Welcome to the second instalment of our snapshot series on the social and affordable housing sector.

In our last snapshot article we discussed the challenge of where to locate social and affordable housing (SAH) hubs and how housing providers, builders, funders and governments at all levels can understand and overcome the challenges faced in this selection process through the use of artificial intelligence.

In this instalment, we will examine another challenge for SAH projects in Australia – sourcing and structuring the funding required for such projects. To deliver SAH projects at scale, community housing providers (CHPs) typically need both senior and subordinated (that is, institutional) capital. Typically, a SAH project will consist of senior debt (representing anywhere between 70% – 80% of the capital structure) and the remainder of the capital required for the project will be funded by subordinated debt (representing anywhere between 20% - 30% of the capital stack). Other sources of capital can also include government grants or concessional loans where appropriate.

While SAH projects can often source senior debt (through concessional loan funding from Housing Australia or from commercial banks), for CHPs and project sponsors, often the bigger challenge is locking in funding for the subordinated / institutional component. The costs and complexities involved in financing this component can be high and it can drive approach to the broader structure and timing of a project.

To understand why implementing the subordinated debt component in a project’s capital stack is complex, it is important to understand why a SAH project requires subordinated debt in the first place. Why not pure equity?

This is due to the inherent ownership structure of CHPs, which are typically not-for-profit / charitable organisations incorporated as companies limited by guarantee (that is, there are no shares held in CHPs). This means that lenders cannot take share security over the project vehicle like in a more traditional project financing. Because there are no shares held in a CHP, profits can only be distributed back to project sponsors / investors by way of repayment of their subordinated debt, meaning subordinated lenders must negotiate complex intercreditor arrangements with other debt providers in the capital stack (senior debt, grant funding and/or concessional loans).

The building blocks: Key components of subordinated debt

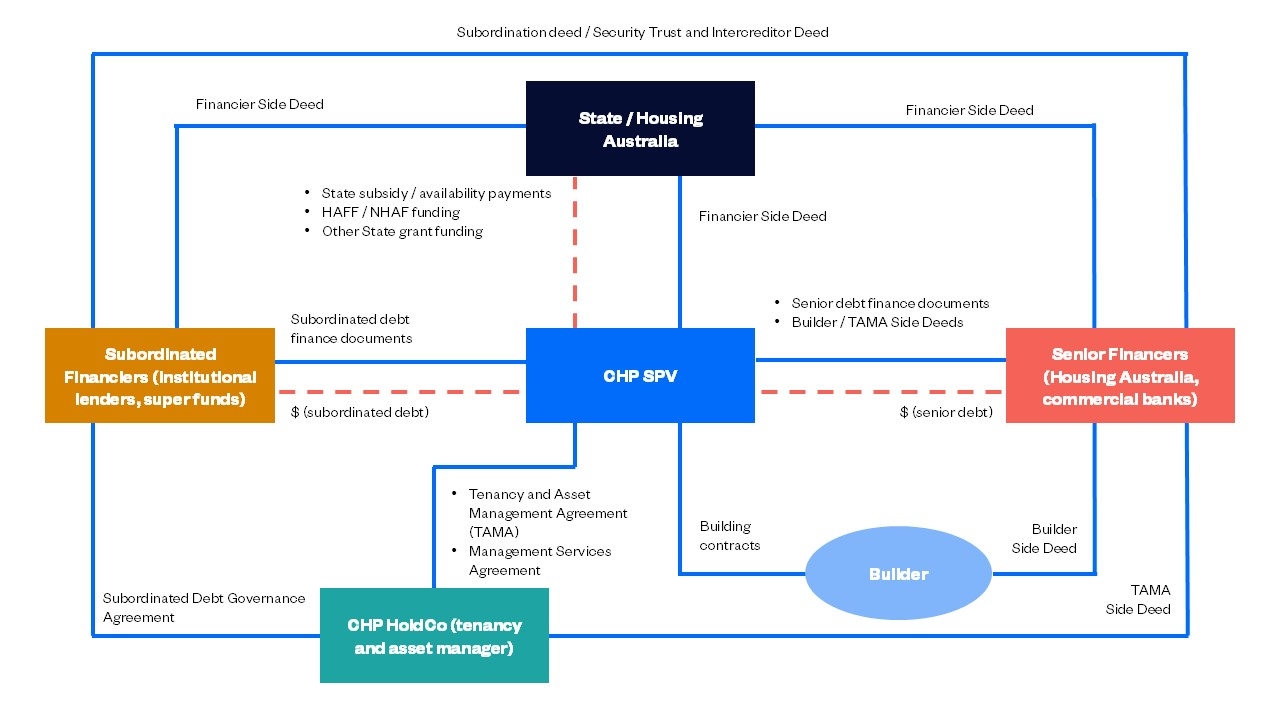

The following diagram shows a simplified funding structure for a typical SAH project.

SAH structure funding commentary:

Senior debt financiers provide between 70% - 80% of funding.

Subordinated debt institutional financiers (e.g. superannuation funds) provide between 20% - 30% of funding. Timing of subordinated debt injection varies. Increasingly subordinated debt is back-ended with equity support letters of credit / bank guarantees provided upfront.

Due to the ownership structure of CHP borrowers (no shares are issued by the CHP borrower), the only way profits can be distributed to the project sponsors / investors is via repayment of the subordinated debt loan.

