In Part Three of our series on the tax angle to the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (the Commission), we observed that the most effective vigilance against self-interest and conflict will come from clients.

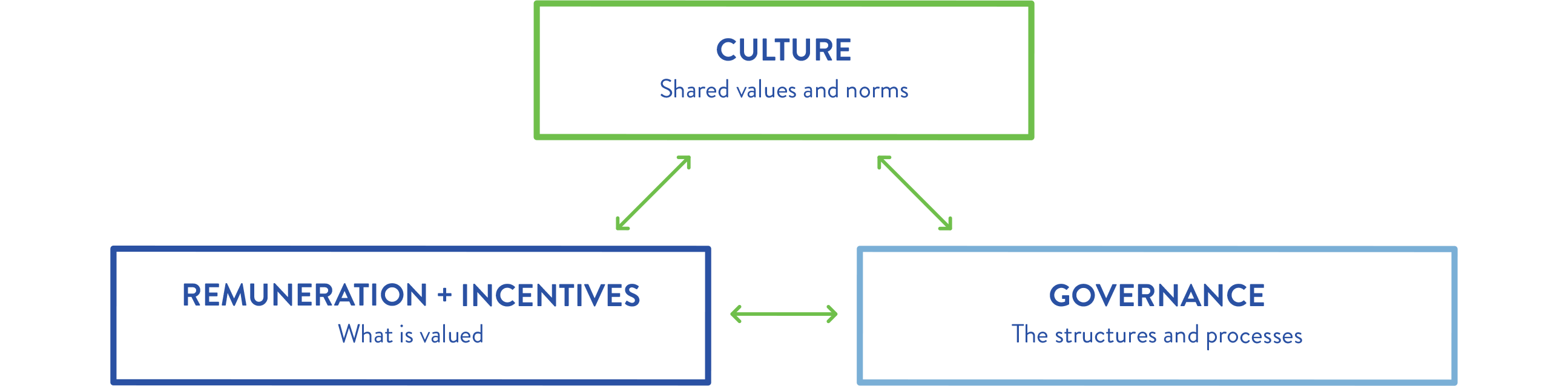

In looking to allocate blame, the Commission noted “close attention must be given to [the entity’s] culture, [its] governance and [its] remuneration practices”. “[E]ffective leadership, good governance and appropriate culture within entities are fundamentally important. … Supervision [by regulators] … requires attention to culture, governance and remuneration.” This is equally applicable to every industry, to every entity and in relation to tax policies.

In this Part, the final one in our four part series on the Commission’s final report, we look at tax governance strategies for clients.

Key takeaways and action items

- Taxes are what we pay for civilised society. Your tax strategies must conform to community standards, particularly the more significant that you are to that community.

- Refine variable remuneration of tax personnel to clarify that achieving tax metrics is not the sole or dominant basis for bonuses.

- Boards and senior management must be involved in tax policies. Processes must be established to elevate tax matters to Boards, with effective supervision. Live the policy.

Shifting sands

Tax practitioners in big corporates will be familiar with the refrain from tax regulators globally that they must “pay their fair share of tax” (never mind that corporates were paying the tax mandated by the law enacted or administered by the same people making such claims). Such claims saw “voluntary” payments of corporate income tax by Starbucks in the United Kingdom (albeit for two years only) and emboldened the annual publication of the “Corporate Tax Transparency Report” by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

These calls and changes, if cynicism and clever marketing are put aside, seem to demonstrate a shift in community standards.

The Commission recognises this in the context of certain conduct it examined: “the conduct has broken the law … [or] fallen short of the kind of behaviour the community not only expects … but is also entitled to”. The observation is made in the context of the significance of the financial services industries to the economy, but one could argue that the same observation could be made in relation to the collection of taxes, a significant aspect of the modern economy and society more generally.

Variable remuneration

The most publicised criticism levelled by the Commission was in respect of the relevant players’ greed: “… [In] almost every case, the conduct in issue was driven not only by the relevant entity’s pursuit of profit but also by individuals’ pursuit of gain, whether in the form of remuneration for the individual or profit for the individual’s business.”

It is likely that tax practitioners in corporates are not rewarded for specific tax outcomes, and it is also likely that the variable remuneration of such practitioners is a far smaller proportion of their total remuneration than those of other employees. In more sophisticated organisations, monitoring and managing tax metrics is a key role of tax practitioners.

Tax governance policies

Responsibility

The Commission leaves no doubt as to who is responsible for misconduct – “boards and senior management”.

