Stanford University’s Human-Centered AI (HAI) unit has released its 2023 version of the Global AI Vibrancy Tool (GVT), a visualisation tool allowing comparisons of the vibrancy of the AI ecosystem across 36 countries.

Spoiler alert for Australians: we aren’t looking too vibrant.

Design of the GVT

HAI collected publicly available data on 42 AI-related factors grouped into the following pillars:

Innovation: R&D academic output, technological advancements and intellectual property generation.

Responsible AI: as a proxy for the level of national conversation on AI privacy, ethics and safety, the volume of conference submissions on these issues.

Economy: the level of private investment, AI job postings, net migration of people with AI skills and economy wide measures of AI skill levels in current workforces.

Education: the number of AI courses on offer, the number of AI articles published and the rate of citation of those articles by others.

Diversity: gender, ethnicity and socioeconomic diversity within the AI community.

Policy and governance: the frequency of mentions of AI in legislatures, enactment of AI-specific laws and the extent of national AI strategies.

Public opinion: as a proxy, the rate of AI mentions in social media and whether relatively positive or negative.

Infrastructure: computational resources, data availability and network connectivity.

The GVT totals the scores on these to provide a comprehensive picture of a nation’s AI vibrancy, on the basis that these factors fed into and off each other. For example, the GVT researchers comment:

Robust education ecosystems can provide a continuous supply of skilled professionals that can drive AI forward, while diversity within the AI community improves creativity and reduces biases. AI solutions that are less biased can be more effective and equitable. Robust policy and governance frameworks provide the necessary support and direction for AI development.

Daylight between the US and the rest of the world

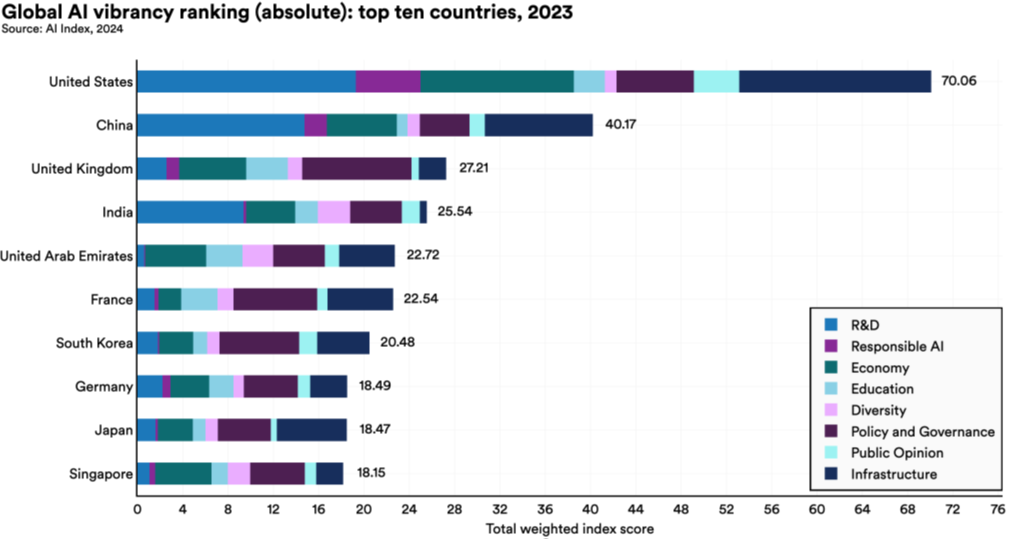

The following graph depicts the top 10 countries:

The United States leads the 2023 ranking by a significant margin, with its overall score of 70.06 being 175% of the overall score of second-placed China and 250% of third-placed UK.

The US dominates across almost all the GVT’s measures, including its R&D ecosystem, advanced computing and communications infrastructure, the skills of its labour force and active policy and governance frameworks. The US outpaced China in private investment, reaching $67.22 billion in 2023 compared to China’s $7.76 billion and the produced 61 notable machine learning models in 2023 compared to China’s 15 models.

China has substantial strengths in R&D, economy and infrastructure. In 2023, China led the world in AI journal and conference publications and registered three times as many AI patents as the US.

The UK has particular strength in the R&D, education and policy and governance pillars.

Three other key takeaways are:

The US is extending its AI lead over every other economy. The US lead over China has grown by nearly a third since 2021.

The GVT researchers note “population and geographic scale are not the sole determinants of AI vibrancy”, with the top 10 including United Arab Emirates (5th) and Singapore (10th). When the GVT metrics are set on a per capita basis, Luxembourg, Ireland, Sweden, Finland and Switzerland leap into the top 10. However, demonstrating the scale and depth of its dominance, the US on a per capita basis is at number 3, while China drops to 30 out of 36.

Outside the big two AI economies (US and China), the scores of other economies are closely grouped: for example, Japan is in 8th place with a score of 19.25 while Malaysia is in 26th place has a score of 13.51.

Australia

Unpacking Australia’s overall 28th ranking:

On the AI innovation subindex, Australia drops down a notch to 29th, behind Canada (9th), Denmark (13th), Singapore (18th), Finland (19th), New Zealand (21st) and Saudi Arabia (28th), and ahead of Russia (31st), Estonia (32nd) and South Africa last.

