The new Australian hybrid mismatch rules generally commence on 1 January 2019 with no grandfathering of existing arrangements (the imported mismatch rule discussed below applies to income years starting on or after 1 January 2020). Australia now joins the United Kingdom and New Zealand as jurisdictions that have enacted anti-hybrid legislation, and the European Union member states have committed to apply anti-hybrid legislation by 1 January 2020.

Taxpayers should be carefully reviewing all of their arrangements to consider the application of the hybrid mismatch rules and restructuring accordingly.

Key messages

The key messages for taxpayers in relation to the hybrid mismatch rules are:

- They apply to payments between unrelated parties as well as related parties.

- They catch a broad range of payments such as interest, royalties, rents and payments for services.

- They are more far-reaching than what they may initially appear to be and there is no de minimus threshold for their application.

- You will need to understand:

- Current foreign income tax laws and you will also need to monitor future developments in those laws; and

- The global structure of your group.

- You may pay tax because someone else (likely to be in a foreign jurisdiction) does not!

- You may need to revise valuations and cost of funding, and you may need to make announcements to the Australian Securities Exchange.

What is a hybrid mismatch?

Broadly, a hybrid mismatch arises where entities exploit differences (i.e. “hybridity”) in the tax treatment of an entity or instrument under the laws of at least two tax jurisdictions to defer or reduce the collective cost of income tax. Most commonly, this will be in the form of:

- A deduction in one jurisdiction for a payment, which is not assessed as income in the recipient jurisdiction (a deduction / non-inclusion (D / NI) mismatch); or

- A deduction in two jurisdictions for the same payment (a deduction / deduction (D / D) mismatch), which are sometimes colloquially referred to as “double dips”.

What do the hybrid mismatch rules do?

The rules neutralise hybrid mismatch arrangements for Australian taxpayers by either denying tax deductions or including additional amounts in the taxpayer’s assessable income.

When do the hybrid mismatch rules apply?

Generally, the hybrid mismatch rules will only apply to a taxpayer if it has entered into:

- A structured arrangement – a structured arrangement is an arrangement where the hybrid mismatch has been priced into the terms of the scheme or it is a design feature of the scheme (regardless of the relationship between the parties); or

- Certain arrangements with entities that are “related” or arrangements with members of the same “control group” – entities are related if one owns 25% or more in the other entity or they share a common owner with a 25% or more interest (on an associate inclusive basis). Entities are in the same control group if they are consolidated for accounting purposes, own 50% or more of the other entity or have a common owner with a 50% or more interest.

If the taxpayer has entered into one of the above arrangements, then the taxpayer needs to consider if the arrangement is one of 6 types of hybrid mismatch in order of priority as outlined in the table below. Please note that the hybrid mismatch legislation can be extremely complex and the table below provides a high level summary only.

| Hybrid mismatch | Type of hybrid mismatch | Description of the hybrid mismatch and examples | How the mismatch is neutralised |

| Hybrid financial instrument mismatch | D / NI |

Hybrid financial instrument mismatches exploit differences in the tax treatment of:

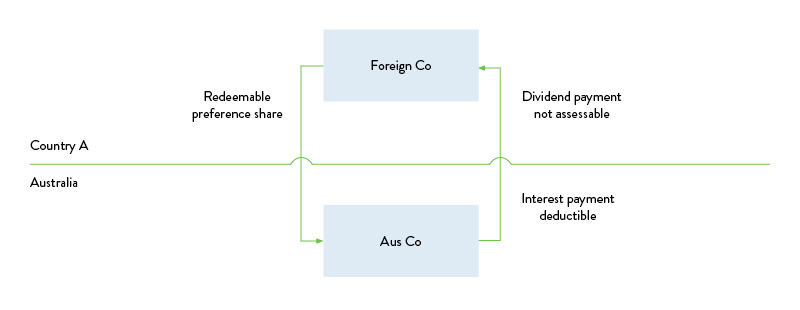

In the example below, a hybrid financial instrument mismatch arises as a consequence of Australia allowing a deduction for distributions paid on a redeemable preference share that is debt for Australian tax purposes, but Country A treats the distribution as non-assessable under a dividend participation exemption.

