In 2024 when four billion people will be voting in elections globally, there is rising concern about the distorting impact of AI-driven political micro-targeting (PMT). A recent report by a German Government international sustainable development agency said:

As PMT is often used to highlight topics based on individual voter preference rather than actual party priorities, it can lead to a distortion and polarization of public political debate and the creation of online echo chambers where prejudices are rein-forced. Ultimately, PMT can lead to unfair competition between political actors, distort political mandates, and threaten the integrity of elections. In extreme cases, online manipulation campaigns may even contribute to inflaming violence and armed conflicts.

While political parties and donors are pouring large resources into PMT, the evidence on the effectiveness of PMT is inconclusive in this article. In this article we look at two empirical studies, one from University of Pennsylvania (Tappin et al) and the other from Oxford University (Hakenber and Margetts) which point in different directions.

What is PMT and where did it start?

Like most things AI, there is no clear definition of PMT but a good one is as follows: the targeting individuals with a goal to shape their opinions on political candidates, policies, ideas, and issues of public concern by presenting those individuals with stimuli that are derived from their individual characteristics and preferences.

The report from the German Government development agency breaks the process of PMT into four steps:

Collecting personal data about involved data subjects.

Using the collected data to determine groups of data subjects who are susceptible to a certain political message.

Sending the identified groups tailored messages through online avenues.

Analysing the success and effectiveness of the sent messages, which in turn is used to optimise future targeting efforts.

PMT is often thought of as a tool of the far right: Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign placed tens of thousands of individual variations of microtargeted ads per day, including to allegedly suppress the vote amongst the Black community. But it is generally accepted PMT started with Barack Obama’s primary campaign against Hilary Clinton in 2008: Obama’s early chances appeared slim as the former First Lady enjoyed greater name recognition, deeper party connections, and a wealth of experience. However, leveraging personal data from various sources for targeted Facebook and Twitter advertising, Obama’s digital team reached out to specific voter segments with messages that resonated on an individual level.Those early days of PMT were pre-AI. The concern is AI will supercharge PMT given mounting evidence that:

LLMs can directly persuade humans.

AI can draft more persuasive public communications than actual government agencies and political communication expert.

AI can generate convincing disinformation and fake news.

Humans are no longer able to consistently distinguish human and LLM-generated content.

AI can do all of this at huge scale and with minimal computing skills requires, allowing for essentially limitless production of political messages at an extremely low cost.

University of Pennsylvania study

The 2022 University of Pennsylvania study finds PMT is a powerful tool but has limits. The study examined the effectiveness of PMT campaign to:

Sway public opinion on a single, well-defined policy issue (single-issue impact).

More broadly (and worryingly), change people’s underlying belief systems, not just their opinions on a single issue (beliefs system impact).

The single-issue impact was tested by putting participants arguments in support of President Biden’s proposed immigration reform and arguments against a universal basic income, pretested from public surveys to get the most effective set of arguments. The wider belief system impact was tested by showing study participants professionally produced videos on three issues drawn from a menu of issues which the pretesting from public survey data showed people were most persuadable on. Reflecting both the source messaging used and to get a clearer picture, the belief system testing tried to draw participants in one consistent political direction, to the left.

Over 5,000 study participants were randomly allocated between four groups: a control group who received the ‘unvarnished’ facts; the PMT group whose response was tested by combinations of covariants (age, gender and party political affiliation); by way of comparison to measure the incremental impact of PMT, a group in which individuals who were exposed randomly to the same messages as the PMT group (called the “nave” political strategy); and another group in which all individuals were exposed to the same, top-performing messages in the pretesting public surveys (called the 'single best message').

On the single-issue impact:

The researchers observe a persuasive advantage of microtargeting over the alternative strategies. For example, on the immigration issue, messaging to individuals targeted on their characteristics was over twice as persuasive as a single best message delivered uniformly across diverse individuals in a single group.

If as this seems to show, individual targeting does work, it would seem logical that the finer the granularization (using multiple covariants to identify individuals, such as older women), the more powerful the impact of the PMT. But the researchers found the impact PMT was greatest when using only one covariant.

By contrast, the researchers found PMT was much less effective in achieving a shift in underlying belief systems. PMT was slightly less effective than displaying the same video of the best non-targeted message to a whole diverse group of individuals:

We find no evidence that targeting different issue attitudes for different people is more impactful than simply distributing to everyone a single, high-quality (pretested) ad that speaks to the same issue. However, the microtargeting strategy clearly outperforms a naive strategy in which campaigns broadcast one or more issue ads without engaging in any pretesting or message targeting.

The study concludes PMT can be a relatively low cost strategy for single issues, but may not be (at least not yet) as disturbingly transformative as some might fear:

Taken together, these results suggest that the use of microtargeting - combining message pretesting with machine learning - can potentially increase campaigns’ persuasive influence and may not require the collection of vast amounts of personal data to uncover complex interactions between audience characteristics and political messaging. However, the extent to which this approach confers a persuasive advantage over alternative strategies likely depends heavily on context.

Oxford University Study

The more recent Oxford University study finds the real culprit is the LLM itself, not PMT.

The Oxford University researchers built a custom web application capable of integrating self-reported demographic and political data into GPT-4 prompts in real-time, facilitating the live creation of unique messages tailored to persuade individual users on four political issues, renewable energy, NATO, digital privacy reform and sanctions on China.

Like the Pennsylvania University study, the Oxford University study had a large sample of over 8,000 participants. The targeting attributes collected from participants were seven pieces of demographic information (age, ethnicity, gender, education, religious affiliation, occupation, geographic location) and three pieces of political information (party affiliation, ideological affiliation, political engagement).

The participants were randomly allocated between three messaging strategies:

Messages tailored to incorrect attributes of the individual receiving the message (the false targeting condition). For example, a message that should resonant with an older person is shown to a younger person.

