Oxford University’s Internet Institute has recently published a landmark (and visually striking) report on the scope of human/AI creative complementarity based on interviews with some of the world’s leading AI artists.

The report’s cover itself as the product of AI/human collaboration:

The image on the left was produced by prompting an AI-backed online text-to-image generator (WOMBO Dream) with the title of the report (“AI and the Arts: How machine learning is changing artistic work”). The image on the right is the report’s cover produced by a human artist, Alexandra Francis, using the generated image.

Speaking of the ‘collaboration’, Alex was clear that she was the artist and the AI was only a prompt:

‘Sometimes, starting a piece of work, you’ve got an idea in your head, but later realise that you’re rehashing something you’ve seen. You think, oh no, I’m ripping someone off, I’ve seen too many things on the internet and I’m taking somebody else’s idea. But a generated image is completely unique. It’s a nice way to make something original.’

How is AI art different from computer art of the 70s?

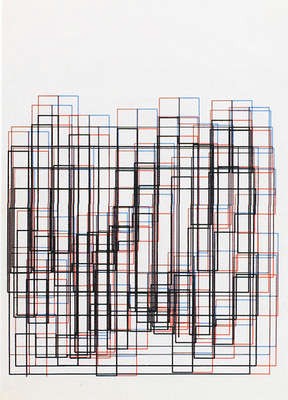

In the 1960s and 1970s, the pioneers of computer art (Frieder Nake, Vera Molnar, and Manfred Mohr, among others) ‘explicitly harnessed early computers to pitch chance against control in order to produce unexpected results’––what Friede Nake described as drawing “with eyes wide shut”. Essentially, the computer would be programmed with a macro-aesthetic model (e.g. draw polygons), some micro-aesthetic (colours, shading etc), mediate these with random numbers, and then visualise the computed numerical results by allocating the shading and colours to the numbers. Nake’s computer-generated art looked like this:

The difference with modern AI models lies with their ability to learn. As one artist contributing to the Oxford report said:

‘With old computer art, the key difference lies in rules. ML art is a bit more exciting, because in traditional computer art, a programmer is feeding the machine rules through programming. If you wanted to make a generated landscape in the '70s, you would have to program it into the computer, draw ground on the bottom, draw trees in the middle, and draw sky on the top of the painting. You would have to hard-code rules into the computer, and the computer would execute those perfectly. But with neural networks, what happens is you're still feeding rules to the machine, but it happens through the dataset. You choose a dataset that conveys the rules that you want to get across, then you allow the machine to try and pick up those rules.’

But not AI as you and I know it

The Oxford report found how artists are using AI goes ‘against the grain’ of how AI is used in the commercial world. AI’s ability to process massive amounts of data means it can generate perfect images which are indistinguishable from the real world – ‘deep fakes’ - whether photographic images of non-existent humans or a ‘new’ Van Gough painting. Most AI artists were turned off by this capability of perfect image generation because ‘lot of people ask me whether the images are done using Photoshop’.

Instead, the artists interviewed for the Oxford report were unanimous in their view that the most interesting dimensions of practising with AI models relate to mislearning. Robbie Barret has created a series of nudes from misinterpreted images generated by AI:

‘The misinterpretation part, I think, is the most exciting part, because you can get really surprising outputs, that you, as the artist, were not expecting. You could do that with traditional computer art, but it would be because you made an error within your parenthesis, or you messed up the logic on a line, so you get some glitchy output. The glitches or misunderstandings that happen with neural network art are a lot more meaningful. …. With my nude portraits, the network totally misunderstood the high-level organization of a nude portrait. It’s a semantic glitch’.

The artists induced their AI to mislearn in two ways. First, while AI models function best with large amounts of data, these artists instead feed their AI with more ‘human scale’ amounts of data: which artist called “Little AI”. Second, they also ensured the AI does not learn too much. One artist said:

‘I watched the GAN learn, and I chose when to cut it off from learning. That sounds a bit arbitrary, but how long it learns really does affect the output. After the networks had already learned how to make landscape things well, I noticed that every few days of training it would alternate between making really bright, psychedelic landscape paintings, and really dark, moody ones. So I cut it off when it was making the darker paintings because I enjoyed those more.’

What’s the artistic output?

Computer art of the 70’s conformed to the model of producing static, single images as the art work that could be hung on the wall. However, as the Oxford report points out, because generative models are probabilistic in nature, the outputs artists generate are not single images, but classes of images. Some artists go so far as to argue that the true artwork is, in fact, the algorithm itself.

The next step is finding ways to exhibit the entire class of works in non-static installation. In 2019, Sotheby’s auctioned the work of the leading AI artist Mario Klingemann titled ‘Memories of Passers-by’ which consisted of multiple GANs, two 4k screens, custom handmade chestnut wood console, which hosts AI brain and additional hardware (see image below).

But AI artists still confront viewers’ preferences for ‘a hang it on the wall’ image. One of the artists interviewed for the Oxford report said:

‘I recently did this private event where I had a big screen projecting my images non-stop, and also a small exhibit with a dozen images. My images are usually small, A4 or A3. People still spent all their time looking at the prints, studying them. Hardly anybody looked at the screen. I mean, you sit at a screen the entire day. People aren’t interested.’

Is AI an artistic tool or a co-creator?

The Oxford report concludes that creativity was at the heart of being human, and AI can’t do that:

‘While ML models could help produce surprising variations of existing images, practitioners felt that the artist remained irreplaceable in giving these images artistic context and intention––i.e., in making artworks. They highlighted that the creativity involved in artmaking is about making creative choices, a practice outside of the capabilities of current ML technology.’

