If you met a time-traveller from 10 years in the future, and they told you that AI was now ubiquitous in your profession, how would you feel?

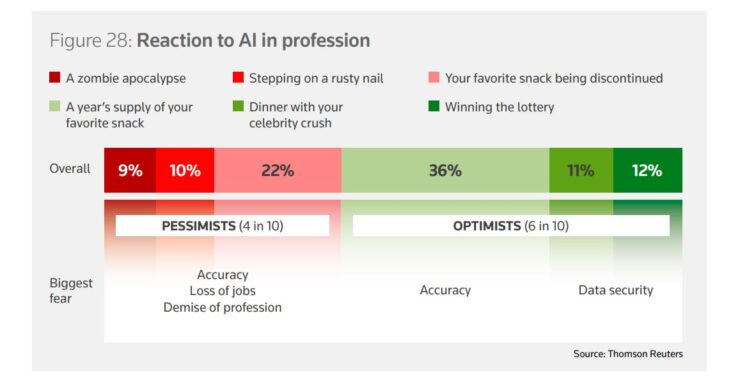

This was asked as a ‘playful’ question rounding out a global survey by Thomson Reuters of 1200 legal , tax, accounting, risk, and compliance professionals. The results ranged from, on one end, equating the outcome to a zombie apocalypse, to, on the other, winning the lottery. Where do you fall on this scale? And re-test yourself after reading this article.

Two weeks ago, we discussed one of the biggest ‘rusty nails’: a Stanford University study of the disturbingly high levels of hallucination by AI when dealing with legal issues.

This week we present key points from a panel, organised by Microsoft, between three leading Australian law and generative AI experts Clayton Noble (Microsoft), Patrick Gunning (King & Wood Mallesons), and Caryn Sandler (Gilbert + Tobin), who would firmly plant themselves on the ‘winning the lottery’ side.

What can AI do?

Apparently, a lot in law: Goldman Sachs predicted that 44% of legal work could be undertaken by AI, compared to 28% for healthcare and 6% in construction.

But joint research between Microsoft and the Tech Council of Australia shows the need to unpack this: while this research found 10% of solicitor tasks could be fully automated, 35% would involve AI and human lawyers working together to ‘enhance’ the legal task and the output.

The three panellists, Noble, Sandler and Gunning explored what many see as the biggest advantage to engaging with generative AI in legal practice: the scope for lawyers to prioritise and redirect their focus to what the panel described as ‘higher skills’. Allowing lawyers to relieve themselves of repetitive tasks and free themselves up for strategic work, distinct from those tasks that do not require human judgment. The panellists referred to key examples around summarisation and simplifying complex drafting, creating more user-friendly documents, and research. Additionally, generative AI may be able to improve processes around non-billable administrative tasks. AI’s strength is in its ability to recognise patterns and implement templates.

As Microsoft has sought to highlight in the very name of its LLM Chatbot:

Generative AI has the potential to serve as a ‘copilot’ - augmenting but not replacing lawyers in completing routine, repetitive and time-consuming tasks. Yet crucially, generative AI systems and tools are only as good as the material they’ve been trained on, as well as their probability-based approaches. As such, legal practitioners must maintain a human in the loop to review, edit, customise and quality-assure content.

AI in the "Value Chain"

There are two contrasting positions on the impact which generative AI could have on the legal profession:

on one view, the legal profession is built on a foundation of repetitive work or linear thinking. Therefore legal work is low-hanging fruit for artificial intelligence, as it is fundamentally a form of “advanced pattern recognition”, as said by contributors to the UK Law Society’s “Images of the Future World Facing the Legal Profession” project. This perspective would leave lawyers more vulnerable to substitution than other professions.

on the other view, law can be seen as requiring non-linear thinking. By contrast, generative AI is built on mathematical probabilities and ascertains its responses by predicting the most likely next word. AI is therefore essentially a linear tool. Meta’s chief AI scientist Yann LeCun noted that, in his view, AI in fact has “less common sense than a house cat” . Another UK Law Society contributor described this way of thinking as not having a “yes/no” answer. This perspective may mean AI may not be as helpful to the legal profession if lawyers rely on non-linear thinking.

