The global shift towards a greener and more sustainable future is now well and truly underway.

As countries the world over embrace the vision of a net-zero economy, the Australian Government has taken a critical step towards the development of a leading offshore energy industry by the introduction of the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Bill 2021 (the Bill) into the Commonwealth Parliament on 2 September 2021.

The introduction of the Bill is a crucial first step in the establishment of a comprehensive regulatory regime and framework for the licensing and eventual development and construction of offshore renewable energy generation and transmission infrastructure (OREI). Tabled by the Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction, The Honourable Angus Taylor MP, the Bill aims to “unlock a wave of new investment” in Australia’s offshore electricity sector and harness what has been described as one of the “big three” streams of clean energy set to drive the renewables transition, alongside solar and onshore wind assets. We explore the Bill in detail later in this article.

Whilst offshore wind energy has found itself an industry becalmed in Australian waters, the introduction of a new licensing and regulatory regime for the full life-cycle of OREI projects, as provided for in the Bill, promises a transparent pathway to the future, hopefully de-risking and reassuring sponsors, investors and financiers.

Once enacted, this legislation will hopefully act as a catalyst in accelerating the development of Australia as a destination jurisdiction for investment in offshore wind energy. According to recent data, that market spurred more than US$500 billion worth of investment in 2020 alone. More importantly, the Bill signals that Australia is awake to all aspects of the renewable economy and that its world-class and abundant natural wind resources are now open for business.

The role of offshore wind in the clean energy transition

Currently, offshore wind accounts for only a fraction of global energy supply. However, offshore wind is set to be a “superpower” of the next generation, with the number of projects in development forecast to triple globally throughout the 2020s.

According to studies commissioned by the International Energy Agency, the global offshore wind market experienced steady, year-on-year (YoY) growth of 30% between 2010 and 2018. In 2020, the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC) reported that the wind energy market recorded its “best year in history”, experiencing an astonishing YoY growth of 53%. That figure becomes even more impressive in the context of a global pandemic, and the still unperturbed demand for wind energy that saw a colossal 92GW of new installations worldwide.

Now, with more than 740GW of wind power capacity installed worldwide, the greenhouse gas emissions benefits can be seen and are immense. Recent estimates identify that harnessing this energy avoids over 1.1 billion tonnes of CO2 globally - a figure comparable to the annual carbon emissions of the continent of South America. Whilst the carbon footprint advantages of wind power are established, the rapidly maturing market for offshore wind energy is abundant with both investment and, more broadly, economic benefits and opportunities.

Investment in, and development of, OREI, specifically offshore wind projects, is forecast to quadruple in the next four years globally. Almost 24GW of new installations are forecast for 2025 alone. With increased offshore wind production comes a commensurate (and rapidly increasing) prominence in the share of total wind production (both onshore and off). Currently, offshore wind accounts for a steadily growing 6.5% of share of all global wind energy production. By the time 24GW of energy is produced offshore, in 2025, this number will leap to over 20%.

The importance of wind power to the overall carbon-neutral goal and broader renewables push cannot be understated. Earlier this year, the GWEC hailed wind energy as an “enabling technology” in the operation of other renewable energy sources, such as green hydrogen. This importance is underscored by projects such as NortH2 off the coast of the Netherlands and, closer to home, an increasing number of proposed “green” hydrogen projects throughout Australia, a number of which are currently subject to feasibility studies - these projects aim to scale the production of “green” hydrogen via the use of wind or solar energy, reducing the dependency on fossil fuels throughout the generation process.

Offshore wind’s quantum leap comes on the back of both a global governmental and private shift towards carbon-neutral economies. Whilst government support has been historically critical in the facilitation of OREI projects, Australia finds itself uniquely positioned to capitalise on both government incentives and, perhaps more crucially, significant private investment.

In this regard, one interesting aspect for Australia is the existence in this country of substantial offshore oil and gas (O&G) assets and the presence of major O&G companies. Offshore wind energy is set to experience a rise to prominence for O&G companies, especially in view of the potential to defer or avoid costly de-commissioning costs as offshore O&G assets reach the end of the production lifecycle and the potential to invest in offshore wind projects as part of an overall net zero emissions strategy. With a developed market for O&G production, both onshore and offshore, as well as one of the world’s leading resources capabilities more generally, Australia is already home to many of the major players in this space. The regulators and stakeholders are well-understood in the market. All of which compliment what, according to BloombergNEF, is a key trend underpinning clean energy investment: the push by O&G companies to build low-carbon portfolios and eventually achieve net-zero emissions. In the past 5 years alone, direct clean energy investment by O&G “majors” has surpassed US$60 billion - with wind taking the lion’s share.