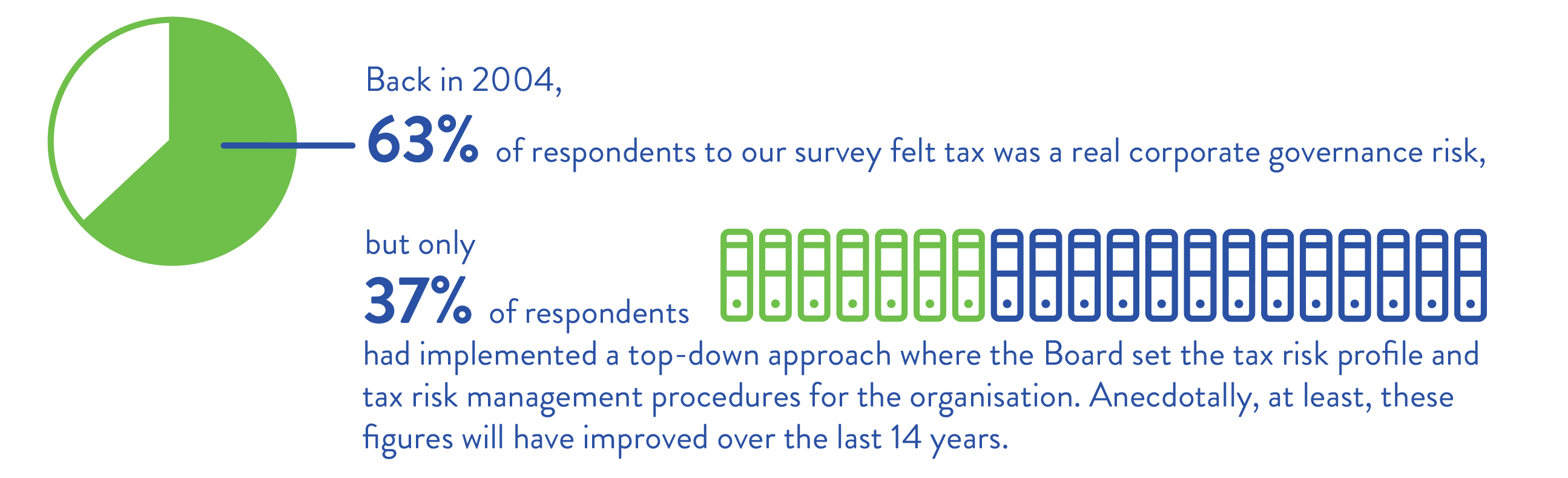

Since the ATO first released its views on tax risk management and its expectations that corporate boards would be involved in that governance back in June 2003, followed shortly thereafter by Gilbert + Tobin’s survey in early 2004 to “gauge corporate Australia’s attitude to the growing importance of tax risk management”, tax governance policies have proliferated through leading Australian companies, spurred by experiences drawn from overseas, particularly the United Kingdom.

Living it

The ATO is already doing this. It notes on its website, “When appropriate we assess the tax governance processes of large business entities that we have under review.” The ATO typically includes questions regarding a taxpayer’s tax governance in its “streamlined assurance review” questionnaire that is part of its Top 1,000 Tax Performance Program. In a recent public forum, the ATO also noted (albeit in relation to a different subject) that it found, in some of its reviews and audits, that taxpayers had policies or guides but could not demonstrate how to apply them in practice.

Supervising governance

It is useful for boards and senior management to consider the questions posed by the Commission as it applies to their organisation’s tax governance:

1. Is there adequate oversight and challenge by the board and its gatekeeper committees of emerging risks? Organisations have significantly differing attitudes to tax, with some organisations giving tax personnel a seat at the board table. But as the Commonwealth Bank example cited by the Commission demonstrates, the Board’s active challenge of matters presented is essential.

2. Is it clear who is accountable for risks and how they are to be held accountable? An example that often arises is the tension between the tax personnel and the legal personnel within an organisation, especially as matters become more contentious, more likely to lead to litigation.

3. Are issues, incidents and risks identified quickly, referred up the management chain and then managed and resolved urgently? Human nature plays a strong role in preventing full, frank and prompt disclosure of any issues, and tax personnel who may feel they were involved in the implementation of a tax strategy now under challenge may feel disinclined to move it up the management chain quickly.

4. Is there enough attention being given to compliance? Is it just box-ticking?

5. Do compensation, incentive or remuneration practices recognise and penalise poor conduct? It is not just about what is done, but how it is done.

5. Do compensation, incentive or remuneration practices recognise and penalise poor conduct? It is not just about what is done, but how it is done.

The Commission’s observations on the opposition of boards to a proposal by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority to require the establishment and maintenance of a sound risk management culture is telling. But unlike other regulators, the ATO is not shy about taking active steps to review governance and any failures in governance that are found are likely to find their way to bottom line performance.

Interestingly, even back in 2004 when we conducted our tax governance survey, over half our respondents felt there was a case for having a member of the Board with some tax knowledge or experience! The tax world has changed so much in that time, in terms of the demands placed on tax personnel, the shifting sands of perception and community expectations, the increasing complexity of domestic and international tax laws and the increased regulatory activities of the ATO. It seems even more important than ever before for Boards to be active in the setting and supervision of tax matters and tax governance policies.

Visit Smart Counsel