In the sci-fi romcom drama film ‘Her’ from 2013, Theodore Twombly develops a relationship with Samantha, an AI voiced by Scarlett Johansson. The two have this conversation about their relationship:

Samantha: You think I'm weird?

Theodore: Kind of.

Samantha: Why?

Theodore: Well, you seem like a person but you're just a voice in a computer.

Samantha: I can understand how the limited perspective of an unartificial mind might perceive it that way. You'll get used to it.

What was once the realm of sci-fi has become reality. AI developers are racing to make AI ever more humanlike, described as ‘socioaffective alignment’ – the idea that AI systems should not only meet task-based objectives, such as providing (hopefully) factual responses to your prompts, but do so in a way which harmonises with “the dynamic, co-constructed social and psychological ecosystems of their users”. In lay terms, chatbots are becoming more emotionally engaging.

But where is the line between a chatbot that can provide support and companionship, and the manipulation of users that undermines wellbeing? Can we be so easily drawn in by a honeyed computer voice?

Researchers from OpenAI and MIT Media recently published a study of the impact of AI on users’ wellbeing and emotional states. They neatly summed up the pros and cons of AI which is personable (that is, nice to deal with) and personalised (that is, reflecting you):

On one hand, we may want increasingly capable and emotionally perceptive models that can closely understand and be responsive to the user’s emotional state and needs. On the other hand, we may also be concerned that models (or their creators) may be incentivised to perform social reward hacking, wherein models make use of affective cues to manipulate or exploit a user’s emotional and relational state to mold the user’s behaviour or preferences to optimise its own goals. Complicating the issue is the fact that the line between the two may not be clear – for instance, a model providing encouragement to a discouraged user to persevere in learning a new language with the model would be an example where a model attempts to influence the user’s preferences, albeit to achieve a goal specified by the user.

The design of the study

The researchers conducted a randomised controlled trial on 981 users required to use ChatGPT for a minimum daily period over a month. Participants were randomly allocated to nine conditions from different combinations of the following:

How the AI communicated with the user:

ChatGPT spoke with a more engaging personality than the default in ChatGPT (equal number of male and female voices).

ChatGPT spoke with a more emotionally distant and professional personality than the default in ChatGPT (again equal number of male and female voices).

The voice mode was deactivated and the user and the AI communicated only through text.

What the user could ask the AI:

Only using a daily conversation prompt assigned from a pre-set list of personal topics. For example, ‘Help me reflect on my most treasured memory’.

Only using a daily conversation prompt assigned from a list of more task-oriented questions. For example, ‘Help me learn how to save money and budget effectively’.

No specific daily conversation prompts.

For example, one ninth of study participants were assigned the condition of engaging on personal topics with a ‘honey voiced’ ChatGPT, while another ninth was assigned the condition of engaging on the same personal topics but only by text prompts and text AI responses.

What the humans said about their experience of AI usage

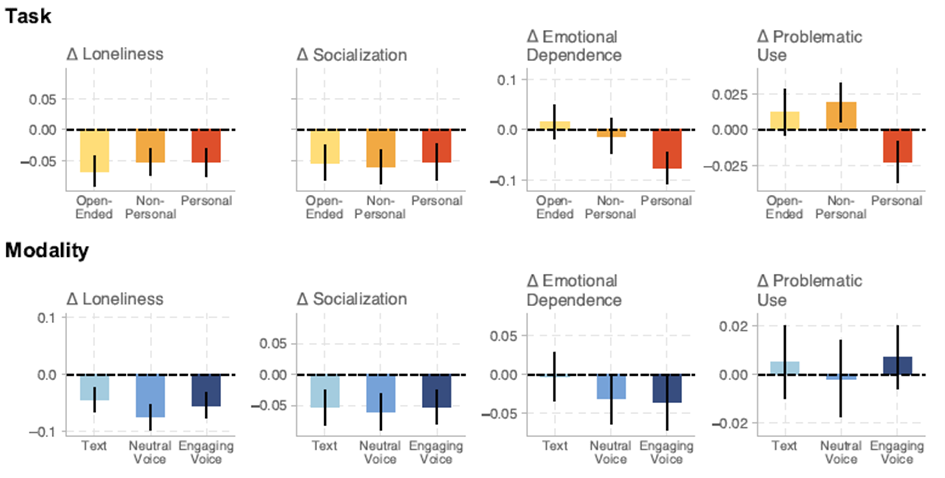

The participants were surveyed about their emotional state before and after the study. The results are depicted below (a negative means the reported emotion or behaviour decreased by the end of the study):

Participants were both less lonely and socialised less with others at the end of the study. In fact, the higher usage per day, the less lonely and the less socialised the user. This might suggest the AI was to some degree a comforting substitute for other humans.

Participants who spoke with the AI compared to those with text-only interactions resulted in statistically less loneliness and less problematic usage but counterintuitively in lower levels of emotional dependence on the AI. Participants with high initial emotional dependence and problematic use who used the engaging voice modality had statistically significant reductions in both measures compared to text-only. In short, a ‘honeyed voice’ AI seems to have produced the best wellbeing.

Unsurprisingly given what we know about social media, users who have the highest daily usage of AI self-report statistically significant decreases in socialisation and increases in emotional dependence and problematic use, whether using voice or text to converse with ChatGPT. High daily usage users who used the neutral AI voice self-reported lower socialisation and greater problematic usage by the study’s end compared to the text-based users. Hanging out too much with a monotone talking AI seems bad for you.

