Large internet platforms and the broader adtech industry have been under considerable global regulatory scrutiny over their data privacy practices while the underlying providers of internet connectivity, Internet Service Providers (ISPs), have largely been on the sidelines. However, the staff of the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has recently fired a shot across the ISPs’ bows.

In August 2019, the FTC issued orders to six ISPs and three ISP-affiliated ad networks covering approximately 80% of the fixed residential internet market to gather information on their data collection and use practices. The FTC released its report over two years later in late October 2021.

Are ISPs in a unique position to collect data?

The FTC notes that ISPs are small players in a nearly $455.30 billion global digital advertising industry. For example, in 2018, Verizon, the largest US ISP, received just 3.4% of the digital advertising spend in the United States, compared to the three largest players - Google, Facebook, and Amazon - which received almost two-thirds of U.S. digital advertising spend.

But the FTC comments that “[d]espite ISPs’ relative size in a market dominated by Google, Facebook, and Amazon, the privacy challenges that permeate the advertising ecosystem may be amplified by many of the ISPs in our study in a few respects” (our emphasis).

Why? For two reasons according to the FTC:

First, as ISPs are the providers of ‘fee-for-service’ global connectivity to customers, legitimately they need to collect a wider range of information about their customers such as name, address, credit history etc than the ‘for free’ over-the-top (OTT) providers. However, more tellingly for the FTC, in the course of providing their core internet access services, ISPs also become passive collectors of comprehensive information about their customers’ use of the services. This means that:

"any of the ISPs in our study have access to 100% of consumers’ unencrypted internet traffic. In contrast, only Google has a presence on 75% of the top million websites, with the others having a presence on no more than 25% of the top million websites. Some have argued that, with the rising adoption of encryption by websites and prevalence of VPNs, ISPs do not have access to as much consumers’ browsing history as large ad networks like Google, Facebook and Amazon. However, even with encryption, many ISPs in our study continue to store the IP addresses that their customers access and thereby collect the domain names of the websites they visit."

Second, ISPs are more readily able to track “cross screen” usage:

"a significant number of the ISPs in our study can track consumers persistently across websites and geographic locations. By virtue of their access to consumers’ internet traffic through the provision of internet services, these ISPs are capable of persistently tracking consumers by appending undeletable identifiers to consumers’ internet traffic, and at least two, in fact, do. Commonly used measures for protecting privacy, such as switching browsers and devices, enabling “private browsing mode,” or deleting cookies, did not prevent these two ISPs from continuing to persistently track their subscribers. Additionally, mobile internet providers can target consumers based on their real-time and historical location through the use of cellular tower data, even when location tracking on their phones is deactivated."

How are ISPs using their position to leverage data?

The FTC considers that ISPs are enlarging and leveraging data they collect in two ways:

