In a follow-up to our previous analysis on copyright and AI training, we shift focus on a different question raised in the same EU Parliamentary report (Dr. Nicola Lucchi): should the outputs of generative AI be protected by intellectual property laws?

AI as an artistic tool

AI is rapidly reshaping the creative industries. Recent examples include:

Composers Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst used recordings of 15 UK choirs to train choral AI models for an immersive audio installation at London’s Serpentine North.

In a recent article, Rolling Stone says that AI is a transformative tool available to filmmakers at every level and is leveling the playing field in filmmaking: “AI isn’t replacing this human touch; it’s enhancing it by making storytelling more accessible”. Filmmakers no longer need a $100 million budget or a major studio’s backing to build sets, hire armies of extras or fund special effects development, “all they need is a compelling story and a willingness to embrace new tools”.

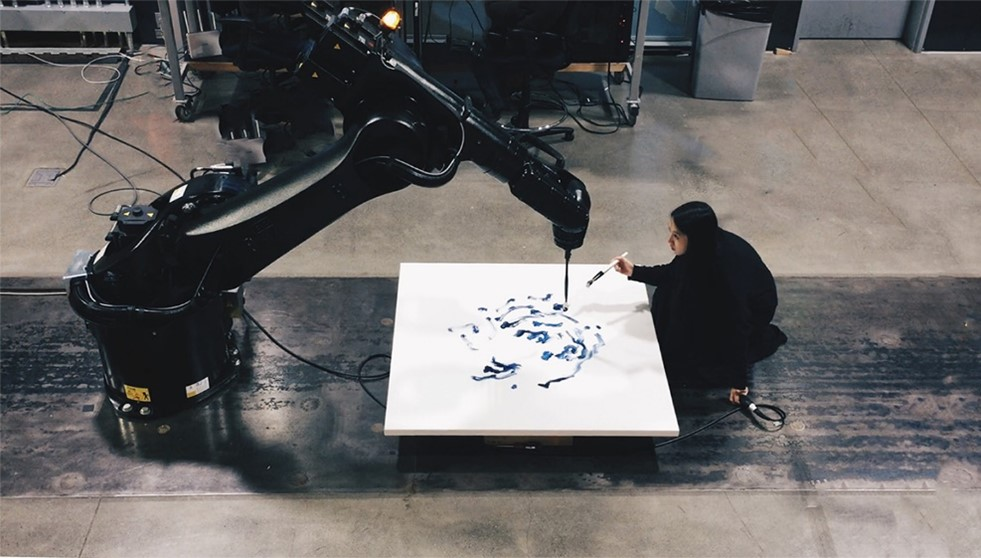

Artist Sougwen Chung explores human and machine co-creation in real time, pictured below painting with a robotic arm called DOUG (Drawing Operations Unit Generation).

AI’s capability to mimic human creative activities continues to rapidly evolve. For example, SketchAgent is a new drawing system from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) and Stanford University which teaches AI models to draw stroke-by-stroke. Existing text-to-image models such as DALL-E 3 can create images mimicking pencil or crayon hand drawings, but “they lack a crucial component of sketching: the spontaneous, creative process where each stroke can impact the overall design”.

Artist Sarp Kerem Yavuz argues that AI is no more the enemy of art than the computer or camera before it. Back in 1985, Andy Warhol used an Amigo 1000 home computer to digitally ‘screen print’ a photo of Blondie singer Debbie Harry.

However, AI is different: as the EU Parliamentary report observes:

Unlike traditional software tools, which follow rule-based instructions, GenAI models operate through probabilistic reasoning and data-driven generalisations. As such, they do not merely retrieve or remix existing content, but produce statistically derived outputs that resemble new forms of expression, modelled on prior data exposure. This fundamental shift in machine capability – from automation to generation – raises other questions for intellectual property frameworks, particularly in relation to authorship, ownership and originality.

In other words, does the insertion of ‘machine-generated creativity’ between the human and the output mean the human is no longer to be regarded as the creator or author of the output? If so, are there any IP rights in the AI output and who holds those rights – the AI model developer or maybe even the machine itself?

Copyright is for humans only

Many copyright laws, including in the EU, the US and Australia, are built on the foundational principle that legally protected creative expression is a uniquely human attribute and only the works of human authors deserve protection. As creators increasingly take up AI, what is the nature and degree of human involvement required for the creator to claim copyright in the output?

At one end of the spectrum are AI-assisted human works, where AI supports but does not replace human creativity. For example, a photographer may use AI as a post-production tool to adjust lighting conditions.

At the other end of the spectrum lie AI-generated outputs that are predominantly or entirely AI-generated. In a 2023 Czech case, a user created an image from a text-to-image prompt “create a visual representation of two parties signing a business contract in a formal setting, for example in a commercial room or in a law firm office in Prague. Show only the hands.”

The court reasoned that since the human operator had not made any creative choices in the expressive form of the image (for example, composition, colour, shading) and the AI system had assembled the output based on its training data and internal rules, the work was not considered eligible for protection. Prompts are more like ideas, in which there is no IP, than they are to expression, which can be IP protected.

As the EU Parliamentary report observes, the challenge is that “many creative workflows increasingly involve iterative human-AI collaboration, where human actors experiment with prompts, select from multiple outputs, provide feedback and perform extensive post-processing”. Even if the human does not touch the output, there could still be a meaningful level of human involvement and creativity: crafting prompts (called prompt engineering) is itself a skill and embedding a seed in the first AI-generated image also allows the user to prompt a series of variations on that image, changing colours, repositioning images, changing perspectives and adding objects.

The EU Parliamentary report proposes that ‘creative control’ should serve as a guiding interpretive tool: Did the human author make free and creative choices that shaped the final expression in a meaningful way? If so, protection may attach – even if some elements were machine-generated.

