Last week, the European Commission released a 400-page report on the future of European competitiveness by Mario Draghi, former Prime Minister of Italy and President of the European Central Bank. The report confronts the challenge of changing global paradigms and Europe’s need to become more productive, having missed the digital revolution led by the internet and the productivity gains of the tech sector. Otherwise it will be condemned to the slow agony of its fundamental values of prosperity, equity, freedom, peace and democracy eroding.

The Draghi report recommends both sectoral (telco, energy, pharma, AI, and transport) and horizontal (innovation, skills, competition law, and EU governance) policies directed to ensuring the EU closes the widening gap with the US and meets the looming challenge of China. We review the report’s analysis of the digital sector and the role of competition law.

1. A four alarm fire in the digital sector

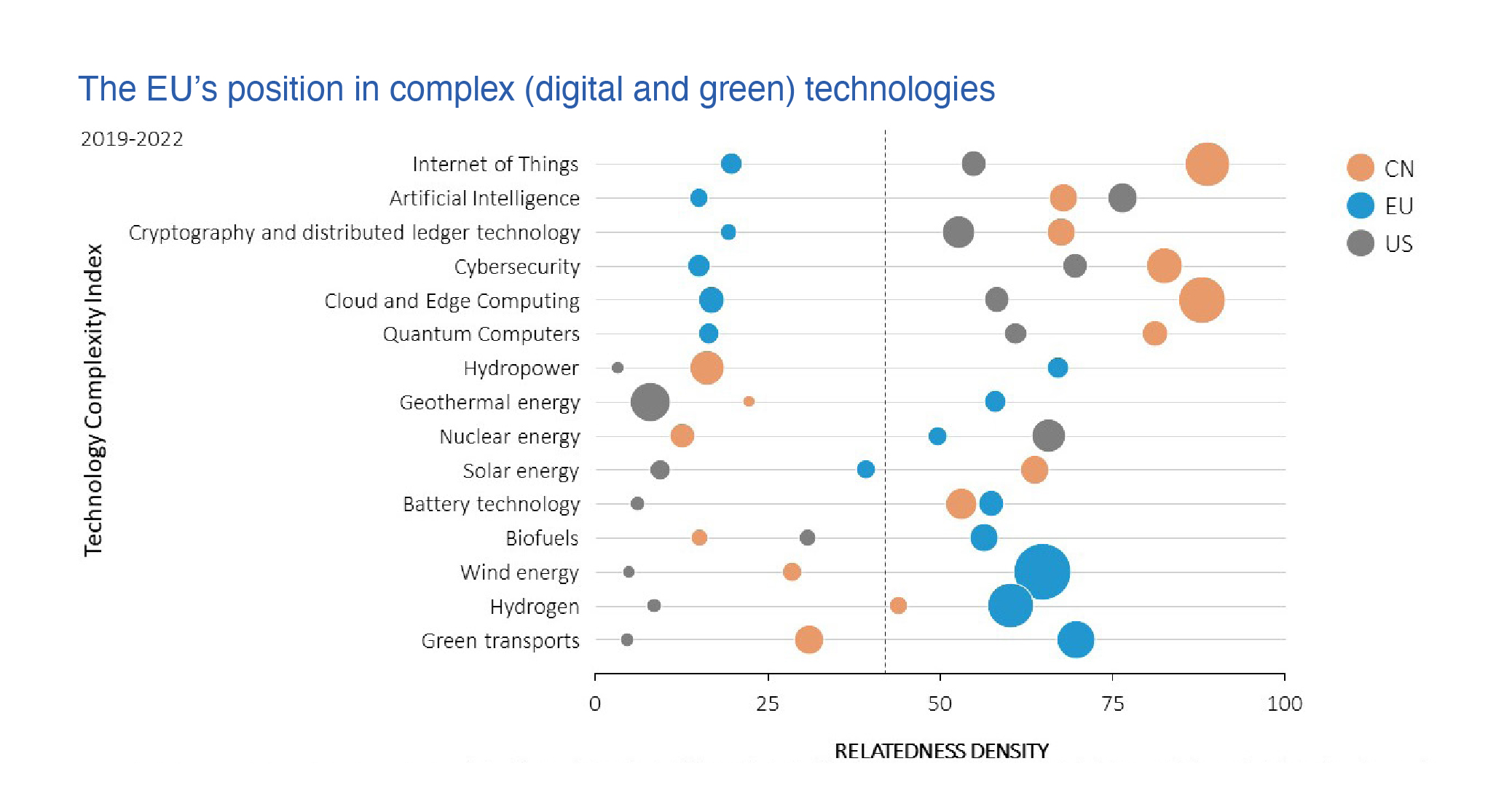

Draghi notes that 70% of the world’s wealth in the next 10 years will be digitally enabled. But Draghi observes that “[t]he EU suffers from limited capacity to benefit from ‘winner takes most’ dynamics, network effects and economies of scale in key technologies - except for next generation materials and clean technologies”, illustrated in the following graph which maps across a range of digital and green technologies the US, China and EU’s technology sophistication by their abilities to deploy and build a competitive advantage in each technology:

Most EU innovation activities are primarily concentrated in sectors with medium-to-low R&D intensity, risking the EU being stuck in a ‘middle technology trap’:

Among leading companies in software and internet globally, EU firms represent only 7% of R&D expenditure, compared with 71% for the US and 15% for China. Furthermore, “[o]nly four of the world’s top 50 tech companies are European” .

In 2023 car companies were the biggest R&D investors in both the US (Ford) and the EU (Mercedes-Benz). Today, software companies are the biggest R&D investors in the US (Alphabet, Meta, and Microsoft), while car companies continue to be the biggest in the EU (VW, Bosch, and Mercedes-Benz).

Even in green technologies, the EU is squandering its early lead to China: from 2015 to 2019 the EU represented 65% of global early-stage VC for hydrogen and fuel cells, this share declined to 10% from 2020 to 2022.

Telco

Draghi makes the obvious point that ubiquitous highspeed fixed, wireless, and satellite networks are fundamental to improved EU digital competitiveness. As deploying AI will require faster, lower latency and more secure connections. Draghi says “[the declining profitability of the telecom sector now may represent a risk for industrial companies in Europe, in a phase when state of the art infrastructure is required to digitise manufacturing, supply and distribution chains”. In Europe, both revenues per subscriber and capital expenditure per capita are less than half the US’ and Japan’s level.

