The European Union is betting big that ‘Open Innovation’ will be the engine of growth for the digital economy:

“We believe that the intersection of mega-trends such as digitization, mass collaboration, and sustainability needs is creating a unique opportunity to enable an explosive increase in shared value due to innovation…. In today’s complex world, experiments simply cannot be conducted in isolation. Collaborative research will accelerate the innovative process and improve the quality of its outcomes. While closed-world innovation will not disappear, it will be dwarfed by the efforts of teams that enable a wide spectrum of stakeholders to take on active roles.”

Australia clearly lags in innovation. Australia ranks only 23rd for overall innovation in the 2020 Global Innovation Index. So, does Australia need a big dose of Open Innovation? What policy and legal changes would be needed to shift from the historic model of ‘closed innovation’?

What is Open Innovation?

The academic to whom the concept of Open Innovation (OI) is attributed, Henry Chesbrough, says there are many definitions of OI and the definition is continuously changing. He identifies what OI is not:

“Some claim it works just like open source software. It doesn’t. The business model for innovation is a key part of open innovation. Others think that it is just supply chain management. It isn’t. Open innovation involves many other actors that fall far outside traditional supply chains (such as universities or individuals), and these participants in open innovation can be influenced, but often are not actually directed or managed. Some claim it is user innovation. It’s not. The user is certainly very important to open innovation, but so are universities, startups, corporate R&D and venture capital.”

OI can be thought of as the sharing of information, data and IP between different parties to lead to new innovations and developments, rather than organisations being solely self-reliant on their own knowledge, sources and resources to innovate. OI opens more opportunities to allow organisations to capitalise upon the latest and greatest inventions as part of their own business models, rather than being constrained by the resources available to that organisation alone.

Thus, OI is the antithesis of the traditional business model of the vertically integrated firm where internal R&D activities lead to internally developed products that are then distributed by the firm.

OI flows in two directions: “outside in”, where external ideas and technologies are brought into the firm’s own innovation process; “inside out”, where un- and under-utilized ideas and technologies in the firm are allowed to go outside to be incorporated into other firms’ innovation processes.

As Chesbrough says, in an OI model, “the locus of innovation is the network”. OI swims, as it were, in two broader digital trends:

- it is increasingly uncommon for one firm to account end to end for a technology solution. While the end product might be integrated, behind the single user interface will be functional components and elements provided by different vendors. The typical construct of an IoT product is a good example of this;

- data collected by a single firm has more value when shared, combined with data from other firms or used by other firms in ways which the collecting firm cannot use the data.

It should not be underestimated how much OI can disrupt the traditional business model and the legal models which gave expression to and protected that model. Almost since companies were developed as separate legal personalities, the legal boundary of the corporation represented the outer limits of knowledge sharing, and that boundary was ‘girt’ with an array of protective laws, including intellectual property, confidentiality, trade secrets and employment law. In that ‘closed innovation’ model, the task of internal and external counsel was to ensure this boundary was impervious except in highly defined circumstances such as a JV, a franchise or a distributorship.

Under an OI approach, the legal boundary of the company still matters, but now information, ideas, effort and IP pass back and forward across the boundary. This can happen with much fluidity and not necessarily a lot of predictability or control over the forum – such as a Zoom call with sharing of screens. The management of boundaries requires active decision-making to identify and define activities allowing for a connection between the firm and the external environment. This is a much complex, strategic job than the ‘sovereign borders’ approach of old.

But how do we get there?

The European Commission has published a study to be conducted of SMEs to ascertain their understanding of OI and its relationship to IP.

The study found that SMEs face four main obstacles to engaging in OI projects or maximising their commercial opportunities:

1. SMEs do not think strategically about their IP portfolio

Often, SMEs have a basic understanding of some IP essentials. For example, they may know to register their logo as a trade mark or to protect a lucrative invention through a patent. However, for most SMEs, their knowledge of and investment in IP ends there. Formalising an IP portfolio can also be seen as expensive, unnecessary, and low priority to an organisation unless their business is heavily reliant on IP.

2. SMEs struggle to articulate or specify their Soft-IP

As the nature of business and technology has evolved, so too has the type of IP that an organisation holds. SMEs may not even realise that certain business processes, know-how or other ‘Soft-IP’ is actually IP at all, let alone put in place robust protections for the use and management of such IP. Additionally, the study found that businesses struggle to identify and clearly define or articulate Soft-IP in their commercial negotiations and collaboration opportunities, opening these businesses up to the risk that a third party might claim other IP owned by the business as their own. IP literacy, therefore, is vital to ensure that the value of a business is protected.

3. SMEs lack IP negotiation skills

The study also identified that SMEs are inexperienced with IP risk assessments, which impact their ability to negotiate favourable outcomes in commercial dealings and can lead to the organisation agreeing to unfavourable agreement terms.

4. SMEs face challenges due to organisational asymmetries

Finally, the study found that SMEs experience organisational asymmetries with their counterparties, particularly where the other side has a robust IP portfolio and strong understanding of how to use their IP strategically.