Global developments - the roaring ‘20s and beyond

As the traditional land-owner issues associated with onshore wind projects continue to impact onshore developments, OREI projects open vast areas of the world’s oceans as prime real estate for energy investment - provided, of course, that the anchoring jurisdiction is attractive from both an investment and regulatory perspective. This has been reflected in the countries leading the charge in offshore wind development - each provides a relatively low-risk and stable investment profile (so far as OREI projects go) and in some cases state support in the form of concessions and subsidies, flow-through incentives or even direct funding (such as the UK with its Offshore Wind Growth Partnership and China with various provincial subsidies tied to its goal to reach peak emissions by 2030, followed by carbon neutrality in 2060).

As global and domestic factors including jurisdiction-specific policy-making (and not least a global pandemic) have upset many of the leading OREI markets, Australia’s wealth of natural resources and, for better or worse, its measured approach to the renewables transition has it primed as a force in the future of offshore wind generation. With the UK in the midst of a full-blown fuel crisis and continental Europe struggling to toggle the sharp snap-back of energy demand in the wake of COVID-19 (with its concurrent phase-out of fossil fuels and increasing dependency on renewables), the stage is set for Australia to manage (and regulate) the inevitable expansion of OREI generation and the gradual tapering of fossil fuel production.

Whilst the rapid scalability, opportunity and fertility of resources located in emerging markets such as Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and the Pacific are expected to shape the future of OREI development, it is the UK, Europe and, increasingly, China which are the present titans of OREI design, investment, manufacture and construction.

With that in mind, it is worth canvassing the OREI projects and markets making headlines globally, as well as those on the drawing boards in Australia.

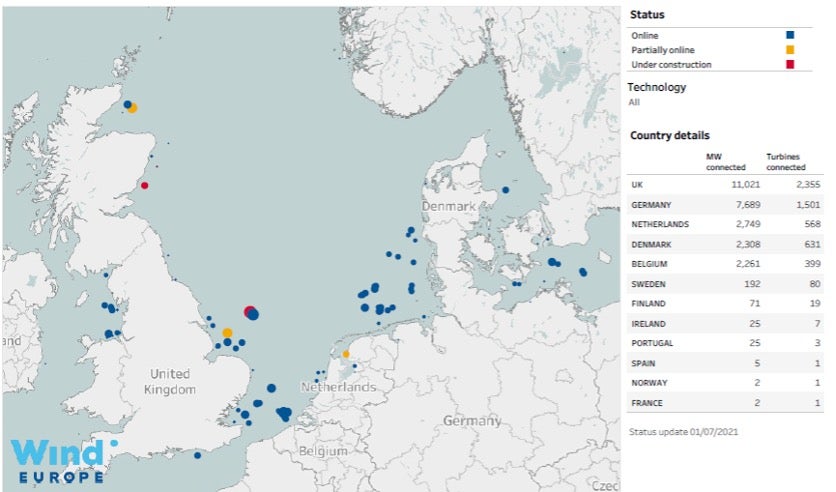

Bounded by the North Sea and its strident blusters, the UK was always going to be a market-leader in offshore wind generation. It is home to almost a third of all offshore wind installations worldwide, and more than any other country, the UK continues to forge ahead with industry-wide governmental support and ambitious installation targets.

Targeting over 40GW of offshore wind production by 2030 (the figure currently sits just north of 10GW), the UK announced the Offshore Wind Sector Deal in 2019, a collaboration and set of guiding principles between both government and industry, and has since stocked an OREI development pipeline that aims to meet, and then exceed, its targets. With offshore wind already powering over 10% of the UK’s electricity needs, energy generated by offshore wind is forecast to be the “backbone” of the UK’s economy by 2030 and support a broader renewables transition through its enabling of “green” hydrogen generation.

Key developments:

Hornsea Offshore Wind Farm : Hornsea One and Two, the two largest offshore wind farms in the world, bring a combined capacity of 2.6GW to the UK grid. Owned by rsted, the landmark projects serve as beacons for the sophistication and scale that a second wind of investment and development can bring to the OREI industry. Hornsea One went operational in 2020, with the second project forecast to reach full production in 2022.

Dogger Bank Wind Farm : A 50/50 joint venture between Norwegian energy company Equinor and Irish renewable energy developer SSE Renewables, the Dogger Bank complex (consisting of 3 construction phases) will be the world’s largest offshore wind farm with a combined generation capacity of 3.6GW (an estimated 5% of the entire UK electricity demand) when completed in 2026.

Kincardine Floating Offshore Windfarm : Located a touch off Scotland’s northeast coast, the Kincardine project is far more important than its relatively meagre 48MW generation capacity would suggest. It is the world’s largest floating offshore windfarm and, according to the American Bureau of Shipping, demonstrates the potential of floating turbines - an asset that is expected to have an increasingly prominent role in the global net-zero economy.