Telcos, particularly mobile operators, face the challenge of serial network investment as each new generation of technology comes along, such as 5G which Draghi estimates will cost EUR 200billion to deploy across the EU. He also identifies other factors draining the economic sustainability of telcos:

While the online digitalisation of much of the economy creates new business opportunities for telcos, going up the value chain also requires substantial investment, on top of spectrum and network costs: “[r]evenue-generating innovative services (IoT, edge computing, API commercialisation) require relevant upfront investment by Telecom operators, who are today constrained and with limited financial flexibility to commit further capital to innovative platforms”.

Telcos face stiff competition from over-the-top providers: “[a]s network services are being progressively managed by software, as opposed to by dedicated telecom equipment, offers of standalone communication applications independent from networks are leading to further disintermediation of telecom operators and threatening the business of traditional equipment providers, historically based in Europe”.

Draghi lays the blame at the door of overly cautious competition authorities and greedy governments:

“In the EU, ‘ex ante’ regulation - e.g. to prevent undesirable price effects - and EU and national competition policies have all favoured a plurality of players and low consumer prices”. Rejection of full mergers and infrastructure deals between operators disincentivised consolidation, favouring a multiplicity of smaller players in each market compounded by misguided ‘market-maker’ interventions by regulators (e.g. regulated access for MVNOs): [“[n]ew and non-investment-based operators have been supported and remedies imposed upon attempts to consolidate the market into larger players [which] has led to the creation of additional smaller players, reducing or eliminating the benefits of consolidation”. The EU has a total of 34 mobile network operators (MNOs) and 351 non-investment-based virtual operators (MVNOs), compared with 3 MNOs in the US (plus 70 MVNOs) and 4 MNOs in China (plus 16 MVNOs).

“Spectrum policies have been uncoordinated across Member States and mostly designed to maximise frequencies’ pricing and limit frequency bands and their life for existing players”. The limited term of spectrum licences serves no real purpose beyond providing an opportunity for governments to cash-in again on renewal, straining the sustainability of mobile operators as they face the massive upfront costs of investing in new technology like 5G and 6G to use that renewed spectrum. Spectrum caps and reservations also impair scale benefits for holding larger spectrum bands necessary to improve speed, quality, and ubiquity. Draghi notes the US, instead, permanent spectrum ownership and unconstrained auctions allow the possibility for telecom operators to use or freely sell portions of the spectrum.