At the risk of sounding too lawyer-like, the reality is likely somewhere in between. You will be hard-pressed to find a lawyer that has escaped the less-than-riveting (albeit important) preparatory tasks in a due diligence or a discovery matter. Yet the reason many of us stick around is that linear work then feeds into out-of-the-box, template-less solutions that are as curved as thinking can get.

This reality - of legal work requiring both linear and non-linear thinking - is reflected in the panellists’ analogy for the AI-lawyer relationship. They likened it to that of the junior lawyer (often involved in linear thinking) and their partner (often involved in non-linear thinking) wherein “the same way that you would review an advice that is done by a junior today, you would have to review any output that comes out of generative AI ”.

This is also because of the important supervisory role lawyers must play with AI. This is built into legal professional rules and the fundamental obligation to act with due care and skill. To allow AI to replace work without maintaining oversight and review would be to neglect that duty entirely. For both the non-linear additions, and the duty of care, the legal profession will need human intervention, regardless of the efficiency and effectiveness of generative AI as a complementary tool. The panellists noted that

the professional obligations remain the sameyour application is slightly different because you are leveraging it off the back of technology, rather than actual human content.

Finally, there are some who would argue that even though this linear/non-linear distinction in legal work represents a current boundary line for AI in the law, AI will soon blow past it. The UK Law Society’s future report quotes writer Adam Greenfield:

AI as we understand it - and are currently developing it - is actually best at precisely those things which are the higher creative or strategic functions. I think there’s a very dangerous tendency for people who are currently very well compensated for having executive, creative or intuitive seeming tasks in the world [to think that their jobs are safe]; I think those are some of the things that’ll get automated first. here are some who argue that, not so far down the track, AI will blow past this linear/non-linear distinction in legal practice.