Mainland Europe’s concentrated scattering of almost 6000 turbines across over 120 separate developments highlights the crucial role of environment and geography in harnessing offshore wind capability. Dominated by installations across the North Sea by Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and Belgium (all with ample ocean frontage), and guided by the EU Strategy on Offshore Renewable Energy, which was published in November 2020, offshore wind will be the cornerstone generation asset of a climate-neutral Europe.

With an EU consensus to reach at least 60GW of offshore wind energy generation by 2030, and 300GW by 2050, Europe’s project pipeline underscores the importance of floating turbine infrastructure - a technology that will unlock the deeper waters in the Atlantic, Mediterranean and Black Sea (as it will in Australia) and harness the previously untapped wind resources with utility-scale floating wind developments. To meet these objectives, the EU Commission estimates nearly 800 billion of investment will be needed between now and 2050. Key to this is providing a uniform, clear and supportive legal framework, mobilising private investment and ensuring the stability and dependability of critical port infrastructure.

Key developments:

Gode Wind Farm (Germany) : Acquired by rsted in 2013, the Danish multinational power company pumped 2.2 billion into the project to raise generation capacity to almost 600MW. Lying 45km off the German mainland in the North Sea, a final investment decision on a phase 3 of the project is under consideration.

Borssele 1 & 2 (the Netherlands) : Going operational in 2020 and located approximately 20kms off the coast of Zeeland province in the North Sea, the Borssele wind farm’s 752MW capacity supplies renewable energy equivalent to the annual power consumption of one million Dutch households through its framework of upwards of 90 Siemens Gamesa wind turbines. The Borssele project is the Netherlands’ largest offshore wind farm and connects to the Dutch grid via a purpose-built offshore substation.

Hollandse Kust Zuid (HKZ) (the Netherlands) : With construction commencing in July 2021, Vattenfall’s development of the HKZ windfarm is a turning point for the OREI industry and the commercial production of offshore wind energy. HKZ will be the first offshore wind farm globally to be developed without the use of any governmental subsidies or concessions. Vattenfall’s Netherlands CEO described the project as the start of a “new chapter” and demonstrative of the maturing of the market. The proposition that offshore wind could be cost-competitive with traditional forms of power generation and the more developed clean sources (such as onshore wind and solar) whilst still in its comparative infancy highlights the rapid growth of the industry, as well as the renewable economy’s forecast dependence on it.

Leading the world in new offshore wind installations in each of the last three years with nearly half of the entire global total in 2020, China has forged an offshore wind industry at a frenzied pace.

Propelled by the ambitious targets of reaching peak CO2 emissions by 2030 followed by carbon neutrality in 2060, local provinces and development vehicles have been engaged in a mad scramble for approval and construction with national subsidies for OREI projects set to expire at the end of 2021. Under the scheme, such developments must be commissioned and operational by the end of the year to be eligible. As it stands, China is set to overtake the UK as the largest generator of offshore wind energy by the end of 2021.

Like many other jurisdictions, China is no stranger to the increasingly commonplace pivot of established O&G companies into renewable projects as they drive to retain commercial relevance and viability in what is, in many ways, a new economy. One example is China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), a state-owned oil company, which has earmarked a staggering 4.5 billion yuan (US$700 million) of its annual budget for clean investment. Like others, CNOOC is carefully observing its returns, willing to increase investment and leverage legacy assets, infrastructure and skills should their outlay generate worthwhile returns.

China’s commitment to offshore wind extends into the development and deployment of an increasingly-prominent technology - floating turbines. Typically seen as a solution to unlocking prime wind resources in waters whose immense depth renders fixed-foundation turbines not feasible, China has been pioneering the use of floating turbines in offshore waters near to the coastline. The work has the potential to rapidly advance the development of the technology (potentially reducing costs) and paving the path to the economic capture of offshore wind in waters farther offshore. Advancements in floating turbine technology also have the potential to minimise the impact on marine life (and fishing), visual pollution and established shipping channels and reduce decommissioning costs.

Whether Chinese designed near-shore floating wind turbines lead the charge or play a secondary role, China is set to shape the future of offshore wind, as it has in solar PV. Significant investment by China in the design and manufacture of offshore wind turbine technology will also provide a counterpoint to the traditional global dominance in this field played by a handful of mostly European companies.

Whilst only accounting for a fraction of global offshore wind capacity (42MW as reported in the 2021 GWEC Global Wind Report), the Biden administration has charted a course of advancement for the United States’ offshore wind power industry, setting bold production targets of 30GW of offshore energy (enough to meet the needs of 10 million homes annually and avoid 78 million metric tons of CO2 emissions) by the year 2030. These goals are supported by a series of stimulus measures aimed at promoting and facilitating investment in, and development of, OREI.