Draghi’s telco recommendations include:

Double (at least) the term of spectrum licences.

Reduce country-level ex ante regulation favour rather ex post competition enforcement in cases of abuse of dominant position or other anticompetitive conducts.

Introduce a ‘same rules for same services’ principle to remove regulatory arbitrage across providers from adjacent sub-sectors providing similar services: for example, ensure network-based services and OTT services are regulated equivalently.

Encourage commercial contractual agreements (backed by mandatory arbitration) for terminating data traffic and infrastructure cost-sharing between internet service providers or telecom operators owning the infrastructure and very large online platforms (VLOPs) using it.

Incentivise the deployment of new infrastructures by defining cut-off dates for older technologies to enhance the return profiles of investments in new technologies - with measures to protect the most vulnerable customers.

Ensure enough spectrum for 5G and 6G by finding an additional spectrum for private Wi-Fi.

AI

Draghi paints an even bleaker picture of AI on both the demand and supply sides:

Currently, AI is adopted by only 11% of EU companies (vis--vis a 2030 target of 75%), and 73% of foundational models developed since 2017 are from the US and 15% from China. The risk is for Europe is to be totally dependent on AI models designed and developed abroad for both general-purpose AI and, progressively, for vertical uses dedicated to crucial EU sectors, including the automotive, banking, telecoms, health, mobility and retail industries Taking the top global AI start-ups worldwide, 61% of global funding goes to US companies, 17% to Chinese companies, and only 6% to those in the EU.

There are some bright spots:

Almost half of the over 1,000 service robots suppliers worldwide are European, although somewhat ironically, 73% of all newly deployed robots are installed in Asia and only 15% in Europe.

Big EC-funded tech projects are world leading. The Euro-HPC Joint Undertaking has created a large public infrastructure for computing capacity located across six Member States, which is one-of-a-kind globally. Three EU supercomputers (Lumi in Finland, Leonardo in Italy and Mare Nostrum 5 in Spain) are in the top ten worldwide. The challenge is now to open that computing power to private innovators.

Draghi says the main reason the EU is caught in “a vicious circle of low investment and low innovation” is a relatively underdeveloped financial ecosystem. The limited development of angel investors, venture capital and growth finance is an important driver of this financial gap for innovative start-ups in the EU compared. The share of global VC funds raised in the EU is only 5%, compared to 52% in the US, 40% in China, and 3% in the UK.

However, Draghi also thinks “[r]egulatory barriers to scaling up are particularly onerous in the tech sector, especially for young companies”. In part, this is a consequence of the ex-ante approach taken to regulation, such as with the new AI Act: “many EU laws take a precautionary approach, dictating specific business practices ex ante to avert potential risks ex post”. This is then compounded by EU competition enforcement policy, which “possibly inhibits intra-industry cooperation”, such as on pooling data for AI training and development of open or common standards.

He says that, while well-intended to protect consumers and citizens, “[t]he net effect of this burden of regulation is that only larger companies - which are often non-EU based - have the financial capacity and incentive to bear the costs of complying. Young innovative tech companies may choose not to operate in the EU at all”. The risk is that European companies will be excluded from early AI innovations because of uncertainty of regulatory frameworks as well as higher burdens for EU researchers and innovators to develop homegrown AI.

Draghi also cautions against regulation continuing to pile up as politicians and regulators respond to understandable but misplaced public concerns over AI:

AI is already a source of anxiety for European workers: almost 70% of respondents in a recent survey favoured government restrictions on AI to protect jobs. The impact of AI in Europe has so far been labour-enhancing rather than labour-replacing: there is a positive association between AI exposure and the sector-occupation employment share.

Draghi recognises that some digital services are already ‘lost’ to the EU, including cloud, and instead he recommends an ‘EU Vertical AI Priorities Plan’, focused on domain-specific innovation, such as in health and environment, backed by co-ordinated State aid. He says that to succeed (emphasis added):

This effort would be fed with data freely contributed by EU companies and supported within open-source frameworks in data-intensive industries, duly safeguarded from EU anti-trust enforcement, to encourage systematic cooperation between leading EU companies for generative AI and EU-wide industrial champions in key sectors.