Preconditions to the repayment of subordinated debt loans are similar to that seen in PPP funding transactions (meaning that subordinated debt can only be paid from funds available at the ‘bottom’ of the cashflow waterfall and only if certain distribution conditions are satisfied, including that financial covenant levels have been tested and maintained).

Subordinated debt is deeply subordinated and assumes equity-like risk (including financing, development, construction, and operational risk), so will need to be afforded an economic return that is commensurate with that risk.

Typically, any grant funding provided by the State will be subordinated to the subordinated debt in all respects (both in priority of payment and security ranking, if secured).

With regards to any funding under the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) and National Housing Accord Facility (NHAF), any concessional loan provided by Housing Australia will typically be subordinated to the subordinated debt.

Side deeds are negotiated and agreed between various parties to manage contractual termination and step-in rights, including:

i. Builder side deed between the builder, the CHP SPV, and the senior financiers;

ii. Tenancy and asset management agreement side deed between the CHP SPV, the CHP HoldCo (tenancy and asset manager), and the senior financiers; and

iii. Side deeds between the State / Housing Australia, the CHP SPV, the senior financiers, and the subordinated financiers.

Key challenge - Returns and cost of subordinated debt

For many social and affordable housing projects, often an initial hurdle is to ensure that the investment return and economics of any deal are appropriate to facilitate the investment of private/institutional capital into community housing.

Investment returns for subordinated debt providers can be a challenge when they are looking to invest into SAH projects because of:

the deeply subordinated nature of their instrument (akin to equity); and

the relative long-term investment horizon (subordinated debt usually needs to wait 20 – 25 years to be repaid in full, after all senior debt is repaid and the State / Federal subsidy / availability payment ends).

Institutional investors often expect (understandably) higher returns to make their investment viable, comparable to other more traditional asset classes they could be investing in, such as commercial real estate and other more traditional social-infrastructure projects (schools, hospitals etc).

Conversely, inherent to any SAH project is a need for CHPs to keep financing costs as low as possible – as higher financing costs invariably creates a barrier for project viability. Ultimately this costs the taxpayer, as the quantum of government subsidies paid by State or Federal Governments to a CHP is typically sized according to the level of senior and subordinated debt in the structure.

One solution: Rethinking economics and encouraging investment from superannuation funds

While investing in SAH projects may not be an attractive proposition for some institutional investors given the relative long-term investment horizon, SAH projects offer a stable and reliable return given that they are backed by a government subsidy (or other forms of government funding). Such stability, coupled with other mitigating factors like investment in a diversified portfolio across different regions and a reliable inflation hedge, should encourage more institutional investors, and in particular, superannuation funds, to invest in the sector.

Recently we have seen a greater willingness from institutional investors / superannuation funds to invest in SAH projects. This can align with their interest in supporting social and community projects where this coincides with the investment objectives for the relevant investment options and the best financial interests of their members. We see this as an emerging trend as the Australian superannuation industry looks to more direct investments in domestic infrastructure assets.

Another solution: More innovative debt structures

CHPs are also beginning to think of innovative and collaborative ways to bring down the cost of subordinated debt by pooling together resources to raise more cost-effective debt on a group basis. Such initiatives aim to raise funds from debt markets to then on-lend to CHP project vehicles at fixed rates and “on a cost recovery basis”. The aim is to make SAH projects more economically viable, both for CHPs and State and Federal governments, by reducing the core costs of the project.

Other initiatives include funding structures that involve funding developers in the initial construction phase which then reduces construction risk for long-term financiers.

The key solution: Collaboration

The SAH sector plays host to various stakeholders (institutional investors, CHPs and government) working alongside each other, often for the first time. Each has its own specific goals:

institutional investors and superannuation funds are primarily focussed on ensuring that their rate of return meets the expectations of their investment partners and, in the case of superannuation funds, is consistent with the return and risk objectives for the relevant investment options;

CHPs are focused on providing and maintaining quality SAH and delivering supportive services to residents and tenants; and

governments are driven to increase the supply of housing given the political mandate to do so and the economic benefits that flow through the rest of the Australian economy from safe and reliable housing.

Given these diverse objectives, collaboration between the stakeholders is imperative to deliver SAH projects in a timely manner and at scale, and scale is what is needed to propel the sector forward.

While CHPs are best placed to deliver on the tenancy & asset management services and overall project management, this does not mean that subordinated debt providers and senior lenders should not have any control or say in how a project is developed and operated. Subordinated debt providers will need to have a say on significant matters, especially those which may negatively affect their returns.

For example, they will need to have a say on any material deviation from the existing financing and project document package and will need to have input on any cure plans developed with government in the event of a breach under State subsidy documentation. Appropriate governance arrangements between the CHP and the subordinated debt provider are necessary to address such fundamental issues, with an overlay of control from senior lenders on critical development and operational cost components.

The conclusion? Unlocking potential

When government, senior lenders, institutional investors and CHPs align their efforts, the path to delivering more SAH projects at scale becomes clearer and more efficient. Each stakeholder, by leveraging their unique strengths and expertise, plays a vital role in this collaborative ecosystem. By prioritising innovative funding solutions and embracing strategic partnerships, the sector can achieve enhanced returns for investors while maintaining project viability. Ultimately, this collective approach maximises the impact for those who need housing the most, ensuring that these initiatives not only meet financial and political objectives but also fulfill their social mission too.