AI policy and regulation seem to be locked into a ‘winner takes all’ contest between advocates for AI innovation and those for AI safety. The pendulum seems to be swinging back from the EU AI Act, with France’s President Macron declaring at the Paris AI Summit in February 2025 that "[i]t's very clear [Europe has] to resynchronise with the rest of the world" by simplifying AI regulation.

Harvard’s 10 AI governance principles

In conjunction with the Paris Summit, the Future Society project at Harvard’s Kennedy School conducted the following structured process to investigate any emerging civil society consensus on AI governance requirements:

Step 1: in the lead-up to the Paris Summit, the Future Society, Make.org, Sciences Po, AI and Society Institute and CNNum conducted the global consultation, gathering input from more than 11,000 citizens and over 200 expert organisations across five continents.

Step 2: a workshop of 61 conference participants held on the margins of the Paris Summit identified governance gaps and submitted concrete proposals to fill those gaps. These were consolidated into 10 governance principles.

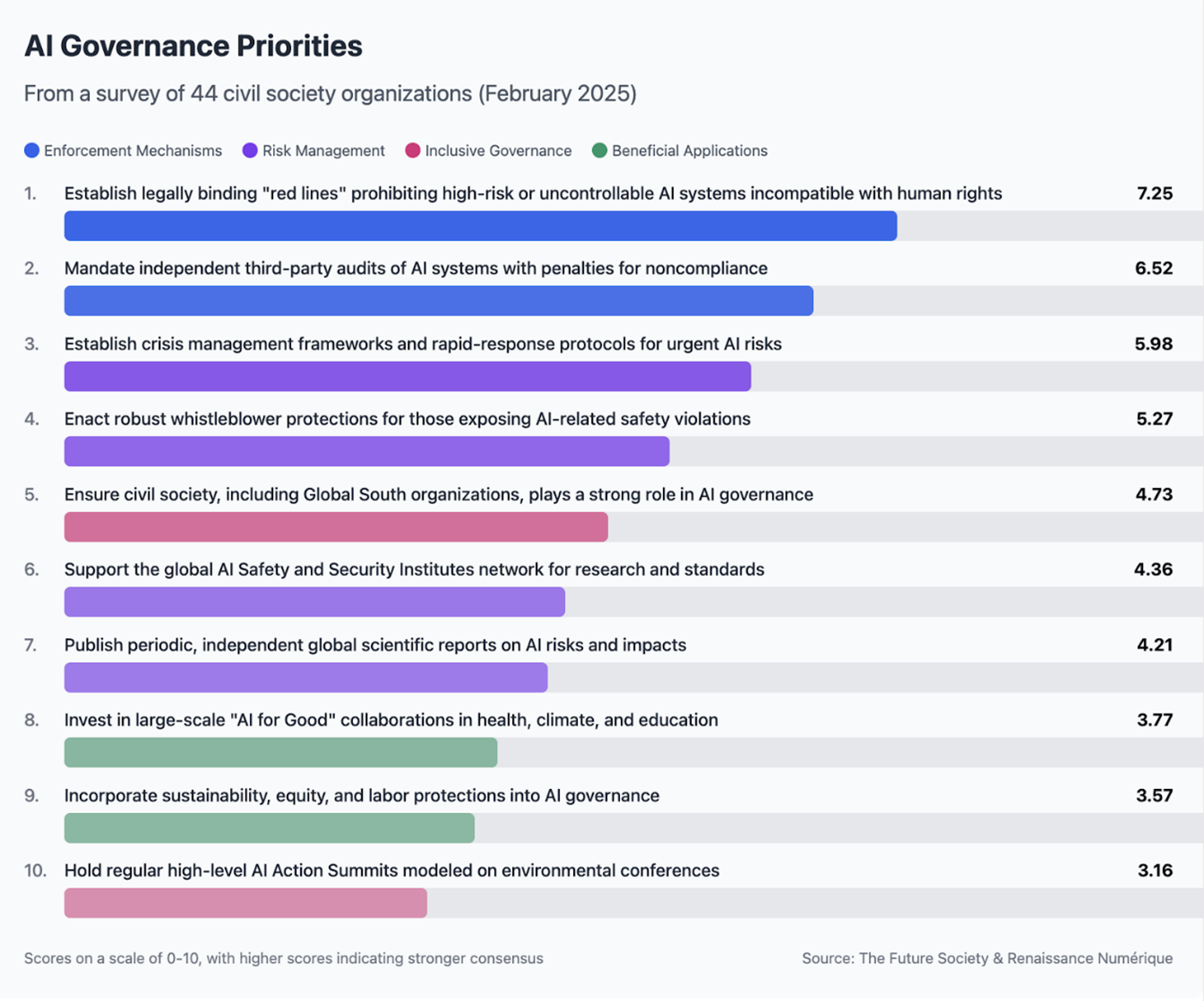

Step 3: following the summit, 44 civil society organisations globally – including research institutes, think tanks and advocacy groups – were asked to rank these ten potential governance mechanisms in importance.

The results are to inform the next AI Summit in India in late 2025.

While all ten options were identified as valuable through the consultation process, their relative importance was ranked as follows:

The Future Society then grouped the 10 principles into the following four focus areas:

Feedback from civil society groups on individual governance principles included:

The need for ‘red lines’: “AI governance developed without red lines to protect human rights and dignity would be a hollow sham.”

The need for external audits: “we must not allow AI companies to grade their own homework.”

The need for governments to proactively engage in risk management:

“Governments must increase focus on incident preparedness – the ability to effectively anticipate, plan for, contain and bounce back from incidents involving AI systems that threaten national security and public safety. This will require a range of measures, including updated incident response plans as well as ensuring there are appropriate legal powers to intervene in a crisis. If this does not become a priority now, we’re concerned that incidents could cause avoidable catastrophic harms within the next few years.”