The measures are hoped to “catalyse” offshore wind energy and include granting access to US$3 billion in debt capital via the Innovative Energy Loan Guarantee Program (which has already provided over US$1.6 billion in support to onshore developments), partnering with industry (such as rsted) to reap the benefits of public-private R&D and data-sharing, as well as the elimination of existing fossil fuel subsidies.

Vineyard Wind, the United States’ first major offshore wind farm, is the poster child of the Biden administration’s efforts. Sitting just over 20kms from Martha’s Vineyard off Nantucket, Massachusetts, the joint Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Iberdrola (via Avangrid) project is set to produce 400MW and power 400,000 American homes. Having closed a US$2.3 billion debt financing in September 2021, the project demonstrates the growing recognition of offshore wind in the books of traditional financial institutions, with majors such as Bank of America, J.P. Morgan and MUFG Bank on the funding ticket.

Whether or not the United States achieves its offshore wind and broader renewable targets remains to be seen, however one thing is clear - the current administration sees OREI as an asset of the future that must be cultivated and emboldened by directed and substantial state and private-sector support.

Star of The South : Australia’s most advanced offshore wind project, the Star of the South is a proposed A$10 billion, 2.2GW fixed-mast development with plans to connect to the Latrobe Valley, one of the strongest grid connection points in the National Electricity Market. The project plans to capitalise on the extensive existing infrastructure and experience in the region and, at full capacity, would power 1.2 million homes across Victoria - 20% of the state’s energy needs. Majority-funded by Denmark’s Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, Star of the South currently holds a one-off exploration licence from the Australian Government to undertake site investigations off the coast of Gippsland.

Project Gippsland : Floatation Energy, the developer of the world’s largest floating windfarm, Kincardine Offshore Windfarm off Aberdeen in Scotland, proposes to develop a 1500MW project off the Ninety Mile Beach coastline and, like the Star of the South, make use of existing infrastructure by connecting to the Latrobe Valley transmission network.

Victoria Offshore Windfarm Project : Currently in the pre-planning phase and proposed to be located approximately 5.5kms off the coast of Portland, if constructed, the Victoria Offshore Windfarm Project will have a generation capacity of up to 495MW, enough to power more than 330,000 Victorian homes. The project is owned by Australis Energy and is led by an experienced team which has been involved in the development of offshore projects such as the Thanet Wind Farm which, on completion, was the largest in the world.

Oceanex Energy developments : There are currently a number of proposed OREI assets slated for development off the coast of New South Wales, thus far all spearheaded by Melbourne-based Oceanex Energy. The projects are currently undergoing feasibility studies (commenced in May 2021) and envision construction and production in the early 2030s. Each project is of formidable scale, highlighting the anticipated generation capacity of the region:

Novocastrian Offshore Windfarm (2GW, anticipated completion in 2031);

Illawarra Offshore Windfarm (2GW, anticipated completion in 2031);

Eden Offshore Windfarm (2GW, anticipated completion in 2036); and

Ulladulla Offshore Windfarm (1.8GW, anticipated completion in 2033).

Bunbury Offshore Windfarm : One of 5 projects in development by Melbourne-based Oceanex Energy (alongside 4 New South Wales projects), the proposed Bunbury Offshore Windfarm is concurrently undergoing feasibility studies for a 2GW windfarm 50km off the coast of Fremantle. Pending completion of the feasibility study, the project could be operational by 2037.

Cliff Head : Slated as a combined offshore wind and land-based development, the offshore wind farm is proposed to be located in the area centred around the Cliff Head Offshore Oil Production Platform. Jointly owned by ASX listed Triangle Energy (ASX: TEG) and Pilot Energy (ASX: PGY), and with a forecast capacity of 1.1GW, the Cliff Head development is a perfect illustration of traditional O&G producers and assets pivoting to meet the renewable economy and expand into new and replenishing investment streams. By repurposing O&G infrastructure and connections, the Cliff Head OREI and onshore solar development is one to watch with interest, serving as a microcosm of a more universal theme.

WA Offshore Windfarm Project : Owned by offshore energy developer, Australis Energy, the proposed WA Offshore Windfarm is intended to feed into the Western Australia electricity grid within the South West Interconnector System. If constructed, the project will be located approximately 5.5km off the coast, 20kms north of Bunbury, powering up to 200,000 homes with 300MW generation capacity via a framework of up to 37 offshore turbines. The project is currently undergoing assessment by the Western Australia Environmental Protection Authority.

SA Offshore Windfarm Project: Another proposed OREI development by Offshore energy developer Australis Energy, the SA Offshore Windfarm could service the electricity needs of up to 400,000 South Australian homes. The project would be located 10km off the coast of Kingston (230kms south of Adelaide) and generate up to 600MW of offshore wind energy.