The problem, of course, is that this is a question of fact and degree in each case. The EU Parliamentary report recommends regulators publish clear, non-binding guidelines to assist in assessing whether there is a meaningful level of human involvement, including factors such as:

The extent of human control over generation.

The presence of creative choices in editing, structuring, or curation.

The use of judgment in selecting or combining generated material.

The degree of revision or refinement applied.

Should AI output be legally protected?

The EU Parliamentary report argues that extending copyright protection to AI-generated outputs is much more than just another incremental development in the law to address technological change (like the camera), but would strike at the very foundations of copyright law:

The entire edifice of copyright law – built on principles such as the distinction between ideas and their expression, the requirement of originality and the legal notion of authorship – presupposes the involvement of a human creator.

An alternative approach could be to introduce a new IP right tailored to AI-generated content (a sui generis right) for which there is some precedent. Pre-AI, some jurisdictions introduced legislation protecting all computer-generated works, including artwork. For example, in the UK the author of a ‘computer-generated’ work is taken to be the person who undertakes the arrangements necessary for creation of the work (s 9(3) Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988). This is also similar to the way that ownership of copyright in films is determined.

This sui generis right could offer ‘thinner’ protection than traditional copyright. For example, it could apply for a shorter period, such as three years, and it could be more limited in scope – for instance, only preventing literal copying, allowing subsequent human creators a permitted scope to adapt AI-generated works.

The key issue with a sui generis approach is “who is the creator?” The UK case Nova Productions v Mazooma Games concerned the ownership of copyright in frame images generated by a computer program using bitmap files and displayed on the screen when the users played a snooker videogame. The court refused to grant authorship to the user as their input was not artistic in nature. Instead, the court found the programmer to be the sole author and owner because “[t]he arrangements necessary for the creation of the work were undertaken by [the developer] because he devised the appearance of the various elements of the game and the rules and logic by which each frame is generated and he wrote the relevant computer program”.

However, it is less clear that the AI model developer should hold any similar rights in AI output. The output of an AI model results, on the one hand, from the data on which the AI was trained, for which the AI developer may not be responsible (depending on whether or not the model has been fine-tuned) and on the other hand, from the user’s prompt, as simple or as complex as those instructions may be. It is argued in the EU Parliamentary report that allocating rights in AI-generated output to the user of the generator program would be the fairer solution.

As it is the AI which generated the output, perhaps it should be recognised as the creator or author? However, as IP experts Enrico Bonadio and Luke McDonagh comment:

This may appear, at first sight, to be a fascinating and imaginative scenario – yet, it is unlikely to materialise, especially with respect to recognising the legal rights of AI/robots. The first strong (and obvious) objection is that machines, computers and robots lack legal personhood and therefore are not entitled to claim any legal rights including copyright. Giving AI/machines/robots legal rights would require, ex ante, answering complex questions about agency, whether machines should be considered not as mere products but as employees or agents; and that would necessitate a further assessment of liability issues (in relation to possible violations of rights of others committed by machines).

It is also inconsistent with the centrality of human authorship and creativity to copyright subsistence.

Underlying this debate is a more fundamental policy question of why would we protect AI-generated content at all: just because AI can generate novel content in a convincing imitation of human creativity, why should that content be afforded protection like human expression?

The EU Parliamentary report gives the following reasons for not specifically protecting AI-generated content:

Granting IP-like rights to machine-generated outputs (granting ‘a monopoly over abundance’) risks introducing a flood of cheap-to-produce AI-generated content that would devalue genuine human creativity and undermine the economic viability of professions in the cultural and creative sectors.

Recognising IP in AI-processed outputs would harm the public domain. Vast quantities of AI-generated material, lacking human authorship, could enter protected status – enclosing algorithmic recombination of existing cultural material. This could stifle innovation, restrict access to knowledge and erode the digital commons. By contrast, treating non-human outputs as unprotected helps enrich the public domain, promoting remix culture, innovation and access.

The incentives of developers and distributors of AI models are already adequately protected through IP protection in the underlying software, patents, trade secrets and competition law without granting IP rights in AI outputs.

Anchoring copyright in human creativity provides normative clarity in a fast-changing technological environment, in line with the foundations of European (and international) copyright doctrine. This is appropriate if the EU refines how it operationalises existing principles to address the emerging grey zone between human-augmented and machine-driven creativity, by developing robust guidelines as noted above.

Conclusion

While the EU Parliamentary report makes powerful arguments for human creativity remaining the foundation of IP rights, it also acknowledges that debate over the attribution of authorship in hybrid human-AI creations is likely to intensify as generative AI systems evolve. The imperfect analogy of AI to a painter’s brush or camera is already fraying. An Oxford University report on the impact of AI on art practice says that working with AI models, “involves balancing heightening surprise with the frustration of having less control over one’s medium”. As one artist explained:

It’s cool when the network misinterprets things and gives you surprising results, but it’s also very frustrating when you cannot get the exact image that you want. I feel like I have a lot less control over the exact thing that I’m making. It’s not like I’m a painter where I can just place a brushstroke wherever I please. I’m working with a larger system. If I had to describe working with algorithms, I’d have to say it’s a split between frustration and nice surprise all the time.

As Dilan Thampapillai points out:

What is missing here is the threshold event that would give rise to a paradigm shift in our thinking about AI. That is, a technological development has yet to occur that would represent a tipping point wherein AI moves from being a mere tool to being something akin to the master, thereby comprehensively replacing a substantial tranche of human labour. In the absence of such an event or development, the argument for extending copyright protection to works of nonhuman authorship is somewhat speculative.

Peter Waters

Consultant