The need for increased civil society participation to ensure more effective enforcement and risk management. The upcoming AI Summit in India will help focus on participation from the Global South in global AI regulation:

“AI is often built in contexts disjointed from their deployment. This geographical and resource disconnect creates a significant risk – AI systems developed in high-resource environments but deployed in lower-resource settings frequently produce unintended harms.”

The need for governments to lean into promoting the beneficial applications of AI:

“People today do not feel like AI works for them. While we work to minimise potential harms from AI use, we must also get concrete about prioritising progress on the things that matter to the public. This legitimacy gap could undermine support for governance itself if not addressed.”

South Korea’s new AI law

South Korea’s Basic AI Act passed earlier this year tries to integrate AI innovation and AI safety into a single legislative framework. While borrowing elements from the EU AI Act, it is less prescriptive and includes measures promoting AI development and use alongside developer and deployer responsibilities.

The Basic AI Act recognises the fundamental link between promoting AI innovation and uptake and public trust in AI. The government must undertake the following measures to build trust:

Forecast social, economic, cultural and everyday changes caused by AI use and improve relevant laws and institutions.

Support the development and dissemination of safety and certification technologies to ensure AI safety and reliability.

Educate and publicise safe and trustworthy AI society implementation.

Support the establishment and implementation of rules by AI business operators to ensure safety and reliability.

Support private activities, such as voluntary cooperation, creation of ethics guidelines and similar initiatives, by organisations comprising AI business operators and users.

The government must also develop an overarching National AI Ethics Framework which will set “the ethical standards that all members of society must observe in all areas related to the development, provision and use of AI, based on respect for human dignity and aimed at protecting people’s rights, lives and property to realise a safe and trustworthy AI society.”

The government’s industry development plans and all new laws and regulations must be assessed against the National AI Ethics Framework. All public and private sectors of the economy are encouraged to set up their own sector-specific ethics committees and the Minister for Science and Ethics is to issue guidelines to ensure these committees are balanced and neutral, hinting that civil society and consumer groups should be involved.

The Basic AI Act imposes a transparency obligation on all deployers of AI: they must disclose to consumers when AI is being used and explain how AI has been used in the determination of an outcome affecting the consumer.

Like the EU AI Act, the Basic AI Act applies additional obligations on developers and deployers of ‘high impact’ AI. The Act has a list of specified use cases which are categorised as ‘high impact’, including government decisions impacting citizens, transport, energy and other critical infrastructure, loan and financial assessments and analysis and utilisation of biometric information (facial, fingerprint, iris, palm, and so on) used for criminal investigations.

This list may be varied by Presidential Decree. However, unlike the EU AI Act, there is an open-ended category of high impact AI capturing any other AI models that significantly affect human life, physical safety and fundamental rights.

As with the EU Act, an AI business operator providing high impact AI must:

Develop and deploy a risk management plan.

Provide technical documentation on safety to users.

Ensure human oversight and supervision.

Ensure explainability of AI outputs.

Implement other safety measures required by the ICT Minister on recommendation of an industry-based safety committee and the AI Safety Institute.

Like the EU AI Act, the Basic AI Act also imposes separate obligations on the upstream developers of general-purpose AI models. The developers will not necessarily know how their AI models will be used and therefore the ‘high impact’ categorisation approach won't often capture these foundation models in the development stage. While the EU rules will apply only to those general-purpose AI models which present a ‘systemic risk’, the Basic AI Act requires all exceed a threshold of cumulative computational use for training, as determined by Presidential Decree, must:

Identify, assess and mitigate risks, including risks to fundamental rights, and report this self-assessment to the ICT Minister.

Implement a risk management plan in accordance with the requirements published by the ICT Minister.

On the innovation side:

A set of AI specialist bodies is to be established: a National AI Committee to consist of key industry and other stakeholders; a National AI Office to co-ordinate AI policy; and a National AI Safety Institute which is to work with safety institutes in other countries. Reflecting the twinned purposes of innovation and safety, the National AI Committee’s mandate includes promoting research and development of AI and uptake of AI products, but it also may require “national institutions” to develop plans to implement the National AI Ethics Framework for its approval.

Three-yearly National AI plans are to be developed by the Minister for Science and ICT, in consultation with a National AI Committee, to promote AI technology and the AI industry and to enhance national competitiveness. The National AI Plan must “secure resources and directions for investment in R&D and industrial promotion of AI technology” and “ensure fairness, transparency, responsibility and safety of AI and measures to build trust”.

The Minister of Science and ICT will develop standards for AI technology and related areas, such as training data, AI safety and reliability.

The Minister of Science and ICT will develop an AI skills and training program, including measures to attract overseas AI experts.

Measures are also to be taken to build a sovereign data capability for AI training, such as a national AI training library, for which the government can charge developers access fees. The intellectual property rights of creators are protected by the Korean Constitution.

Conclusion

Future Society makes the point that as AI capabilities advance rapidly, the window for establishing effective governance is narrowing. It acknowledges the challenge in doing so: “[r]eplacing aspirational principles with concrete, enforceable mechanisms remains essential to ensuring AI development proceeds in ways that are safe, beneficial and aligned with the public interest”.

While Future Society’s work distils high-level AI principles – and a gauge of an emerging civil society consensus on the key issues – a significant gap remains between these principles and the detailed drafting required for an effective AI law.

South Korea’s new law is an example of balancing the concerns between the AI optimists and the AI pessimists.

Next week we review the recent report of a California expert group advising the Governor on AI regulation.

Peter Waters

Consultant