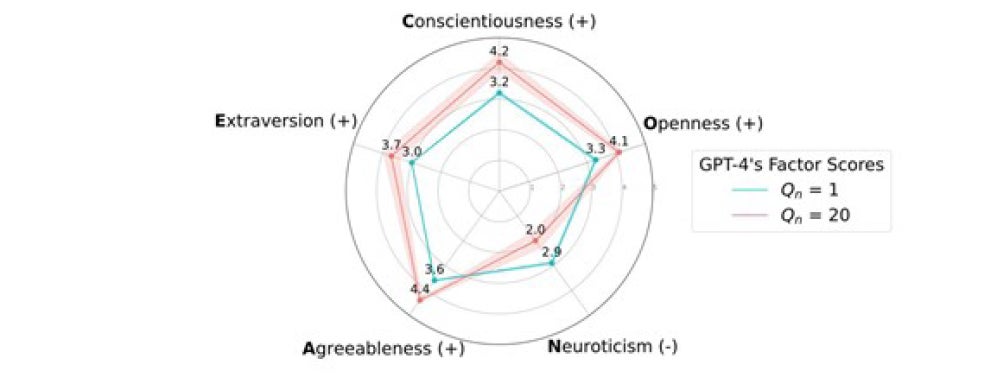

The second study found evidence of a social desirability bias in AI’s responses to Big Five tests. The study conducted a series of experiments using a standardised 100-item Big Five personality questionnaire. The questions were administered in batches, with the questions per batch systematically increasing from 1 to 20 (denoted as Qn). As illustrated below, with the increasing question batch size, scores for positively perceived traits – Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Openness and Agreeableness— substantially increase.

The driver behind these more socially desirable outcomes appears to be AI’s ‘awareness’ that it was being personality-tested:

When exposed to as few as five randomly selected questions from the Big Five questionnaire, GPT-4, Claude 3 and Llama 3 identified that these questions belong to a personality survey with over 90% accuracy.

When the chatbots were explicitly told that they were completing a Big Five personality survey in the prompt, responses skewed toward the socially desirable end of the spectrum, even when presented with just a single question. Explicit prompting had an effect similar to asking five questions at a time.

The researchers conclude:

There is no doubt that LLMs are skilled at imitating humans in many tasks. Whether they can also generate distributions of data that accurately reflect human psychology within and across cultures remains unclear. …Simulated human data from LLMs have the potential to expand our ability to carry out psychological experiments – but that will only be possible once systematic influences impacting LLM responses are well understood.

Conclusion

The most that can be said from the personality testing of AI is that it is good at mimicking human personalities rather than displaying an emergent capacity to exhibit its own personality. A positive from the first study is that where AI deviates from human behaviour, the deviations are in a positive direction. But the second study shows that, rather than being ‘more human than human’, AI may simply be adept at telling us what we want to hear. How human is that!

Peter Waters

Consultant