Issues

Confidentiality and Client Privilege

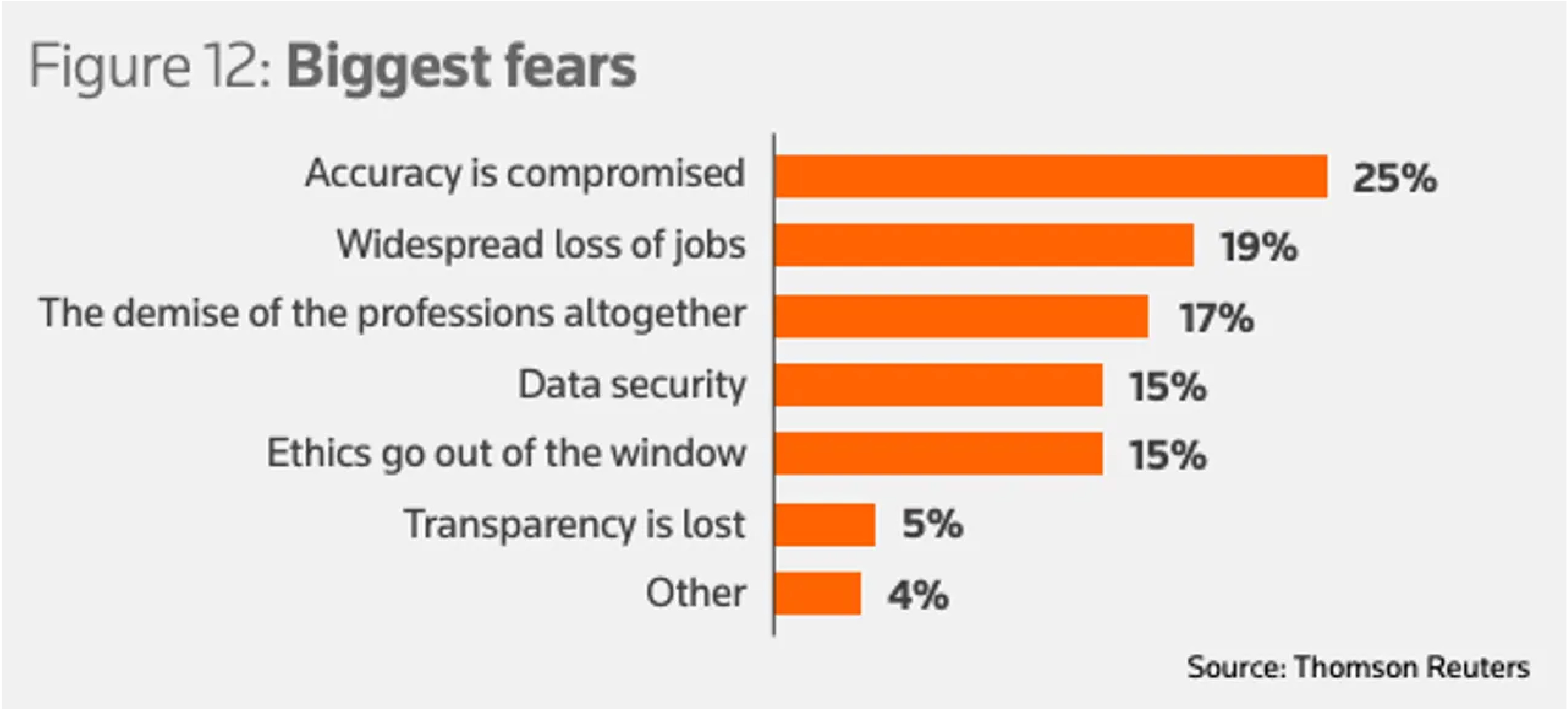

It will not be news to readers that data security and confidentiality is a concern of lawyers using AI. So it is almost surprising that the Thomson Reuters study found only 15% of professionals cite data security as their greatest fear in relation to the adoption of generative AI in practice.But while legal professionals may be ‘worrying about their own skin’, our three panellists acknowledged that clients were very much focused on their data, noting that “in standard retainer agreementsmany have added a new clause this year saying, ‘don’t use our data to train AI models”. This could present challenges to law firms seeking to fine tune foundational models with higher quality data more specific to their practices and clients.

But what other issues are out there?

The era of the AI super user

One of the critical concerns surrounding the explosive development of generative AI is that generative AI will replace particular jobs, ranking as the second highest concern amongst participants in the Thomson Reuters study. Again, your view on this depends on the extent to which you believe legal practice involves more than mere pattern recognition. As outlined in The Law Society’s ‘Images of the Future Worlds Facing the Legal Profession 2020-2030’ paper, “trust [is]a key factor in promoting lawyers’ knowledge and relevance, as well as the judgment and reasoning they can bring to complex situations ”. If journalism is an analogy, a recent survey by the London School of Economics finds that while use of AI is widespread in media companies globally, the survey found no signs of job losses and that respondents were more focused on the need to create new jobs to provide technical support for AI in the newsroom.

Case Study #1: AI as a Co-Pilot - Journalism

AI as a co-piloting tool is already prominent in the journalism industry. Whilst there have historically been great fears around the ability of AI to replace journalistic integrity, journalists are now experimenting with, and utilising generative AI to co-pilot their writing. Generative AI is enabling more in-depth investigative reporting and enabling fact-checking on the spot.

However, there is still a word of warning: while artificial intelligence is unlikely to entirely replace legal professionals, it is certainly true that professionals who are trained in, and engaged with generative AI, will replace those who aren’t. Willingness to learn and adopt the new technology will be critical in the legal industry moving forward.

The panellists discussed this topic in relation to the rise of “fast adopters ” and “super users ” as being critical to the emerging state of legal practice. It will be useful to “leverage [these super users’] enthusiasmfor the benefit of everybody ”. Particularly for young and new practitioners, who are seemingly more invested in, and motivated by, the ways in which they are doing legal work, adoption of this technology will mean significant improvements in process and efficiency, along with the inevitable shift in skillset and digital literacy requirements.

Knowledge management

A further use for generative AI is based in its knowledge management and knowledge-transfer capabilities. Law firms invest significant time, money and effort into drafting and preparing precedents, and training their lawyers to adopt and operate within the parameters of those precedents, to standardise the quality of work exported from the firm. The scope for standardisation and knowledge transfer, when utilising generative AI as a copilot, is immense.