This brings us to the firecracker in the Draghi report - his recommendations for revamping of EU competition law.

2. New Industrial Policy and the role of competition law

Draghi disavows recommending a revolution in competition law, and instead quotes Nobel Laureate Jean Tirole (2022):

what is needed is not a drastic change in antitrust law; indeed, the age-old statutes are worded in a broad enough manner that many of the behaviours we are concerned about are somehow already embodied in law. In contrast, the regulatory apparatus must be made more agile and in tune with evolving economic thinking in the digital age.

Draghi observes that given the strong and growing need for scale and the trends towards de-globalisation, there is a pressing need to strengthen internal (domestic) markets to foster productivity. Draghi clearly has in mind a repointing of competition law towards promoting the New Industrial Policy he is advocating.

In his words, “competition policy should continue to adapt to changes in the economy so that it does not become a barrier to Europe’s goals”. The tension between competition policy and industrial policy has been with us for some time: competition for competitions sake vs government picking winners (for example, through the use of trade interventions).

Draghi argues “[a]lthough it might sound paradoxical, strengthening competition goes well beyond traditional competition policy” in a radically different world driven by ‘winner takes most’ dynamics, network effects and economies of scale in key technologies:

Evidence that industrial policies can be effective under certain circumstances is growing. But to avoid the pitfalls of the past - such as defending incumbent companies or picking winners - these policies must be organised according to a set of key principles which embed best practice. Among others, the focus of such policies should be on sectors rather than companies; public support should be continuously evaluated, underpinned by a rigorous monitoring exercise; and market failures should be clearly specified and public authorities should avoid duplicating what the private sector would already do. The interaction with competition authorities is also critical for success.

Draghi makes the following recommendations for reform of EU competition law:

Competition regulators are currently too focused on lower price as a measure of competitiveness, and they should give more weight to innovation and future competition:

Lower prices in Europe have undoubtedly benefitted citizens and businesses but, over time, they have also reduced the industry profitability and, as a consequence, investment levels in Europe, including EU companies’ innovation in new technologies beyond basic connectivity.The economy has shifted towards more innovation-heavy sectors where competition is usually based on digital technologies and brands, where both scale and innovation are critical to compete rather than just low prices.

In mergers, there should be a more explicit, clearly articulated ‘innovation defence’ justified by the need to pool resources to cover large fixed costs and achieve the scale needed to compete at the global level. To help temper regulators’ scepticism of claims of future innovation (and reduce risks of misuse by merging parties), regulators should be able to seek enforceable investment commitments.

The current practice of enforcing competition policy does not emphasise security and resilience, but these elements should get more weight in competition evaluations, since they have become increasingly important in today’s world.

There should be a New Competition Tool (NCT ) which enables the EC competition authority to carry out a market study in a sector to identify the competition problem and then a market investigation determine the solution together with firms to solve it (as in the UK). The NCT would be available where there is i) there is tacit collusion; ii) the need for consumer protection is more likely to be needed, for instance due to consumers belonging to sensitive categories or having behavioural biases; iii) economic resilience is weak, one cause of which could be market structure (e.g. reliance on a single source of raw material) leading to frequent shortages or other harmful outcomes; iv) the information/data received by the authority indicate that the commitments or remedies adopted are not delivering competition.

Competition regulators should have expanded powers to require firms to provide information and regular reporting so that markets developments can be tracked in a more accurate and timely fashion.

There should be a streamlined process for - and a more favourable attitude towards - horizontal cooperation agreements and concerted practices to achieve R&D investment, sustainability transitions, data pooling, infrastructure sharing and standards development

3. Conclusion

While the Draghi report is driven by the EU’s fear of falling behind the US and China, and many of its recommendations are specific to the challenges of the incompletely executed Single Market, it still should be though-provoking for policy makers and regulators beyond the EU.

It would be an oversimplification to characterise the Draghi report as calling for a rollback of traditional anti-trust approaches. Nor is it advocating to simply defend national champions that can stifle competition and innovation.

Rather, the Draghi report emphasises the need to abandon certain ideological entrenchments, such as focusing solely on backward price effects, and to focus more on forward looking enhancements to quality and innovation in digital sectors. This shift aims to create a more dynamic and coherent alignment between Europe’s societal goals and its industrial strategy, including competition and trade policies.

Read more: EU competitiveness: Looking ahead

Peter Waters

Consultant