So asks a recent Oxford Internet Institute study of the impact of AI on unpaid work (Vili Lehdonvirta, Lulu P. Shi ,Ekaterina Hertog, Nobuko Nagase,Yuji Ohta). The study compared the views of experts in the UK and Japan. While unpaid work is disproportionately performed by women in both countries, there were significant national differences in views about the impact of AI in the domestic sphere, apparently driven less by the technology itself and more by embedded societal attitudes.

Am I replaceable at work?

You don’t have to look far to get a sense of the escalating panic about whether our jobs are safe from replacement by artificial intelligence: such conversation has become a prominent fixture of public discourse, be it politics, academia or TikTok:

an Oxford university study in 2013 estimated that 47% of employment was replaceable by computers .

In 2017, McKinsey Global Institute published a study that estimated that about 50% of global work activities could be automated by employing existing technology.

In its 2020 ‘Future of Jobs’ report , the World Economic Forum estimated that automation could result in the displacement of 85 million jobs by 2025.

Technology has, is and will continue to replace human labour. Not surprisingly, this has given rise to a great deal of discussion around the extent to, and speed with, which this should happen and whether there should be controls on this process.

ChatGPT had some comforting words for us: “Instead of worrying, consider taking a proactive approach to position yourself for success in a technology-driven world” easy for it to say - it’s a machine-learning algorithm!

There is merit in this: perhaps the narrative should shift away from denial towards adaptation. By expanding our skills base, society will reduce the risk of creating Keynesian “technological unemployment” , that is, short-term unemployment resulting from technological advancements that displace human labour.

So, no - we shouldn’t panic, but we should be proactive in discussing and understanding how technology can be used to improve living standards and achieving a life-work balance.

Am I replaceable at home?

As the Oxford study notes that, without much fanfare, “robots for domestic household tasks, largely comprised of robot vacuum cleaners and floor mops, have become the most widely produced and sold robots in the world."

However, in considering the impact of AI on our lives, the Oxford study points out that very little thinking has been given to the impact of AI on unpaid work in the home - i.e. what will be the impact of the ‘life’ side of the (paid) work/life balance?

While it seems routine, unpaid work is just as important for the proper functioning of the household and society as paid work:

In 2021, the OECD estimated that UK citizens aged 15-64 spend about 43% of the time spent on work and study doing unpaid domestic work .

Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic & Social Research found that unpaid domestic work takes up almost 21 hours a week .

If Australians are spending between 3-4 hours per day on unpaid work, why shouldn’t we focus our attention on the extent to which these tasks are replaceable by technology?

Outcomes of the Oxford study

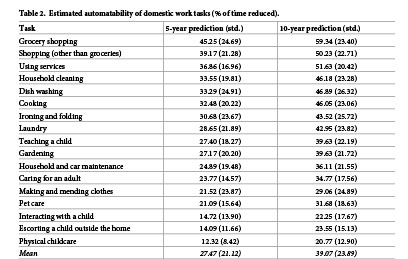

In the study, a panel of experts - being business professionals, research and development technicians, and academics - from the United Kingdom and Japan, on average, estimated that 27% of the time spent undertaking domestic tasks will be automatable within 5 years. This number grows to 39% within 10 years.

The study noted that this was consistent with studies of the potential impact which AI would have on paid work.

At first blush, these statistics show a future that appears scarily reminiscent of a Black Mirror episode. But before we start panicking about robots replacing parents as primary caregivers, the study gives an indication of the magnitude of the possible labour savings at home. As set out in the table below, the study also found variability in the degree of substitution across different household tasks:

This also could be seen as consistent with the thesis applied in paid work that “it is ‘routine’ work [that will be] more susceptible to automation than ‘nonroutine’ work; complex problem-solving and communication tasks have been singled out as particularly resistant to automation.” But the Oxford study posits a deeper sociological (or ‘more human’) explanation as to why we would be happy for robots to take out the garbage but not raise our kids:

the bulk of the experts’ written explanations for why care work was difficult to automate actually focused on constraints that were not technical in nature, such as the social acceptability of delegating childcare to machines, its developmental impacts on the child, and its privacy implications. I consider this to be the very last thing society will ever accept as suitable for automated services, wrote one. The opinion of the child was also mentioned as a factor (though not the opinion of elderly adults).

Gender and national differences

Technology that lightens the domestic load should be encouraged as it enables people - particularly women as they disproportionately carry unpaid work - to spend more time doing things which may have more financial or personal reward (even if it is still on an unpaid basis).