Vertical integration

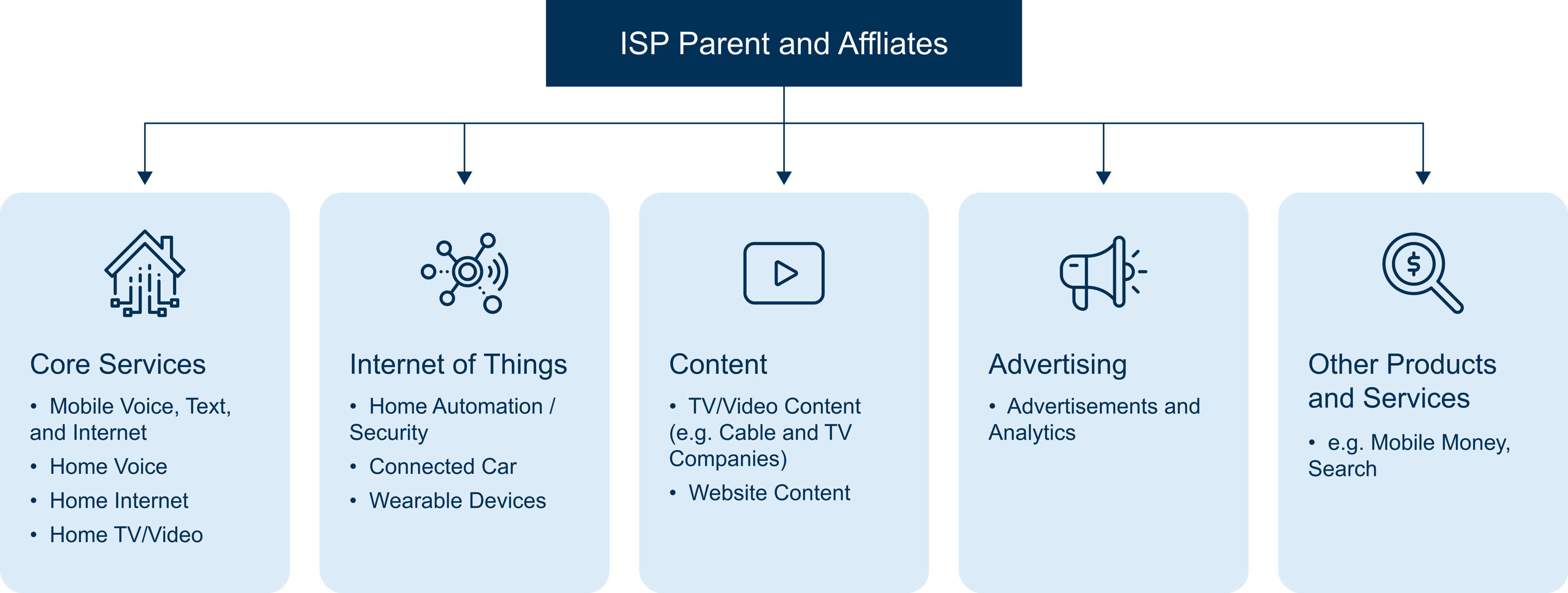

ISPs are using the data they collect for core services in ways unrelated to the core services, and they are combining the data from core services and vertically integrated non-core services. ISPs have evolved beyond providing internet access to consumers. ISPs often provide bundles of services such as internet, video, and voice, connected cars, home security, or mobile money. In addition to providing internet, voice, and cable access, ISPs, as gatekeepers to the internet, have also become players in content creation and ad monetisation.

