Remote working is sometimes promoted as having the potential to be the ‘great equaliser’ of economic opportunity. In its pre-COVID form of ‘off-shoring’, remote work could help mitigate the divide in economic opportunity between the Global North and the Global South. Post COVID with remote working embedded as the ‘new normal’ in developed economies, it could help bring jobs to rural and regional areas, helping foster sustainable local communities by offering alternatives to the physical migration of young people to metropolitan areas.

However, a recent Oxford University study has found the opposite outcomes: remote labour market is a ‘digital mirror’ of the polarisation of economic opportunities between countries and between metropolitan and rural areas within countries.

Study design

The Oxford study involved a statistical analysis of nearly 2 million records of projects that were contracted on a global online outsourcing platform between 2013 and 2020. The researchers argue that online outsourcing platforms provide a good predictor of remote working in the broader economy because:

Due to the digital organisation of the hiring and work process on the platform, online labour markets can be considered as a prototype of a fully remote labour market. Having started as niche marketplaces for IT freelancers, these platforms now cover the whole spectrum of knowledge work, from data entry to management consulting, with millions of platform workers involved globally.

The number of globally registered online workers was 163 million in 2021.

The researchers asked themselves three questions:

how is remote platform work distributed between and within countries? What is the relationship between urban and rural areas?

are the unequal global distributions of remote platform work activity and wage differentials in Global North and Global South countries determined by local institutions, infrastructure and economic conditions?

how far are outcomes of different job types in the remote platform labour market (wage levels, value of experience) related to differences in competitive intensity and skill requirements across occupations?

To answer these questions, the researchers undertook regression analysis of the data along parameters that included national and, most uniquely amongst studies of remote working, sub-national data on population concentrations, education and skills levels, income and internet connectivity.

The North-South Digital Divide

The Oxford study looked at the country locations of the ‘buyers’ and ‘sellers’ on the online platform, covering some 163 countries or economies.