Bass Offshore Wind Energy Project : Proposed for installation at either end of the Bass Strait, the stretch of water dividing the island state from mainland Australia (and renowned for its strong and unrelenting winds), the Bass Offshore Windfarm is Brookvale Energy’s proposal to generate up to 2GW of offshore wind electricity and potentially feed into Tasmania’s clean hydrogen and the Bell Bay Advanced Manufacturing Zone - another example of offshore wind’s ability to be a driving force behind other renewable energy sources.

The proposed project complements the Tasmanian Renewable Energy Action Plan which earmarks offshore wind energy as “key” in delivering a fully self-sufficient, fully-green energy supply that can feed into the broader national energy network. Already a national leader on the renewable energy front, Tasmania’s objective is to be a world leader in terms of the production and dependency of renewable energy by 2040.

Australia - Oceans of opportunity

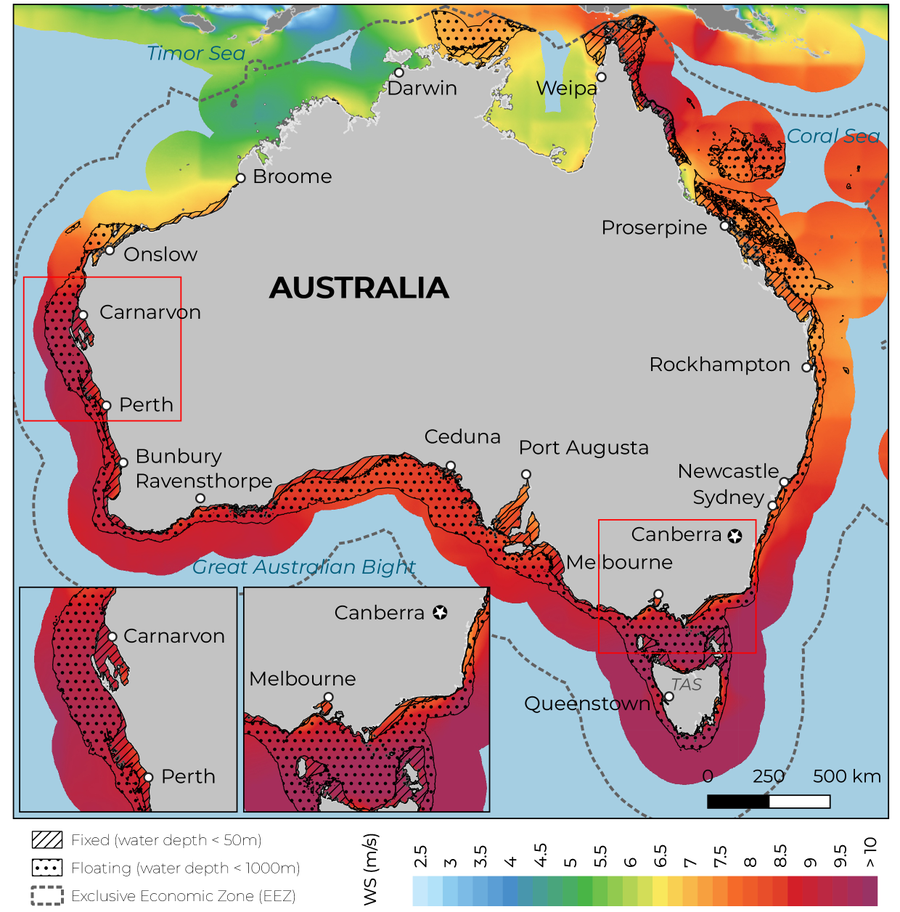

Anyone familiar with Australia’s world-class shorelines can attest to the strength and intensity of its winds. The data backs this up, with a global mapping study published in June 2021 concluding that Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone boasts the 6th largest wind technical resource potential in the world - almost 5000GWs (based on current turbine generator designs).

Whilst the North Sea leads the way as the global figurehead for offshore energy generation, the waters of Australia that most closely compare to that blustery passage linking the UK and Europe present a rich source of potential OREI activity. This is borne out by the curated scattering of Australia’s proposed OREI projects over the eastern seaboard, across the Great Australian Bight and into Western Australia.

Crucially (and unlike many other jurisdictions), the near-shore prime development zones typically lie in grounds familiar to the established O&G industry and within arm’s reach of connection infrastructure, population centres of power demand and both the needed financial and human capital (although Australia faces a shortage of skilled workers in some sectors).

As the gales of the North Sea contend with uncharacteristic timidity, Australia’s offshore wind developments (both proposed and future) offer the opportunity for Australia to become a global offshore wind superpower especially if such projects underpin an Australian “green” hydrogen export industry. This opportunity will also be driven by the early closure of coal fired power plants on the eastern seaboard of Australia and the continuing transition to renewable energy sources across Australia.

The Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Bill 2021

Until now, many commentators had expressed concern that Australia was dragging its feet in the global race to a renewable economy, with as many as 12 potential offshore wind projects in some stage of development. In fairness, this is only part of the story - until relatively recently, Australia’s deep coastal waters and strong wind resource has meant that established offshore wind technology was probably not fit for purpose. However, given the advancements in large scale wind turbine capacity factors and floating turbine and cabling designs, that is no longer the case and Australia urgently needs a regulatory framework that encourages investment in OREI. The Bill hopefully paves the way for the development of these projects and many more, headlined by the 2,200MW Star of the South offshore wind project off the coast of Gippsland in Victoria, and the Sun Cable project which aims to connect Singapore with Australia’s abundant solar resources via more than 4,000km of high-voltage underground cables.

Whilst the devil, as always, will be in the detail and we are yet to see what the Bill’s licensing regime will look like in practical application, it promises fertile ground for future investment in the sector and primes Australia to become a leader in the net-zero energy transition.

Following the closing of submissions on 15 September 2021, the Bill was subject to inquiry and report (discussed below) by the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee. There, the Bill was met with bipartisan support and its passage was recommended. The Bill is scheduled for further parliamentary debate on 21 October 2021, after which a clearer view of the regime - and the future of OREI developments in Australia - will emerge.

The Bill introduces Australia’s first licensing regime for OREI projects. Presently, OREI proponents have no defined approval and development pathway or protections - the absence of these matters has contributed to a reticence to invest in offshore electricity infrastructure. This in turn has had a broader flow-through impact on the Australian economy in terms of the opportunity costs of a less-diverse energy mix and the underdevelopment of a specialist OREI workforce and management expertise. Ultimately, project sponsors, utilities, off-takers and financiers require certainty - they need a predictable and stable permitting and regulatory regime that facilitates investment. Lack of regulation as much as over-regulation creates commercial uncertainty and risk - in Australia lack of regulation has hindered the development of OREI projects while funds have flowed freely into the North Sea and China for almost a decade.

The Bill aims to address this and strike the requisite balance, by creating a clear and secure environment for investment in, and development of, OREI projects. The Bill defers much of the detail to the regulations. Importantly, specifics around the exact application process, the financial security requirements and contents of the management plans (discussed below) are yet to be provided. Once passed, the Bill will be administered by the National Offshore Petroleum Titles Administrator as “Registrar” (NOPTA) and the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environment Management Authority as “Regulator” (NOPSEMA).

Investors in the OREI industry will be monitoring the passage of the Bill and the subsequent regulations with interest as the licensing regime is set to become the new regulatory OREI threshold. Given the likely transferability of late life offshore petroleum infrastructure to OREI projects and the opportunity to defer (or reduce) the cost of the decommissioning of that infrastructure, O&G companies will also be watching with interest - interestingly, such companies are likely to have existing relationships with both NOPTA and NOPSEMA, as these bodies are the traditional offshore O&G regulators. Such asset recycling is also to be encouraged given that it would allow OREI to take advantage of known environmental data for a particular site and minimise the differential impact on the marine environment of new projects. Redeploying existing O&G assets would also represent a significant reduction in the overall cost of a new OREI project, and therefore the levelized cost of the electricity it produces, as well as reducing the construction risk of a project and the safety risks to workers.

Snapshot of the licensing regime

The base prohibition and licensing requirement

The Bill prohibits all activities relating to OREI projects unless that activity is licenced.

Geographical coverage? | 3 to 200 nautical miles from Australia’s shore (Australia’s exclusive economic zone). | |

What infrastructure is covered? | Any infrastructure that has one of the following as its primary purpose:

This includes both fixed and tethered infrastructure. | |

What activities are prohibited? | Constructing, installing, commissioning, operating, maintaining, or decommissioning the infrastructure. | |

What is renewable energy source? | A “Renewable energy source” is defined broadly. It includes wind, tides, solar, geothermal etc., and can be extended further by regulation. |

The parameters of the prohibition are as follows:

Unlicensed activity that contravenes this prohibition risks a monetary penalty and up to 5 years imprisonment for any person involved.

Declared areas

Before a licence can be granted, an area must first be declared appropriate for OREI.

This process includes a 60-day consultation period in which the Minister is required to consider any submissions made by the public, as well as consultation with the Defence Minister and the Minister responsible for the Navigation Act 2012 (Cth). Once the Minister is satisfied that the area is suitable for OREI, the Minister may “declare” an area indefinitely or for a limited period. Declarations can also be conditional - for example, specifying the types of licences available in that area, or even imposing conditions on all licences granted in respect of that area).

A declaration in relation to an area can be modified or revoked - but the Minister will need to undergo a similar consultation process to do so. A declared area does not need to be contiguous and the Bill does not specify a minimum or maximum requirement in regard to the size of such an area.