On the AI economic competitiveness sub-indice, Australia slips another notch to 30th, this time ahead of France (31st), New Zealand (32nd) and Brazil last, but behind the United Arab Emirates (5th), Singapore (6th), Denmark (14th), Canada (16th), Saudi Arabia (22nd), Turkey (23rd) and Malaysia (28th).

On the AI policy, governance and public engagement subindices, Australia soars to 12th place, not far behind South Korea (4th) and France (5th), and ahead of Germany (17th), Singapore (19th), Sweden (23rd), Canada (26th), New Zealand (35th) and South Africa last again.

This starts to paint an interesting picture: that is, 12th in AI policy and governance, but 29th in innovation and 30th in competitiveness – are we focusing on the wrong things? The world leaders in AI, being the US, China and the UK have all essentially adopted a pro-innovation approach to AI policy and governance, and it is paying dividends.

Australia does poorly by comparison with similar economies:

Of the 28 high income economies in the GVT database, Australia is third last overall, only ahead of Estonia and New Zealand.

Being a mid-sized economy is also not much of an excuse. When the GVT tool is reset to per capita rankings, Australia comes out in the middle of the pack: 16th overall, 15th on the innovation subindex, 20th on the economic competitiveness subindex and again uplifted overall by a better performance on policy and governance, at 9th.

The gap between Australia’s performance and better performing similar economies is more significant than its table ranking might suggest. The scoring behind Australia’s overall per capita 16th place ranking is only a quarter of Luxembourg’s (1st) and Singapore’s (2nd), half of the United Arab Emirates’s (4th), Finland’s (5th) and Ireland’s (6th), and three quarters of Denmark’s (12th) and Canada’s (13th).

The following table sets out Australia’s ranking on individual factors on a per capita basis:

Performance factor | Ranking (per capita) | |

Education sector | ||

AI articles published | 5/36 | |

AI articles cited | 3/36 | |

AI patents granted | 7/35 | |

AI study programs | 8/34 | |

Government / public discourse | ||

AI mentions in legislative proceedings | 4/32 | |

National AI strategy presence | 16/36 | |

Social media share of voice on AI | 7/36 | |

AI-related social media conversations net sentiment (higher ranking is more positive sentiment) | 20/36 | |

Labour market | ||

AI job postings (% of total) | 7/14 | |

Net migration inflow of AI skills | 11/25 | |

AI skills penetration | 20/24 | |

Investment | ||

Total AI private investment | 16/34 | |

Newly funded AI companies | 16/34 | |

Infrastructure | ||

Compute capacity | 16/27 | |

Internet speed | 22/35 |

The following conclusions can be drawn from the above GVT data:

Australia is good at the talk (legislative and social media mentions) but not so good at the walk (AI investment and AI skills). At the public level, most of this talk about AI seems to be more negative than in other countries. At the government level, despite our parliamentarians talking about AI almost more than any other legislators (or maybe because of it), and according to this index at least, leading the world on a National AI Strategy presence (on an absolute, not per capita basis) we still lag at the back of the pack on innovation and competitiveness.

Australia’s tertiary education sector (AI publications, AI courses and AI patents, which are likely to come out of university research) is performing much better on AI than the rest of the economy. However, we need to ensure we have the structures and environment to retain those skills and resources in Australia.

Australia’s private investment record in AI is at best average. We need to do better.

Australia also needs to focus on further skill development and infrastructure capable of supporting AI innovation and deployment. Australia’s AI skills base is underweight, but our performance would be worse without the net intake of AI skilled migrants. Our telco infrastructure is even more poorly performing. The GVT cover paper says of the importance of infrastructure:

Robust infrastructure is a critical prerequisite for advancing AI research…Countries with superior data centres and cloud infrastructure gain a significant advantage in conducting large-scale AI experiments. Moreover, the quality and quantity of available data sets vary widely between nations, directly impacting their ability to develop accurate and generalisable AI models. Network connectivity further amplifies these disparities. Nations that possess faster and more reliable internet connections can more quickly process real-time data.

Compared to 2022, Australia has gone backwards or trod water on most indices: for example, we fell from 8th to 16th in private investment, 15th to 20th in AI skills penetration and 17th to 20th in public sentiment on AI. The exceptions were a modest improvement in education criteria and a leap in governance from 15th to 9th, probably mainly due to the activities of Industry Minister Husic.

Conclusions

The recent buzz around DeepSeek provides a light post for Australia. While we certainly need more, we do have some excellent AI skills and resources, and there is opportunity to better invest in an exploit those skills, and convert skills and ideas to home grown commercial products on the international stage.

The Australian Treasurer has directed the Productivity Commission to undertake a wide-ranging study into improving Australia’s productivity, one pillar of which is the digital economy. Minister Husic has announced a separate inquiry into Australia’s research and development performance. This is a start, but more is needed.

The Tech Council has recently warned that we have to act now or risk Australia falling behind in AI development and adoption. The Tech Council urged co-ordinated government and private sector action on 6 fronts: TCA Statement on the Government's National AI Capability Plan - Tech Council of Australia.

uplift workforce, education and training

invest in critical infrastructure and assets

catalyse AI investment and adoption

attract and support breakthrough AI research

enable pro-innovation regulatory environment

enhance international engagement

This list hits Australia’s weak spots identified in the GVT.

Peter Waters

Consultant