Another example of a hybrid financial instrument mismatch is a profit participating loan from an Australian taxpayer to a foreign entity which is treated as debt in the foreign entity’s jurisdiction (and interest payments are hence deductible), but the loan is treated as non-share equity under Division 974 and the interest payments are treated as non-assessable non-exempt income under Subdivision 768-A. It should be noted that there is an exception for hybrid financial instrument mismatches where the difference from the hybridity relates to a deferral of assessability of income for a period of 3 years or less. |

Depending on the circumstances, the mismatch is neutralised by either denying a deduction to the Australian taxpayer or including an amount in the Australian taxpayer’s assessable income. |

| Hybrid payer mismatch | D / NI |

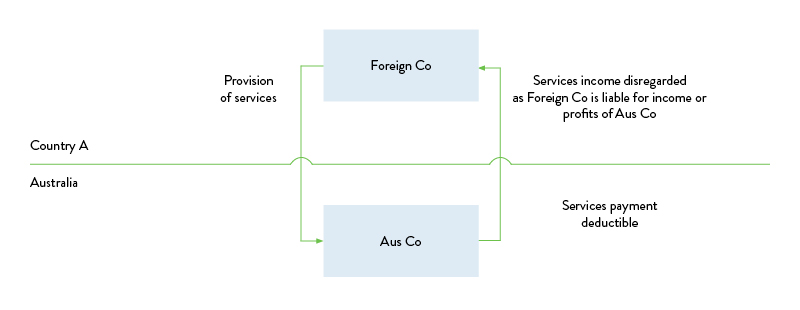

Hybrid payer mismatch arrangements exploit differences in the tax treatment of the payer. For example, consider a payment by an Australian subsidiary to its U.S. parent where a “check the box” election has been filed to treat the Australian subsidiary as a disregarded entity for U.S. tax purposes. A deduction would arise to the Australian subsidiary but an amount would not be included in the U.S. parent’s assessable income. Similar to the above, in the example below, a mismatch arises as the payment made by Aus Co (a “hybrid payer”) is deductible in Australia, but the payment is disregarded in Country A.

|

Depending on the circumstances, the mismatch is neutralised by denying a deduction to the Australian taxpayer, or including an amount in the Australian taxpayer’s assessable income. |

| Reverse hybrid mismatch | D / NI |

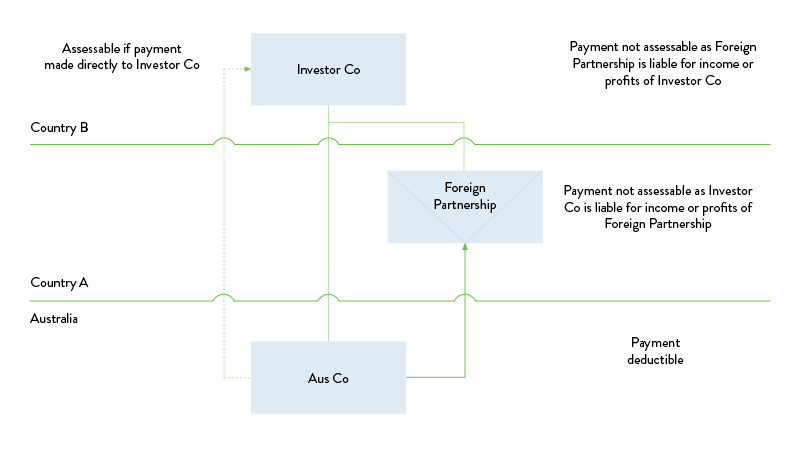

Reverse hybrid mismatches arise where a deductible payment is made from Australia and both the payment recipient’s jurisdiction and the jurisdiction of an investor in that recipient treat the payment as being allocated to the other jurisdiction, meaning that the payment received is not assessable in any jurisdiction. In the example below, Aus Co makes a deductible payment to Foreign Partnership, which is established in Country A. Country A regards Investor Co as the entity liable for Foreign Partnership’s profits on the basis that Foreign Partnership is a transparent or flow through entity. However, Country B regards Foreign Partnership as a liable entity and the payment made by Aus Co is not assessed in either Country A or Country B.

It should be noted that the reverse hybrid mismatch rules will only apply where the mismatch would not have arisen if the payment had been made directly to the investor. |

