The Australian Government’s economic reform roundtable begins this week with a focus on AI and employment. The peak union body, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), has warned that employees will not embrace AI if their key concerns are not addressed.

The ACTU is urging employers to guarantee job security for workers before introducing AI into their businesses. ACTU assistant secretary Joseph Mitchell presented this proposal in direct response to an interim report from the Australian Productivity Commission (APC) released the same day.

The APC’s interim report says that productivity growth from AI should rely on existing legal frameworks, with AI-specific regulations considered only as a last resort. The report suggests pausing current efforts to implement mandatory guardrails for high-risk AI. In contrast, the ACTU wants the Government to pass legislation that would bar the use of AI in businesses “that cannot reach agreements with their employees”.

Recent studies are shedding light on what workers want from AI and whether the technology’s capabilities align with those expectations.

The split between augmentation and automation

An early 2025 study by Anthropic researchers (Handa, Tamkin et al) matched 4 million ‘privacy preserving’ Claude AI conversations with US Department of Labor occupation categories, which the researchers say allowed them, unlike with previous studies, to “track the dynamic relationship between advancing AI capabilities and their direct, real-world use across the economy”.

The Labor Department database includes a list of primary job tasks which define each job category. For example, tutors and archivists in the education and library sector need to design and develop comprehensive educational materials, teach and instruct in diverse educational settings and manage and document publishing processes.

The study found that:

Use of AI is already widespread across the economy: 36% of occupations use AI in at least 25% of their job tasks.

The rate of occupational usage of AI is highly skewed: only 4% of jobs use AI for 75% of tasks and only 11% use AI for 50% or more of tasks. The researchers comment that “[t]his distribution suggests that while AI could be touching many occupations today, deep integration across most tasks within any given occupation remains rare for now”.

The highest AI use for tasks unsurprisingly is in software engineering roles and analytical roles (for example, data scientists), but AI usage is also high in professions requiring substantial writing capabilities (for example, technical writers, copywriters and archivists). Conversely, tasks in occupations involving physical manipulation of the environment (for example, anaesthesiologists, construction workers) currently show minimal use.

AI usage peaks in the upper quartile of wages, mainly driven by high paid technology-based occupations such as computer programmers and web developers. However, occupations at both extremes of the wage scale show limited usage. For example, waiters and anaesthesiologists are among the lowest users of AI.

Occupations requiring more extensive education and training qualifications tend to have much lower rates of AI usage. The researchers comment that “[t]hese results make clear that human barriers to entry may be significantly different than barriers to language models”, suggesting some degree of regulatory and/or self-protection among the more highly trained professionals.

The researchers observe that previous studies have identified whether job tasks are ‘AI exposed’ but have not said how AI is being or will be used in those tasks. The researchers identified from the nature of the tasks performed by Claude whether the model was automating the tasks (substituting for human labour) or whether it was augmenting human capabilities.

The researchers found that 57% of AI responses were augmentative and 43% involved automation. However, they noted that the level of augmentation could be higher, as users are likely to modify offline the AI-generated response.

What employees want of AI

A recent Stanford University study (Shao, Zope et al) asked 1,500 individuals across 104 occupations about their views on AI in the workplace. This study also used the same US Department of Labor job classifications to test employee attitudes to AI use at the level of individual tasks.

The study found that for 46.1% of tasks across the economy, workers currently performing them expressed a positive attitude toward AI usage, even after explicitly considering concerns such as job loss and reduced job satisfaction. Nearly 70% of workers said that AI would free up their time for more valuable work, nearly 50% said AI would improve quality and reduce task repetitiveness and 25% said it would reduce job stress.

However, employee preparedness to embrace AI is much lower in some sectors. For example, only 17.1% of tasks in the Arts, Design and Media sector received positive desire ratings, possibly reflecting the widespread sentiment among creative sector workers that AI is taking and mimicking their output without compensating them.

The study surveyed the depth of AI usage within their jobs with which employees would be comfortable using the following Human Agency Scale:

H1: AI agent handles the task entirely on its own.

H2: AI agent needs minimal human input for optimal performance.

H3: AI agent and human form equal partnership, outperforming either alone.

H4: AI agent requires human input to successfully complete the task.