Case Study #2: AI as a Knowledge Transfer Machine - Customer Service

In call-centres, this type of knowledge transfer has already been experimented with. AI operating as a co-pilot to technical advisors offering customer support, where the AI learns from the answers of good customer support staff and redistributes these answers to assist bad or inexperienced staff. The impact of these tools has been to increase productivity, cut training times, and improve retention.

However, it is essential that we critically engage with the risks of this particular AI function. With knowledge transfer comes a greater risk of homogenisation between law firms, particularly given challenges around intellectual property and AI.

Keeping up to date:

The law is constantly changing, through case law, legislation and most dynamically of all, delegated rule making by administrative agencies. But AI is trained on a fix, historic corpus of training data, which means that its knowledge is ‘frozen in time’. In fact, trying to keep AI up to date by adding in new information can result in ‘catastrophic forgetting’, when the model forgets previously learned information as it learns new information (the new ‘overwrites’ the old).

The panellists discussed the benefits of a new AI technique called retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). This involves retrieving facts from an external knowledge base outside the LLM, which can be readily updated, and then used to ground LLMs on the most accurate, up-to-date information, giving users insight into LLMs' generative process. The RAG process enriches the original prompt: algorithms search for and retrieve information relevant to the user’s prompt by ‘looking’ in the external database(s), and then update the user’s prompt with that external knowledge which is passed to the language model. The external RAG database can be open source or more usually for law firms, a closed domain database, such as a law firm’s internal KM database.

Rewarding human lawyers

An additional obstacle arises when relying on generative AI for the transfer of knowledge between legal professionals: if AI learns from high performers and transfers that knowledge to others, how do you identify, recognise, and reward those high performers? It may become increasingly harder, as output becomes progressively homogenised, to engage employees through merit-based rewards. The more reliance is placed on generative AI to improve performance, the more workplaces will have to reform the way they recognise and reward their workers.

Relatedly, generative AI systems will have to be trained to learn and disseminate the work of effective lawyers and avoid adopting practices of ineffective or “bad” practitioners, with organisations needing to also focus on adopting appropriate governance protocols. Generative AI may operate as a tool to further the movement of knowledge from good, effective lawyers to inexperienced or junior lawyers. If taught to standardise towards best practice legal work, generative AI may also provide a guardrail against “bad” or ineffective lawyers.

Overall: as work becomes standardised through the use of AI, it must be standardised to the betterment of the whole practice and its clients, not to their detriment.

Do external and in-house lawyers feel the same about the opportunities of AI?

The panellists all acknowledged that, despite clients not wanting to be the guinea pigs (as noted with their generative AI clauses above) businesses nevertheless have great enthusiasm for generative AI’s potential gain for in-house counsel. That enthusiasm was focused on AI undertaking those linear tasks of repetitive and mundane work, freeing up counsel to engage in higher-level work.

But private practitioners and in-house counsel also have different focuses in the use of generative AI, as highlighted by the Thomson Reuters study:

for law firms, the focus was on productivity impacts, enabling faster and more efficient processes, knowledge sharing and output.

in-house lawyers were more enticed by the prospect of a tool to facilitate efficient tracking of regulation and legislation. This finding was also reflected in the panel discussion, with Sandler acknowledging that “the regulatory environment in which we operate, the complexity in the broader environment, [means there] isfar more work going in on a daily basis into in-house legal teams[gen-AI] is a really great opportunity tofree them up to deliver on that legal work ”

Conclusion

The potential impacts of generative AI in the legal industry will be vast, and the responsibility on legal and other professionals to engage with its limitations and complexities is imminent. Regardless of where you land on the spectrum from lottery-winner to zombie apocalypse, generative AI is developing, and will continue to develop, at a significant pace. It is now time to engage with it closely and consider how it will fit in to your work. Having read our article, are you convinced of the use case for generative AI in law yet?

Listen to more: Can generative AI safely, securely and responsibly help your legal work? .

Peter Waters

Consultant