The mismatch is neutralised by denying a deduction to the Australian taxpayer. |

| Branch hybrid mismatch | D / NI |

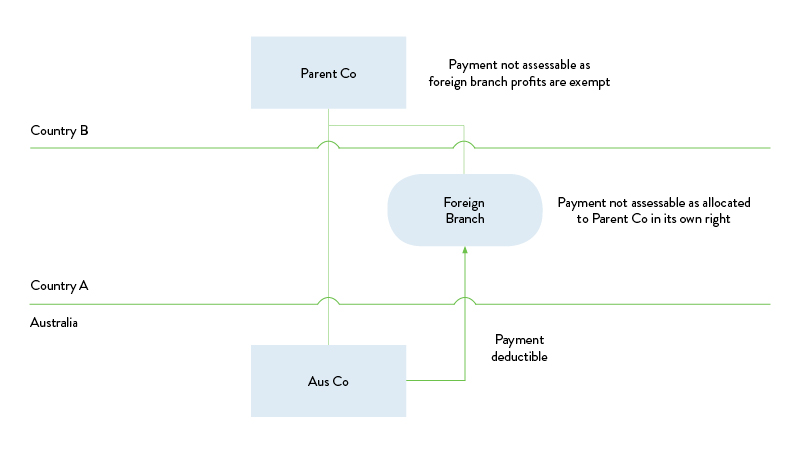

Branch hybrid mismatches arise where both the residence jurisdiction and the branch jurisdiction treat a payment as being allocated to the other jurisdiction, resulting in the payment not being assessed in any jurisdiction. In the example below, Aus Co makes a deductible payment to the foreign branch of Parent Co. Country B has an exemption for foreign branch profits. In Country A, the payment is regarded as having been paid directly to Parent Co, notwithstanding the existence of a branch. The payment by Aus Co is therefore not subject to tax in either Country A or Country B.

|

The mismatch is neutralised by denying a deduction to the Australian taxpayer. |

| Deducting hybrid mismatch | D / D |

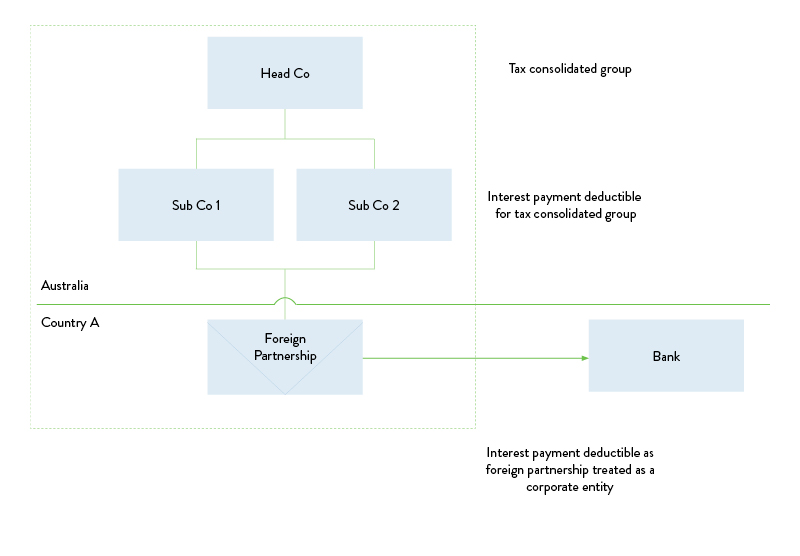

A deducting hybrid mismatch arises where two jurisdictions permit a deduction in relation to the same payment and the deduction is taken into account in calculating the taxpayer’s net income in both jurisdictions. In the example below, Sub Co 1 and Sub Co 2 are both members of the same tax consolidated group. They are also the only general partners in Foreign Partnership and Foreign Partnership is also a member of the tax consolidated group (noting that there is no residency requirement for a partnership to be a member of a tax consolidated group). Foreign Partnership is treated as a corporate entity in country A. The interest payment paid by Foreign Partnership to Bank is deductible in both Australia (to Head Co) and Country A (to Foreign Partnership).

|

The mismatch is neutralised by denying a deduction to the Australian taxpayer. |

| Imported hybrid mismatch | Integrity measure |

Imported hybrid mismatches arise when a hybrid mismatch is “imported” into Australia through an importing payment. Subdivision 832-H contains an integrity measure that applies when one or more entities are interposed between a hybrid mismatch and a country that has hybrid mismatch rules. For example, an Australian taxpayer makes a deductible payment which results in a hybrid mismatch outcome in a country which has not adopted OECD hybrid mismatch rules. |

The mismatch is neutralised by denying a deduction to the Australian taxpayer. |

Integrity measures, integrity measures…and more integrity measures

A further integrity measure in Subdivision 832-J

Further to Subdivision 832-H (imported hybrid mismatch), an integrity measure targeted at payments of interest (or payments of similar character) is included in Subdivision 832-J which is designed to prevent a multinational group entering into structures to circumvent the hybrid mismatch rules.

The measure targets arrangements where an equivalent D / NI mismatch arises through the use of interposed conduit entities in the same Division 832 control group which invest into Australia, and the principal purpose of the arrangement is to enable an Australian income tax deduction and foreign income tax to be imposed at a rate of 10% or less. If the integrity measure is enlivened, the Australian deduction will be disallowed unless the parent entity’s jurisdiction has an equal or lower tax rate and no hybrid mismatch would otherwise arise.