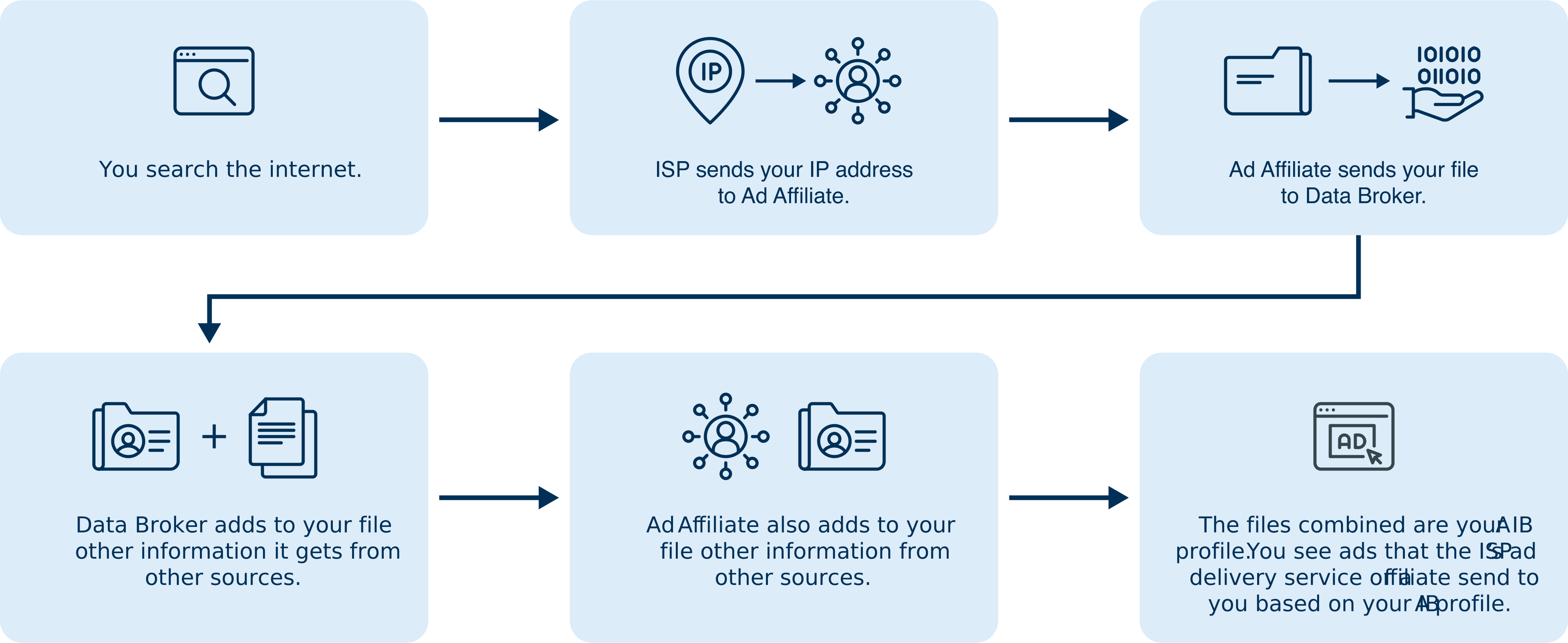

Data brokers

ISPs are able to buy demographic information from data brokers and combine this information with other data collected. For example, ISPs can combine consumers’ personal information, app usage and/or browsing information for targeted advertising purposes. ISPs are able to collate such information into “segments” such as “pro-choice”, “African American”, “investor high-value” and “golf carts and gourmets”. ISPs can also leverage location information in connection with their aggregated business insight reports. For example, using location information, one ISP surveyed by the FTC revealed that it could inform a retailer that 35% of visitors to a particular store were Hispanic-Latino with household incomes between USD 40 – 74.5K.

What are the FTC’s privacy concerns?

The report observes that:

- Consumers often need to ‘opt-out’ or click on ‘do not sell’ options but they do not fully understand how ISPs use their information. One ISP surveyed in the FTC report explained that a consumer would need to make 9 selections to fully protect the privacy of their personal information. Such a cumbersome process is often accompanied by lengthy disclosures next to opt-out choices. The FTC report found that less than 2% of subscribers actually opt-out and exercise their ‘choice’.

- ISPs in the study were ‘opaque’ about the uses to which information was put. While ISPs’ terms stated that they “will not sell your personal information,” the FTC considered that the ISPs give insufficient information to consumers regarding the other ways that their data can be used, transferred, or monetised outside of selling it: “consumers may not understand the process through which these ISPs buy consumer information from data brokers, use it to infer additional information about them, categorize them into segments, and serve targeted ads to them on behalf of third-parties.”

- Several ISPs gather and use data in ways consumers do not expect and could cause them harm – such as collecting browsing data, TV viewing history, email searches, data from connected devices and location information which could be used by property managers or bail bondsmen for discriminatory purposes.

- Although many of the ISPs in the study purported to offer consumers access to their information, the FTC considered that “this offer is largely illusory, given that the information is either indecipherable or nonsensical without context.” The ISPs generally provided good information about billing, but generally provided no specifics on the other information they collected and used, with one exception:

"One ISP not only lists specific background and demographic information, but provides concrete examples of inferences the ISP makes (e.g., “Low Likelihood to Add internet” but “High Likelihood to Add TV”). Similarly, one ISP allows consumers to see the segments associated with the cookies on their browser. However, some fields are quite opaque and do not provide any information about what the ISP knows. For example, an ISP might label “Religion Code” as “54,” “Race Code” as “W”…"

A regulatory mash-up

The FTC report does not specify remedies – that’s for another inquiry.

In some ways the more interesting takeout from this report is that it seems to be another example of the trend amongst regulators to fashion a ‘theory of everything’ for regulation of the digital domain that mashes up competition law, consumer protection, and privacy regulation:

"[O]ur report is limited to the privacy practices of ISPs. While this report does not discuss competition issues between ISPs or their vertically-integrated entities, the intersection of the two is relevant to this discussion. For example, market power may enable violations of consumer protection laws and exacerbate the effects of those violations. Consumer protection violations, in turn, often have detrimental effects on competition. Companies may gain market share through deceptive reassurances on privacy. As such, competition issues will continue to inform the Commission’s approach to privacy in this space."

Visit Smart Counsel