The European Commission has just released the final version of a code of practice for general-purpose artificial intelligence models (for example, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude and Mistral’s Magistral). The code is voluntary, but developers who choose not to sign up to the code will have to demonstrate how other measures ensure compliance with the AI Act.

The code has three parts: transparency, copyright and safety.

Transparency

The rationale of the transparency obligations is that, because AI models form the basis of a wide range of downstream AI systems, developers have a “particular responsibility” to ensure that regulators and downstream providers (which fine tune or integrate the models) have “a good understanding of the models and their capabilities”.

The following table sets out key disclosure obligations of developers to the AI Office, national regulators (NRAs) and downstream providers (DPs):

Copyright

The code avoids directly addressing the issue of whether training infringes a human creator’s IP by essentially saying 'the law is whatever the copyright law says'.

The focus instead is on technology-based means by which creators can convey their non-consent to use of their works in AI training:

If developers or third parties on their behalf use web crawlers to obtain training data, they must employ state-of-the-art web crawlers that read and follow instructions on use of works inserted by the creator on their website (using robots.txt).

Developers must comply with any machine-readable protocols expressing rights reservations that comply with industry standards or are “widely adopted by rightsholders” in a cultural sector. This obligation has been strengthened from the third code draft which only required a developer’s “best efforts” to comply.

Developers must take reasonable efforts to ensure that creators can obtain information about the web crawlers used by or on behalf of the developer.

Developers must take reasonable efforts to exclude web crawling internet domains that are “recognised as persistently and repeatedly infringing copyright and related rights on a commercial scale by courts or public authorities". This obligation was diluted a little compared to the third code draft by inserting the threshold test that the offending third party site must have “persistently and repeatedly” infringed copyright.

While developers argue that AI models learn patterns across vast aggregations of individuals’ works, models appear to have a puzzling ability to produce almost exact copies of individual articles on which they were trained. As a result, the code requires that developers “implement appropriate and proportionate technical safeguards to prevent their models from generating outputs that reproduce [protected] training content".

On the output side, in a fairly slim measure to address copyright infringement by users, the code requires developers to include prohibitions against copyright infringement in their acceptable use policies. In the third Code draft, this obligation did not apply to open-source AI. However, the final version now provides that open-source developers must “alert users to the prohibition of copyright infringing uses of the model in the documentation accompanying the model” but that is “without prejudice to the free and open-source nature of the license”.

Safety and security

The safety and security requirements of the code apply only to AI models carrying “a systemic risk”.

The code drafters have seesawed on the definition of systemic risk. The final version of the code lists the following ‘identified systemic risks’:

development of chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear weapons

loss of human control over AI

cyber attacks

risk of manipulating human behaviour and opinion.

Initial drafts had also included infringement of fundamental rights (that is, human rights under the EU Charter of Rights), but the third code draft shifted fundamental rights from the core definition of systemic risk to a second ‘only if you find it’ category. The drafters explained that, as general-purpose AI can be used for a wide range of downstream uses beyond the direct knowledge of the developers, it is the downstream providers which should be responsible for applications that infringe human rights. Human rights and civil society organisations roundly criticised this approach as a ‘downgrading’ of fundamental rights.

In a typically EU approach, the final version of the code tries to split the difference. Developers have to assess their models for the list of identified systemic risks (which continues to exclude fundamental rights) but they also must compile “a list of risks that could stem from the model and be systemic” having regard to a broad set of listed factors. These factors include whether the risk increases with model capabilities and reach, the risk has significant social or economic impact, the risk can be propagated at scale across the value chain, the risk can materialise rapidly, potentially outpacing mitigations and the damage done is difficult or impossible to reverse.

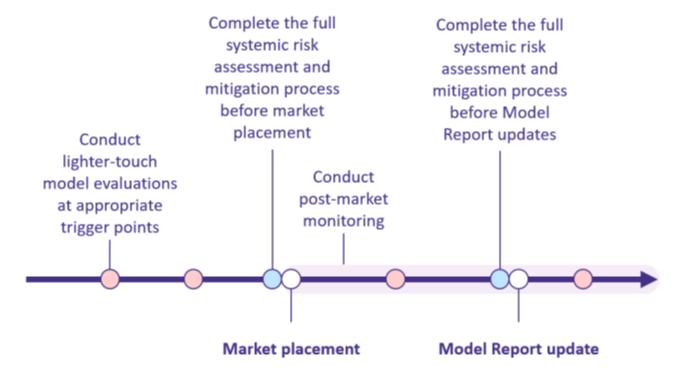

Developers of models with systemic risk are required to implement a safety framework which must be provided to regulators no later than two weeks after placing the model on the market. The framework is to be structured as follows:

There must be lighter-touch evaluations throughout the lifecycle of an AI model, from the initial conception, through development, training and post release, with the objective of building an ‘always on’ safety culture in developers.