Licence types

While much of the specifics will be provided for in the regulations, an overview of the different licence types is set out below:

| Commercial | Research | Transmission | ||

| Feasibility licence | Commercial licence | Research and demonstration licence | Transmission and infrastructure licence | |

| Obtaining a licence | By application The Minister can also invite parties to apply | By application | By application | By application |

| Purpose | A temporary licence for holders to then apply for the commercial licence | A licence for commercial OREI activities | A licence for small-scale OREI projects to research / demonstrate emerging technologies | A licence to store, transmit or convey energy to onshore users |

| Maximum duration (with potential for extensions) | 7 years | 40 years | 10 years | Intended to be for the life of the asset |

| Key pre-requisites (or “merit criteria”) | The applicant has, or is likely to have, the technical and financial capability to carry out the proposed project, and the project is likely to be viable | The applicant holds a feasibility licence The applicant has a management plan approved by NOPSEMA The project is substantially similar to the project proposed under the feasibility licence. | The licenced area may overlap with another licence already granted. If so, the Minister must be satisfied that the proposed activity does not interfere with the other licence holder(s) in the area. | The licenced area may overlap with another licence already granted. If so, the Minister must be satisfied that the proposed activity does not interfere with the other licence holder(s) in the area. |

In addition to the pre-requisites described above, the Bill also imposes general requirements applying to all licence types, including that the proposed licence will need to be in respect of a declared area and must be consistent with any conditions applying to that declared area. Additional criteria may be specified in the regulations.

The Bill’s Explanatory Memorandum also notes that these licenses only operate in relation to the Commonwealth offshore area and additional state or territory licences (and development approvals) may be required for connection to onshore energy infrastructure.

Applying for a commercial licence

The application process for feasibility and commercial licences is expected to be more competitive than that for research or transmission licences. In relation to feasibility licences, the Bill provides that:

other than directly applying for a feasibility licence, the Minister can also invite applications; and

the Minister may invite “financial offers” at its discretion.

As above, the Bill lacks details and defers to the regulations for the specific application process. The Explanatory Memorandum describes that these provisions may be used in situations where multiple applications of similar merit have been submitted - in this case the Minister can invite financial offers as a “tool” in deciding which applicant is successful. As the Bill continues to be considered in Parliament, this could remain a discretionary tool for the Minister, or may take the shape of a more formal tender process. At this point, the generality of the drafting leaves open what the final process could look like.

After obtaining a licence

After a licence has been obtained, and before OREI activities can commence, two further requirements must be satisfied:

Developing a management plan : Licence holders will need to have a management plan approved by NOPSEMA. Among other things, this management plan must cover environmental management, maintenance of the OREI as well as how the holder will ensure compliance with its financial security obligations (see below). The regulations can also extend content requirements to include work health and safety, emergency management, monitoring, auditing and other matters.

Providing financial security : Licence holders must at all times provide the Commonwealth with sufficient financial security to pay for decommissioning of the OREI, removal of equipment and remediation of the area. The Bill does not detail the form or quantum of this financial security. However, the Explanatory Memorandum states that the timing and amount required will be assessed and approved by NOPSEMA on a case-by-case basis. This was a key item in respect of which the Committee received many submissions and features in the Committee’s Report.

Other points to note

Levy : Licence holders will be required to pay a levy, which will be established in the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure (Regulatory Levies) Bill 2021 currently also being considered by Parliament.

Non-interference : The Bill creates a strict liability offence for licence holders who interfere with other lawful users of the area in a way that is “greater than is necessary” for the exercise of their licence rights. This includes interfering with fishing operations, marine conservation and native title rights in the area. This offence poses interesting questions in relation to matters such as noise, visual aesthetics and other features of the OREI and how those impact the OREI’s surroundings.

Change of control and transfers : Not unexpectedly, there are change of control and transfer restrictions under the licences. These actions will require prior approval by the NOPTA, which will depend primarily on whether the resulting licence holder will still be capable of complying with the licence conditions. (Such restrictions were the subject of numerous responses to the Committee.)

Other environmental requirements : The licensing regime under the Bill does not replace or supersede any environmental legislation and existing environmental permit or approval requirements - these will still need to be obtained alongside any OREI licence. Importantly, the Bill does not clarify or streamline parallel Commonwealth and state level environmental approval pathways applicable to OREI as it connects to the onshore NEM.

Operations and safety : In view of the security and logistical issues of operating offshore sites, the Bill also requires compliance with various safety regimes, including the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (Cth) (WHS Act ) (with some modifications) when on OREI, and various maritime regimes when in transit to them. It also creates safety and protection zones around offshore infrastructure which prohibit certain activities from being undertaken in that area. It is noteworthy that the Bill has adopted (and adapted) the WHS Act as the safety regime to be applicable to OREI, given that the O&G industry has a bespoke regime.