As one artist put it ‘you wouldn’t say that a piano is making the art. It’s just a tool.’

A more nuanced view which acknowledged that the capacity of AI to surprise the human artist put it this way:

‘..though [AI] models have the ability to generate surprising outputs, they entirely lack the capacity to anchor these outputs in the world. Unlike the kind of creativity valued in humans both in and beyond the arts, ML has little scope for contextualisation. When I view creating an artwork, there needs to be soul in an artwork. This is different than design or other things. Artworks have to touch your soul, touch you emotionally as well as visually and intellectually. For that, AI runs into trouble.’

The Oxford report identified a ‘sci-fi’ view of AI amongst the general public as leading to an overestimation of AI’s ability to be creative. Artists considered mystification and anthropomorphising language around AI to be irresponsible:

‘There are conflicts and contradictions in this as well. One part of me wants to say, “Look at this crazy thing, it’s making us think about our own consciousness. It’s doing this incredible creative thing.” And explain it to people that way. But I’ve realized that’s irresponsible. The more I learned about it, the more I noticed artists who are more in the public eye, who don’t fully understand the technology, writing curatorial statements and texts saying, ‘this is artificial consciousness’, and mystifying it on purpose for the art audience.’

Even so, there seems to be some doubt or disquiet in corners of the Oxford report. Picking up the piano example, one artist noted that ‘the great thing about [AI-generated] piano phrases is that a lot of them can’t be played by human hands. It’s helping me create something that no human would actually be able to play.’ Is this a case of AI writing music for itself?

The Oxford report also says that working with AI models, ‘involves balancing heightening surprise with the frustration of having less control over one’s medium.’ As one artist explained:

‘A lot of my work is about misinterpretation, and that can be a double-edged sword. It’s cool when the network misinterprets things and gives you surprising results, but it’s also very frustrating when you cannot get the exact image that you want. I feel like I have a lot less control over the exact thing that I’m making. It’s not like I’m a painter where I can just place a brushstroke wherever I please. I’m working with a larger system. If I had to describe working with algorithms, I’d have to say it’s a split between frustration and nice surprise all the time.’

If the human artist has ceded a degree of control, does that mean the AI has a degree of artistic agency?

Could AI developers have a career as AI artists?

Frieder Nake, the 70’s computer artist, was a mathematician and computer scientist. However, the Oxford report argues that while the boundaries are porous, the AI Art field does tend to differentiate itself from those who are highly technically orientated but who have little knowledge or understanding of the art world. As one artist:

‘I don’t want to put down engineers working in art at all––there are people who succeed doing that––but some people don’t necessarily come at it from quite the right angle. I see lots of parallels with the early days of photography, when many photographers were trying to validate this new medium by mimicking paintings. These were the engineers, the people creating the chemical development processes, and they would take photos of Renaissance paintings and say, “this is a valid art form”.’

What is the future of AI art?

Landscaping painting by humans is not about to be overtaken by bucolic images generated by AI:

‘Uptake of machine learning tools in the arts do not, in themselves, unlock a step-change in human creativity, but instead build upon century-long trends in automation. Indeed, what we find is the progressive inclusion of the affordances of ML in the toolkit available to fine and media artists, accompanied by local changes in their creative process. Photography hailed the end of painting, video the end of photography, interactive NetArt the end of static artworks, and so on.’

Some of the interviewed artists thought that AI art would always occupy a marginal position in relation to the fine art because of the lack of “the physical index” (i.e. something to hang on the wall). Other artists believed that as the technical barrier to entry continue to fall, AI art may go mainstream, ‘but you need people who are in the art world to be adopting it for it to change. If Damien Hirst starts making AI butterflies, that becomes part of the tool set.’

Intellectual property rights in AI created works

An issue not addressed in the Oxford report is intellectual property rights on AI generated works.

Artists typically obtain protection for their work through copyright. However, in many countries (including Australia), in order for copyright to subsist in a work, it must be the product of independent human intellectual effort. AI generated works do not sit neatly within this framework and as a result they are generally not afforded copyright protection in Australia. However, there is scope for debate about how the human authorship requirement would apply to a work that is partially created by humans, and partially by an AI system (such as the AI/human collaboration on the report’s cover).

In some jurisdictions (such as the UK and New Zealand), the gap in protection for all computer generated works, including but not limited to AI artwork, has been dealt with through statutory reform. For example, in the UK the author of a “computer-generated” work is taken to be the person who undertakes the arrangements necessary for creation of the work (s 9(3) Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988).

It has become increasingly clear that the Australian position on human authorship may need to be reconsidered, in order to address existing uncertainties, and to provide the appropriate incentives and rewards to creators of AI technologies. As to the timing of this, Dilan Thampapillai makes the following useful observation:

‘What is missing here is the threshold event that would give rise to a paradigm shift in our thinking about AI. That is, a technological development has yet to occur that would represent a tipping point wherein AI moves from being a mere tool to being something akin to the master, thereby comprehensively replacing a substantial tranche of human labour. In the absence of such an event or development, the argument for extending copyright protection to works of nonhuman authorship is somewhat speculative’

Given the pace of change in AI technologies, it may be that such a threshold event emerges sooner rather than later.

Read more: AI and the Arts: How Machine Learning is Changing Creative Work

Visit Smart Counsel