The full-blown risk assessment immediately prior to market release must assess each systemic risk against pre-determined risk tiers; calibrate the extent to which mitigation adjusts the risk downwards; quantify the safety margin having regard to any previous gaps or limitations in model evaluations and the risk that safety mitigations could be circumvented; and then weigh these against the pre-determined criteria setting the overall level of acceptable risk for market release.

The risk assessment is not to assess risks of the model in isolation but needs to look to the wider context of what’s happening in AI development, including to factor in the following external developments:

Scaling laws that suggest novel ways of improving model capabilities (are bigger models safer?).

Novel architectures that improve computational efficiency or advance model capabilities.

Forecasts concerning the development of algorithmic efficiency, compute use, data availability and energy use.

Expert and lay opinion on the impact of AI on humans.

The code gives the following examples of safety mitigations that must be considered:

Fine-tuning the model to refuse harmful requests.

Phasing-in access, starting with API access for registered users and, after successful post-deployment monitoring, opening access to the wider public.

Putting risk mitigation tools in the hands of users.

Measures to support safe ecosystems of AI, such as model identification and secure inter-AI communication protocols.

Building in parameters which require models to disclose their chain of reasoning to help users better identify problematic responses.

The pre-release risk assessment also must include an independent external evaluation of AI models with systemic risk prior to release, other than in very narrow circumstances. The risk evaluation, the risk determination and the independent report must be provided to the AI Office.

Post-deployment of a general-purpose model with systemic risk, developers must conduct ongoing monitoring “to gather information relevant to assessing whether the systemic risk could be determined to not be acceptable and to inform an update to whether [the safety report to the regulator] is necessary”. The code identifies potential monitoring measures:

Channels for downstream developers, deployers and users to report major issues, including on an anonymous basis.

Bug bounties.

Community-driven model evaluations.

Monitoring software repositories, known malware, public forums and/or social media for patterns of use.

Implementing privacy-preserving logging and metadata analysis techniques of the model’s inputs and outputs, including data provenance tools (that is, for copyright infringement issues).

Post-release, the developer also must provide “an adequate number of independent external evaluators with adequate free access” to the model, including chains-of-thought of the model (but apparently not much further into the inner workings of the model access). Developers must not take any legal or technical retaliation against the independent external evaluators as a consequence of them acting in good faith in testing and/or publication of findings.

Finally, post-release, the developer must do a ground-up assessment of the adequacy of the risk framework every 12 months or sooner if there has been a report of a major fault.

Conclusion

The code must be adopted by the European Commission and Council, with time running out as the overarching AI Act authorising provisions are scheduled to commence on 1 August 2025. Compliance with new general-purpose AI models kicks in 12 months and for existing models in 24 months.

The EU is under heavy pressure to delay AI regulation and not just from the US-based Big Tech companies backed by the Trump Administration. Shortly before the code’s release, 46 major EU tech companies, including Airbus, Mistral, ASML and Mercedes-Benz, wrote an open letter requesting a two-year delay:

Europe has long distinguished itself by its ability to strike a careful balance between regulation and innovation…. Unfortunately, this balance is currently being disrupted by unclear, overlapping and increasingly complex EU regulations. This puts Europe’s AI ambitions at risk, as it jeopardises not only the development of European champions, but also the ability of all industries to deploy AI at the scale required by global competition… This postponement, coupled with a commitment to prioritise regulatory quality over speed, would send innovators and investors around the world a strong signal that Europe is serious about its simplification and competitiveness agenda.

The Commission’s spokesperson quickly responded:

I've seen, indeed, a lot of reporting, a lot of letters and a lot of things being said on the AI Act. Let me be as clear as possible, there is no stop the clock. There is no grace period. There is no pause.

Peter Waters

Consultant