H5: AI agent cannot function without continuous human involvement.

Surprisingly, 45.2% of occupations have H3 (equal partnership) as the dominant worker-desired level, underscoring the potential for human-agent collaboration. But workers also acknowledged that over a third of job tasks would fall into H2 (minimal human involvement).

The researchers compared how employees and AI experts rank occupations and tasks on the Human Agency Scale. AI experts tended to rank job tasks as requiring a lower level of human agency than the employees currently performing those tasks. The two groups aligned on only 26.9% of occupations. For example, editors were the only occupation where employees predominantly desire H5 (little AI involvement) while AI experts considered only mathematicians and aerospace engineers as falling into this category. At the task level, both employees and experts rank ‘interpersonal communication’ as essentially human-only (H5). Interestingly, the experts also add domain (subject matter) expertise in this category.

The study also found a significant mismatch between current AI commercialisation strategies and employees’ preparedness to embrace AI. By integrating the employee positiveness towards AI performing job tasks with AI experts’ assessment of AI capabilities to perform those tasks, the researchers identified four categories:

Automation “Green Light” Zone: Tasks with both high automation desire among employees and high capability assessed by experts. These are prime candidates for AI agent deployment with the potential for broad productivity and societal gains.

Automation “Red Light” Zone: Tasks with high capability assessed by the experts but low desire among employees. Deployment here warrants caution, as it may face worker resistance or pose broader negative societal implications.

R&D Opportunity Zone: Tasks with high desire among employees but currently low capability assessed by experts. These represent promising directions for AI research and development.

Low Priority Zone: Tasks with both low desire among employees and low capability assessed by experts. These are less urgent for AI agent development.

The researchers then assessed the activities of over 1,700 start-up companies (Y Combinator companies) across these four zones. They found that the AI products and services of 41% of these companies mapped to Low Priority and Automation “Red Light” Zone. The researchers conclude that this suggests “a misalignment between where investments are flowing and the joint perspective of both those developing the technology and the workers the technology shall aim to support”.

Instead of the tedious tasks, many AI tools target high-level strategy, marketing or client-relationship work; tasks that employees want to keep human. The result is bordering on farcical: employees groaning under 1,000 weekly copy-pastes and waiting in line for expense approvals, while startups chase sexy use cases. In fact, some studies point to around 26% of an office worker’s time being wasted on pointless tasks – roughly 76 days per year per employee…