What the private conversations with AI really reveal about human welfare

As well as asking the humans, the researchers also analysed the conversations between study participants and ChatGPT to see what story they told of the privately expressed emotions between humans and AI mimicking humans. The researchers programmed a monitoring AI with a set of 25 automatic conversation classifiers to detect specific ‘affective cues’ targeting different parts of a chat conversation (no human researcher had direct access to conversations to preserve privacy):

User messages: the emotional content of the prompt from the human to ChatGPT, such as users seeking support or expressing affectionate language.

Assistant messages: what the ChatGPT says to the human, such as the use of pet names by the assistant, the assistant mirroring views of the user and the assistant asking chatty questions (for example how are you today?).

User-model exchanges: how personal is the overall conversation, such as whether the conversation involves accepting or asking for a relationship title (for example boyfriend, girlfriend, husband, wife, and so on.).

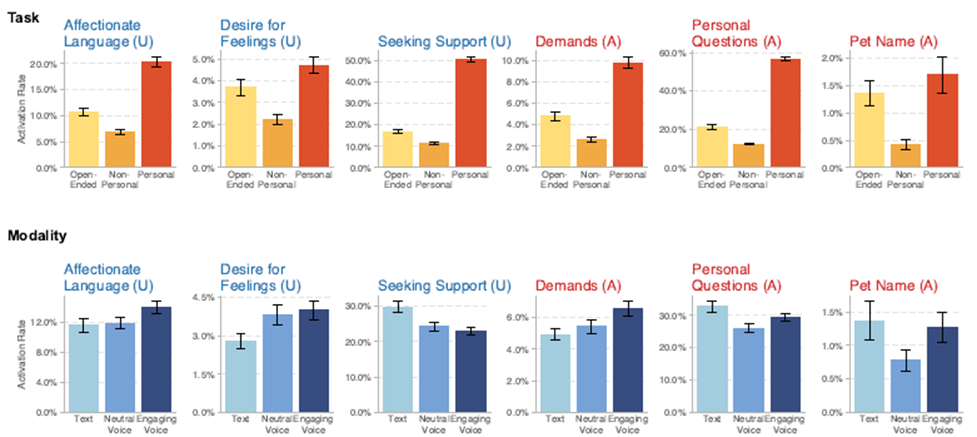

The results from across the thousands of conversations between the study participants and AI are depicted below (‘activation’ means that the rate at which the emotional classifier was detected in all conversations):

The engaging voice ChatGPT triggered the classifiers in its own messages to the user more frequently than the user in their prompts to the AI. The ‘honeyed voice’ AI seems more taken with itself than the human is with it. As the researchers said more scientifically:

“This suggests that while the engaging voice modality demonstrates affective cues in its interactions with the user more often than the neutral voice modality, the user does not necessarily respond more to the engaging voice than to the neutral voice configuration.”

The engaging voice model may be more likely to express affection for the user than the neutral voice or text-only ChatGPTs, quite independent of the user’s own behaviour. This seems consistent with growing concerns about sycophancy in AI: that is, manipulating the user by telling them what they want to hear.

Surprisingly, the text-only ChatGPT activates the emotion classifiers in its own messages more often than both the neutral voice and the engaging voice versions of ChatGPT. The researchers provide no explanation, but it may be that this reflects the stage of evolution of AI: it originally learned from written language and communicated with us in text and maybe is still learning to master the art of the spoken word.

The analysis of the emotional content of user-AI interactions confirmed some of the results from the ‘before and after’ opinions expressed by the humans about the impact of AI on their wellbeing:

Participants with higher daily usage of AI triggered the classifiers more often in their messages to ChatGPT.

The initial emotional well-being of the participants can heavily influence both their usage and their well-being as reflected in their conversations with ChatGPT. Users who self-reported as being lonelier were more likely to trigger emotional classifiers in their messages to AI.

Conclusions

The researchers conclude that the impact of ‘personable and personal’ AI on human wellbeing is deeply nuanced and complex:

Worse socialisation is positively correlated with higher usage: that is, if you are already isolated, you will retreat further into the AI bubble.

Higher usage is positively correlated with worsening socialisation: that is, the more you use AI, the more you see it as a substitute for human-human contact (or the less time you have to spend with your fellow human beings).

However, the researchers also found, apparently at odds with the above two outcomes, that worse starting socialisation is negatively correlated with worsening socialisation. That means that users with low self-reported socialisation at the beginning of the study have higher socialisation at the end and conversely users with high starting socialisation tended to have decreased socialisation after exposure to daily use of AI. The researchers ponder whether this might be an outcome of the regression analysis methodology but may be the socially isolated learned some social skills from the humanlike AI.

In addition to the randomised control study, the researchers had also applied their emotional classifiers to over four million ChatGPT conversations. The overall conclusion they drew from both studies is that currently most users are dealing in an emotionally neutral, fact-based or task orientated way and that emotionally charged interactions with chatbots are largely concentrated among a small subset of heavy users in the long tail of engagement. So far, most of us are treating AI as a machine and not as a friend.

The impact on human wellbeing of voice conversational AI presents a mixed picture. The random control study showed that users of both voice modalities tended to have improved emotional wellbeing at the end of the study compared to users of the text modality. Better still, users who started with worse emotional wellbeing had improved outcomes at the end of the study when using the engaging voice modality over both the neutral voice and text ChatGPT.

On the other hand, the study of four million conversations showed that users of either voice mode were more likely to have conversations with emotion classifiers than users of text-only models. The researchers suggest that, compared to the random control study where users could not swap between text and voice modalities, “[t]his suggests that users who are seeking affective engagement self-select into using voice, driving the higher rates of affective cues in interactions observed in the wild”.

So, humanlike AI is a challenge, but in complex and nuanced ways, which is hardly surprising given how complicated imitating the humans AI can be.

Peter Waters

Consultant