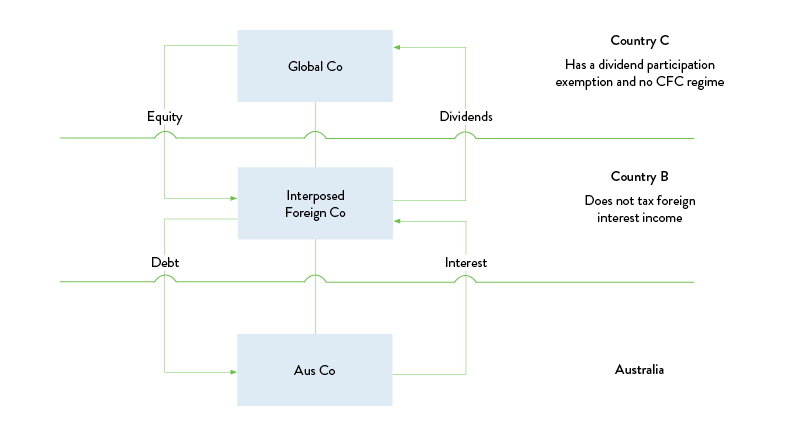

The example below illustrates the potential application of this integrity measure and highlights that multinational entities should consider its impact where intra-group financing exists through interposed foreign entities that gives rise to an Australian tax deduction and the imposition of foreign income tax on the interest receipt at a rate of 10% or less.

In the example, Global Co, Interposed Foreign Co and Aus Co are all members of the same Division 832 control group. Rather than Global Co lend money directly to Australia (in which case interest income would be assessed to tax at 20% in Country C), Global Co capitalises Interposed Foreign Co with equity which Interposed Foreign Co then lends to Aus Co. Interposed Foreign Co does not carry on a banking or similar business. Interest paid by Aus Co is deductible in Australia, but the interest payment is not assessed to tax under Country B’s tax laws. Country C does not have a controlled foreign company regime to attribute the interest income to Global Co and Country C has a dividend participation exemption such that dividends that Global Co receives from Interposed Foreign Co are exempt from tax. It is this type of arrangement that the integrity measure in Subdivision 832-J is aimed at, and whether it applies will depend on whether the arrangement was entered into for the principal purpose of enabling the D / NI outcome.

Restructuring hybrid arrangements and Part IVA

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO or Commissioner) acknowledges that the enactment of the hybrid mismatch rules with a deferred commencement date of 1 January 2019 allows taxpayers to review their hybrid arrangements and restructure them accordingly. Following concerns from industry regarding the potential application of the general anti-avoidance rules in Part IVA in this context, the Commissioner issued practical compliance guide PCG 2018/7 “Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 and restructures of hybrid mismatch arrangements” on 25 October 2018.

The PCG is effective from 24 August 2018, being the date of enactment of the hybrid mismatch rules and applies to restructuring arrangements entered into before and after that date. Guidance from the Commissioner is certainly welcome; however, beyond the useful examples in the PCG, we query how valuable the guidance really is. The PCG provides guidance by outlining restructuring that the Commissioner considers to be low risk and is framed in broad language. The Commissioner says that a low risk restructure will usually be characterised by the following features:

- There is no change to the entities or jurisdictions of entities involved under the replacement arrangement (in general terms);

- The original arrangement prior to the restructure would not have attracted the application of Part IVA;

- The replacement arrangement on a stand-alone basis would not attract the application of Part IVA (presumably disregarding the restructure);

- The restructure and replacement arrangement are effected in a straightforward manner; and

- Both the restructure and replacement arrangement are implemented in a commercial manner reflecting arm’s length conditions.

It seems odd that the Commissioner has not in his PCG appeared to have given any regard to the eight factors in section 177D(2), which are required to be considered in any examination of whether Part IVA applies to a scheme.

Notwithstanding the above comments, what we do know is that the hybrid mismatch rules are a potentially far reaching set of integrity measures, with their own special integrity measure in Subdivision 832-J. Any sensible taxpayer should be reviewing its existing hybrid arrangements which will require support of foreign tax counsel. Taxpayers may need to restructure arrangements where adverse impacts are identified through review, but the restructure steps will also need to be considered in the context of the general integrity measures in Part IVA.

Please contact Gilbert + Tobin if you would like to discuss how the hybrid mismatch rules may apply to you.

Visit Smart Counsel