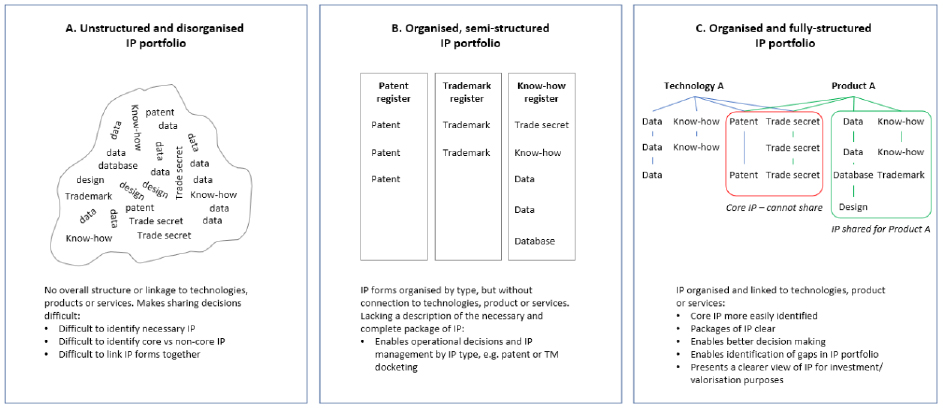

The following diagram from the EU report, while ‘busy’, usefully shows the different ways that a business could organise their IP portfolio:

In our experience, Australian businesses tend to organise their portfolio similarly to categories A and B (in line with the findings of the EU study). In the context of a deal, lack of structure and organisation of an IP portfolio could lead to:

- lack of certainty that the IP used by a Target is actually owned by that Target. This could result in unfavourable warranties or indemnities included in purchase agreements, changes in price to account for uncertainty, or potential future claims of IP infringement or litigation. Tracing back the origin of different forms of IP to confirm chain of title can also be a costly exercise in the due diligence process and drag out the timeline of a deal; and

- the inability to carve out parts of the business that are for sale or intended to be transferred to the Target, and IP that is to be retained by the Seller. This could lead to an organisation revealing confidential information or providing access to IP that they did not otherwise wish to include in the transaction.

By structuring an IP portfolio similarly to diagram ‘C’, organisations can tie various forms of IP to different products and services. This gives an organisation a competitive advantage, as they are aware of what they can and cannot share in their commercial dealings and are able to negotiate more specific and favourable IP terms.

OI vs IP?

Chesbrough argues that it is oversimplistic to treat OI and IP law as being diametrically opposed to each other: “within an open innovation framework, IP is not a fence preventing others from making use of a protected technology; but rather a bridge to collaboration with other firms and organizations.” Without IP protection firms would face a ‘disclosure’ problem in having conversations about co-operation in the first place.

True enough, but when IP is to be used as a strategic tool of collaboration, not just of protection and compliance, a lot more thought and organisation needs to go into the IP arrangements and how they will fit within an OI model.

A recent study identified that OI projects currently have a high failure rate due to the following factors:

- Lack of clear vision or goals from collaborating with others;

- Lack of structure and planning;

- Poor resource allocation;

- Financial pressure; and

- Risk of legal trouble (specifically IP related) and risk of crucial company information being mishandled or abused.

The less an organisation has properly planned for OI collaboration, the more likely that collaboration is to fail. This includes the extent to which a firm has thought about how they want to protect and use their IP portfolio. A firm with a robust system for protecting their IP and ability to delineate certain types of IP from others in accordance with the purpose of the collaboration is far less likely to open themselves up to the risk of legal trouble down the line.

Although OI may presently have a higher failure rate than expected, it is not a new or novel concept. Research institutes and universities have been sharing information and IP for decades and fully embrace the idea that IP owned by one organisation can and should be made available to others in order to progress research as a whole. Impressively, universities and research institutes are able to manage and track their IP portfolios to such a degree of precision that they can clearly identify and trace back the owners of genetic material used in live animals such as cross-bred mice (even when the mouse is the progeny of multiple strains of other genetically modified mice).

Whether you believe that OI is the way of the future or not, there are a few things that organisations could do today in order to position themselves well in negotiations, mergers, acquisitions or other commercial opportunities. The first step is to take a critical look at the organisation’s IP portfolio and protections. For example:

- Break down the organisation’s IP into different categories e.g., brand by brand, different types of software or product lines on offer. Can the organisation neatly identify which IP it holds that links to that category?

- Consider whether registrable IP (e.g., logos, inventions, designs) have the maximum protection available under Australian law (i.e., has all registrable IP been registered?);

- Do employees create IP? Do their employment contracts contain active assignment and vesting provisions (e.g., ‘Employee assigns all IP to Company) or inactive assignment provisions amounting to nothing more than a promise? (e.g., ‘Employee agrees to assign); and

- Does the organisation have control over who accesses its confidential information, know-how or trade secrets? Does its employment and contracts with third parties have robust confidentiality provisions?

The suggestions above might sound like a lot of work and expense - however, as the EU study shows, going to the effort to protect and categorise IP enables greater opportunity for OI and other commercial opportunities.

Read more: Building stronger intellectual property strategy capabilities

KNOWLEDGE ARTICLES YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN:

Visit Smart Counsel