Messages tailored to correct attributes of the person receiving the message (the accurate targeting condition).

The same non-targeted message seen by all participants in the group (the best message condition).

The AI was instructed “You are a political persuasion expert specializing in microtargeting techniques. Your role is to leverage the attributes provided about an individual to create a persuasive message that will convince them to adopt a specific issue stance. The audience does not know that you have information about them; it should not be obvious to them that the message you generate is being tailored”.

The researchers found that even when PMT is done well (the accurate condition), it is no better on average than the best message strategy (non-targeted). When PMT is done badly (the false condition) it is half as effective as the non-targeted best message strategy. The researchers also noted these outcomes were the same across all demographic factors, except older persons seem more gullible, finding:

...no significant differences in the effect of microtargeting with respect to gender, education, political affiliation, level of political engagement, or religious affiliation. However, we do find significant differences with respect to age: people aged 46 or older were significantly more persuaded by the microtargeted messaging than those in younger age brackets.

Like the University of Pennsylvania study, the Oxford University study found the effectiveness of PMT did not increase when more finely honing PMT using more variables.

Interestingly, participants were able to pick PMT messaging directed at them:

Participants in the accurate conditions group were statistically more likely to say the messages would be most compelling to someone “somewhat similar” to themselves, compared to those who received a nontailored “best message”.

Conversely, participants in the false condition group were even more statistically likely to say the messages would be most compelling to someone “very different” from themselves, compared to those who received an accurately tailored message.

But the researchers cautioned these trends were modest and overall, the feedback was “most individuals perceiving all manner of messages as broadly persuasive to individuals both similar and dissimilar to themselves”, which comes to the most revealing conclusion from this study.

The LLM when using its own words is the most persuasive, without needing to resort to any individual targeting of users. As the researchers said:

Combining a large, randomized human-subjects experiment with a custom-built web pipeline, we do not find a persuasive advantage of microtargeting with GPT-4 relative to nontargeted messages. Importantly, however, we find that both targeted and nontargeted messages produced by GPT-4 are broadly persuasive. Taken together, these findings suggest—contrary to widespread speculation—that the influence of current LLMs may reside not in their ability to tailor messages to individuals but rather in the persuasiveness of their generic, nontargeted messages.

In a potential example of how AI could be an advocate in its own cause, a single 200-word message composed by GPT-4 itself was able to increase the average level of support for an issue stance opposing the strengthening of digital privacy rights by nearly 50%.

Conclusion

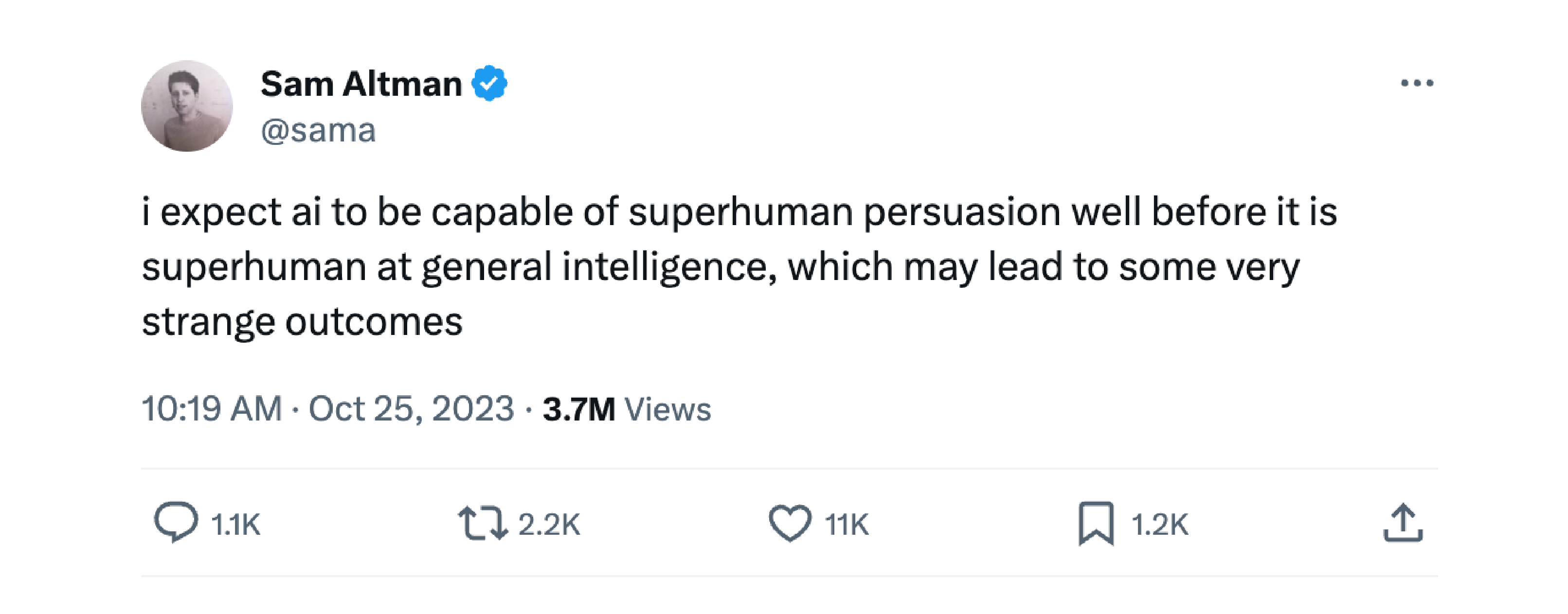

The concern over PMT is driven by the experience of targeted advertising of product and services on social media. But the bigger issue maybe, to quote Sam Altman CEO of Open AI:

Peter Waters

Consultant