Future work skills

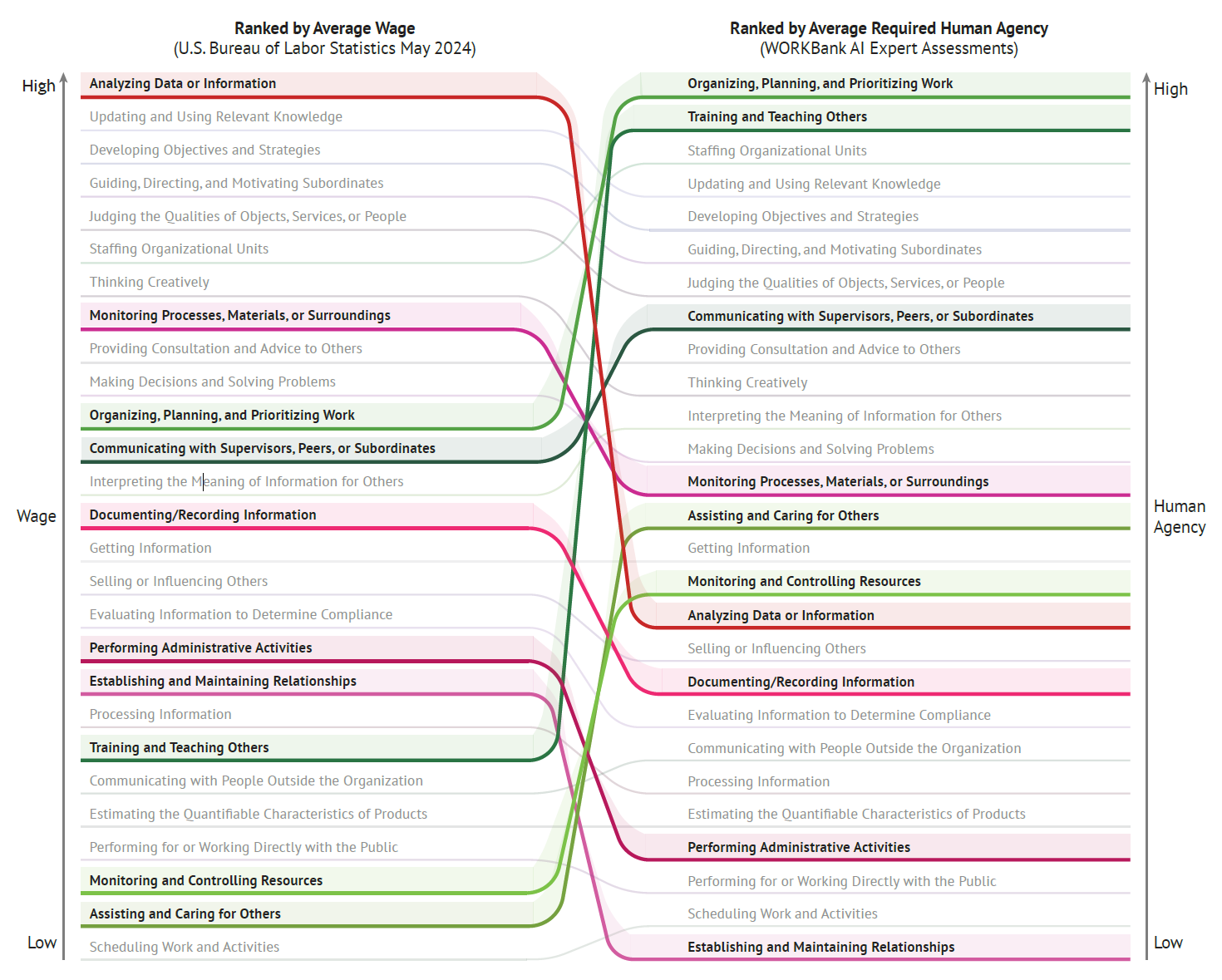

The Stanford study also compared the US Department of Labor ranking of skills currently attracting higher wages against the AI experts’ assessment of the skills required of humans as AI becomes more embedded in job tasks, as depicted below.

Source: Future of Work with AI Agents: Auditing Automation and Augmentation Potential across the U.S. Workforce, page 14.

The researchers conclude that as AI becomes more integrated into the workplace:

Data analysing skills, while common in today’s high-wage occupations, will decline substantially in demand and value.

By contrast, skills involving human interaction, coordination and resource monitoring will be more highly valued.

The top 10 skills with the highest average required human agency encompass a broad range, from interpersonal and organisational abilities to decision-making and quality judgment. This may demonstrate the continued gap between what AI and humans can do.

Conclusion

Much of the discussion around AI and employment has been on job losses: at one extreme, Elon Musk predicted that there would be no jobs in the future – AI will take them all, while at the other, some argue AI like past technology waves will create far more jobs than are lost.

The tension between these ideas can be seen in the very different positions being adopted by industry bodies. Business groups, especially in the financial sector, see AI as a major opportunity to boost productivity and move workers into higher-skilled roles. The APC's report estimates that AI will raise multi-factor productivity (MFP) by at least “2.3%...over the next decade, which would correspond to a 4.3% increase in labour productivity worth an additional $116 billion in GDP”. However, the ACTU is concerned to restrict the impact of AI on the existing composition of Australia’s workforce. It is now calling for a national AI authority and a whole-of-government approach to ensure the fair and coherent adoption of AI across industries.

In this polarised debate, sight can be lost of the complex impacts on job design, shifts in skills and efficient allocation of task sharing in an occupation between humans and AI – and employee perspectives of that. As Stanford says:

As AI systems become increasingly capable, decisions about how to deploy them in the workplace are often driven by what is technically feasible – yet workers are the ones most affected by these changes and the ones the economy ultimately relies on…Bringing their perspectives to the table is critical not only for ensuring ethical adoption but also for building systems that are trusted, embraced and truly effective in practice. It also helps reveal overlooked opportunities and guide more human-centered innovation, which in turn benefits technological development.

Peter Waters

Consultant