The Oxford study notes that domestic automation could free up to 5.8% of women in the UK to take up full or part-time employment. It is also estimated that domestic technology would allow Japanese women in prime working age to increase their labour market participation rate from 72.8% to 80.8%.

However, the Oxford study found significant differences in views about the impact of automation between the UK and Japan:

In the paid work environment, ‘technology replacement fear’ is much higher in the UK than Japan. 63 percent of British respondents agreed that “robots and AI steal peoples’ jobs”, but only 23 percent of Japanese respondents agreed. And while 91 percent of UK respondents agreed that “robots and AI are technologies that require careful management”, only 67 of Japanese respondents agreed

In the unpaid work environment, UK-based experts on average believed that automation could replace more household labour than their Japanese counterparts did: their average predictions were 42 percent vs. 36 percent in Japan in ten years, and 32 percent vs. 24 percent in five years.

There were also pronounced gender-related differences about the impact of automation on unpaid work between the UK and Japan. In the UK, male experts were significantly more optimistic about technological potentials than were female experts, which is in line with the finding that men tend to be more optimistic about technology in general. Yet in Japan, the situation was opposite: male experts were less optimistic than females.

The Oxford study noted that:

Possible interpretations could be sought from Japan’s especially stark gender disparities and how that influences’ experts’ perceptions. It would not be uncommon for Japanese men in expert positions to have almost no personal experience of major domestic work tasks, which they delegate instead to their wives.

In Japan, the average working-age man’s time spent on domestic work is only 18 percent of a working age woman’s; in the UK, the figure is 56 percent. This flows through to adoption rates for labour saving appliances: in Japan, female, but not male, income is positively associated with dishwasher adoption, but no such difference is observed in the adoption of air conditioners, PCs, or cellular phones.

But before you conclude that UK males are less irredeemably sexist than Japanese men, the Oxford study also notes:

the marginalisation of women in the development of technologies has steered technologies available in the market towards directions that do not always serve women’s interests. One recent example of this may be how the kind of digitalized home schooling implemented in the UK during the pandemic meant that many carers, especially women, had to double as unpaid teaching assistants and IT support persons on top of their normal duties—with detrimental consequences to their ability to succeed in paid work careers.

So - what is to be done?

Why should policy makers pay more attention to the impact of automation on unpaid work? Three reasons:

the imperative to undertake domestic work isn’t likely to decrease anytime soon: homes will always need cleaning and food will always need cooking. More vitally, the aging population and increasing prevalence of serious illnesses will necessitate a greater demand for carers.

from a government fiscal perspective, we have likely reached the limit of how much people can reasonably be financially compensated to undertake unpaid work, for example, carers allowance or parental leave. If we are not able to increase the financial reward for such work, the only practical alternative is to substitute technology for labour.

how we allocate and recognise responsibility for unpaid work also says a lot about us as a society, with the persistence of embedded gender biases in unpaid work.

A sophisticated regulatory framework has developed over time around the use of technology in workplaces particularly in relation to worker safety. More recently we have seen regulatory frameworks being developed in relation to digitisation and AI, for example privacy laws, data ownership and use of incidentally collected data, and the right to the financial rewards of monetisation of this data.

The potential for labour saving technology in the realm of unpaid work raises the question of whether there are lessons to be learned and applied from these parallel developments in paid work. Should we accept the inexorable rise of technology without any constraining factors? Whilst we openly acknowledge the benefits of technology and AI and the potential for freeing up time for more productive or enjoyable activities, isn’t it equally important to ask what possible harms may arise? Are the protections being developed in respect of technology and AI in the workplace and social activities relevant or appropriate in the context of unpaid labour? Is there a risk that time saving technologies (even as innocuous as on line shopping and delivery) will deliver enormous amounts of data to the service provider or the manufacturers of time saving processes and equipment that could lead to inappropriate access and use of personal information? How do we protect rights such as privacy and commoditisation and monetisation of information?

But perhaps more so than in paid work, questions around the automation of unpaid work are reflective of a deeper existential angst: to what extent are we replaceable by the very robots we have created to help us live more optimally? The answer to this question turns on what unique value humans produce and the extent to which robots can and should replace it.

To conclude, we asked ChatGPT what are the risks to society of AI being used to replace unpaid labour? Somewhat self-centredly, it responded that this would “create a risk of dependence ”, which could leave us vulnerable to disruptions in the event of technical failuresa fine example of technology protecting its own interests!

Peter Waters

Consultant