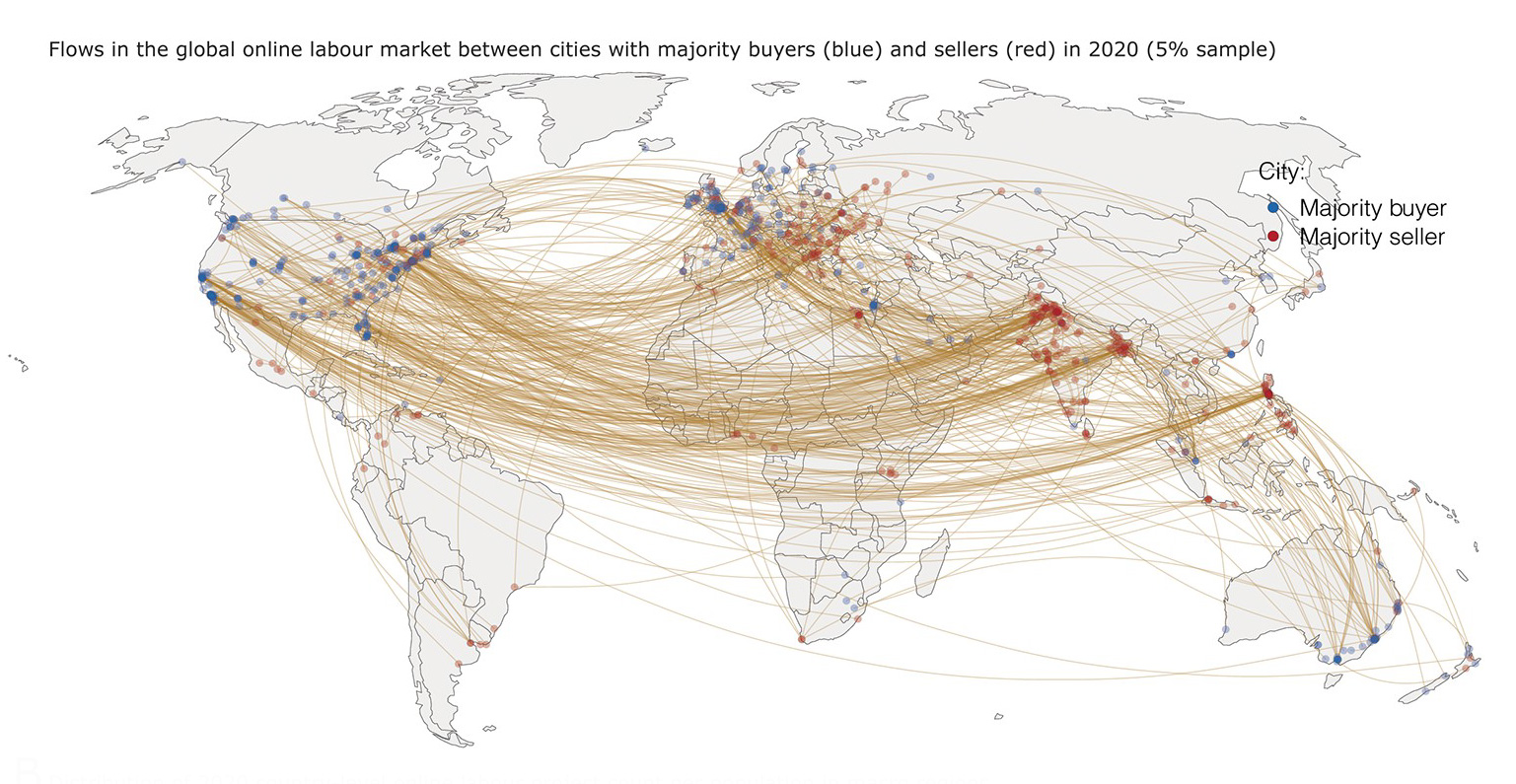

As the following map shows, there is a flow of economic activity from the Global North to the Global South, but demand and supply cluster in a limited number of places. Most demand comes from urban areas in North America, West Europe, and Australia, while most remote platform workers are located in East Europe, South Asia, and the Philippines. In fact, online workers in just five countries (India, Pakistan, Philippines, United States, Bangladesh) account for more than 50% of all online labour projects. The rest of the Global South largely misses out on global outsourcing of online projects.

The Oxford study also found a big gap between the project fees charged by online workers in the Global North compared to online workers in the Global South. While platform workers in the United States, United Kingdom, and Russia charged more than 30 USD per hour on average, remote workers in Bangladesh and the Philippines earned just 6 USD an hour. This, of course, would be expected as the cost differential is one of the factors driving outsourcing to the Global South, but as discussed below, the Oxford Study found the cost differential plays out in more complicated ways.

The Oxford study found some promising exceptions amongst Global South economies. Kenya and South Africa host relatively active platform worker communities. Kenya’s participation per population is comparable to that of the United States. Averages wages of South Africa’s platform workers are comparable to those in Europe.

The urban-rural divide within countries

By sorting the location of online workers into sub-national geographic levels, the Oxford study was able to compare participation rates between online workers located in metropolitan areas compared to other regional areas.

The researchers found that participation rates vary by two to four orders of magnitude in many countries. In the OECD+ (comprising OECD countries plus Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, and South Africa), the capital regions attract more than three times as many platform jobs per capita than other regions in the same county. The urban-rural divide is even more pronounced in the Global South, where capital regions obtain more than 15 times as many projects per capita as other regions in the same country.

Online workers in metro areas are also paid more than online workers in regional areas, earning on average 24% more per hour.

This leads the Oxford study to conclude that “platform work is a metropolitan phenomenon.”

What’s going on?

The regression analyses undertaken by the researchers strongly showed a number of mutually reinforcing factors.

The larger a region’s population, the more projects it attracts. Similarly, higher levels of education are associated with higher project counts.

The income level is negatively associated with project count on the global scale and in the OECD+, while it is positively associated in Global South regions. This indicates that it is middle income countries or regions that attract most remote jobs.

As would be expected, internet connectivity is positively associated with project count: the better the internet infrastructure, the more remote platform work.

At an individual worker level, workers need to send quality signals to demonstrate experience and trustworthiness to potential employers, such as ratings or reviews about past projects. Projects which require lower skills base have lower barriers to entry, more competitors and each worker has less projects they can use to send signals to employers. This sparks a race to the bottom: “without reputation, they find it hard to get their first job, so they need to undercut wages, leading to a vicious circle of more competition and lower wages.”

This dynamic also has a powerful urban/rural dimension:

If [remote workers] are unlucky not to be located near specialised industries or agglomerations, they are more likely to offer work in occupations characterised by easy-to-copy skills and fierce competition. In contrast, remote workers from metropolitan areas already have access to ample urban opportunities for knowledge exchange and local work opportunities, due to a bundling of complex economic activities and a more fine-grained division of labour in urban environments.

Hence, the Oxford Study concludes that, contrary to the promise that remote working could break down the geographic rigidities of the off-line labour market, these rigidities are deeply encoded into the online market. Actually, the Oxford study reckons things may be worse in the online market:

The polarising forces that pull remote jobs to centres of economic activity with existing competitive advantages and digital infrastructures work almost unrestricted in the platform economy. This is because there are only limited frictions of geographical boundaries, labour market regulations or formal entry barriers, which increase the role of information asymmetries, uncertainties, trust cues, and reputation systems in online labour markets.

The Oxford study confirms other studies that found online platforms were mainly used by ‘migrants’ to metropolitan areas: young workers who have left their rural and regional homes to urban areas because of better income opportunities - they just execute on those opportunities through online platforms while living in their new metro pads.

Policy implications

So remote working is not the antidote to the vexing economic tale of the ‘booming metropolis’ and the ‘broken provincial city’.

Governments still need to do the hard spade work in regional and rural areas to improve educational opportunities, facilitate ‘clusters’ of innovative businesses, and build the communications and other infrastructure needed to develop regional areas.

The difference pre- and post-COVID is that remote working shows that, if this ground work can be laid, value-enhancing, high skilled work can be done outside metropolitan areas, but it won’t achieve economic transformation by its own force.

However, it is not all bad news on the potential impacts on social inequality of remote working. US Department of Labor figures show that the participation rate of disabled workers has climbed by 5% since 2020. That seems largely attributable to disabled workers being able to work remotely from their home environment rather than navigate commuting and working in an office or factory not equipped to their needs.

Read more: University of Oxford | New Oxford study reveals remote work failing to bridge the urban-rural divide

KNOWLEDGE ARTICLES YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN:

The Legal 500: Blockchain (Australia)

Global Legal Insights: Blockchain & Cryptocurrency Regulation 2024