NOPSEMA enforcement powers : The Bill provides NOPSEMA with wide powers relating to compliance and enforcement, including issuing fines, directions and seeking prosecutions to ensure license holders comply with licence conditions, regulations and workplace health and safety rules.

Interaction with other legislation

The Bill makes express provision for the application of state and territory legislation to Commonwealth offshore areas. However, the Bill also provides for the displacement of state and territory laws by the regulations. This has caused some disquiet among stakeholders, primarily state governments seeking a prescribed framework for consultation prior to the overriding of their legislation and also market operators concerned with the possibility of shifting goalposts and the challenge of meeting multiple (and potentially inconsistent) regulatory requirements.

Confining the displacement power to the regulations is justified in the Explanatory Memorandum as providing a suitably flexible and efficient way of identifying and tailoring the application of laws to the particular OREI and its related operations. The mechanism is intended to assist in allowing applicable existing laws to flex around the OEI industry as it develops. It can also be deployed in circumstances where a state or territory law may be appropriately applied to an activity that occurs onshore, but that may lead to an inappropriate or result were it to be imposed on projects and persons operating offshore. Whilst this approach broadly mimics that employed by the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 , it remains to be seen how the OREI regulations will interact with existing laws.

There are a number of existing laws that will continue to feature prominently and be applied by the Bill. As indicated above, the WHS Act will apply to operations on the OREI (as will certain other offshore maritime safety regulations when in transport). Moreover, Australia’s primary piece of environmental legislation, the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) will feature prominently and need to be addressed. Crucially, environmental approval for each OREI project will need to be sought and obtained under the EPBC Act and under each applicable state-level environment and planning instruments.

It is interesting to examine the regulatory position in the United Kingdom by way of comparison. Whilst OREI in the United Kingdom requires consent under either the Planning Act 2008 (UK) or the Electricity Act 1989 (UK) -OREI in Australia requires both planning and electricity approvals as well as environmental approvals at Commonwealth, State and local government levels.

In the UK, OREI with more than 100MW capacity is classed as “Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects” or “NSIP”. This classification attracts the requirement to obtain a Development Consent Order (which in turn attracts other associated requirements). Notably, an environmental impact assessment is required for large OREI in the UK. This involves an assessment of all potential environmental impacts of the OREI and brings in a public consultation process.

It will be interesting to see if Australian legislation, especially the regulations made to implement the Bill, follows in the UK’s footsteps to distinguish between large and small OREI projects. Doing so could reduce barriers to entry for sub-utility grade OREI, promote smaller offshore developments and create a market for private wind infrastructure (not dissimilar to solar PV and onshore wind).

An opportunity for O&G - late life assets and beyond

Offshore O&G companies may be looking to the Bill with interest in the context of what it could mean for decommissioning of late life offshore O&G infrastructure. For example, existing offshore infrastructure could become the foundations for new OREI projects and this may delay and/or reduce decommissioning liabilities as well as streamlining environmental approvals for OREI. Given the quantum of decommissioning liabilities for some offshore O&G assets, regulators may look to O&G companies to remain involved. In addition, participating in an OREI project may have the added benefit of bolstering a company’s increasingly important ESG credentials.

This has become a familiar occurrence in the more developed OREI markets overseas. As governments mandate clean energy targets and push for carbon-neutrality in the not-too-distant future, established O&G companies can be certain of two things - one, that they need to take targeted action to reduce emissions from established O&G operations and two, that future profits lie elsewhere.

In what is a comparable engineering proposition (developing large-scale infrastructure in the middle of the ocean), O&G companies are the unlikely candidates to be best equipped to manage the transition and become leaders in the OREI industry. Notable examples include BP’s recent bid to develop two wind farms in the Irish Sea, Norway’s largest petroleum company, Equinor, which has marked itself as a leader in floating wind, as well as fellow majors Shell, Total and Chevron which have all earmarked offshore wind for prominence in their portfolios.

The response - what does the market say?

Speaking at the group’s 2021 Green Energy Conference, Macquarie Group Limited CEO, Shemara Wikramanayake, echoed the sentiments of many in declaring that governments must now prioritise renewables in their energy mix and “remove the bottlenecks that hold up project development”. Wikramanayake underscored the importance of governments connecting their renewable ambitions with “plans, policies and support mechanisms”.

Perhaps it is symptomatic of Australia’s laboured awakening to the potential of OREI that the CEO of the world’s largest infrastructure asset manager thought it apt to point out that, “with the right market environment, the private sector will invest, bringing the scale and innovation that drives down costs”. Until the Bill, Australia’s regulation of the OREI industry was piecemeal and decentralised - this has led to a “market environment” that has not spurred investment, but rather left multi-billion-dollar developments becalmed.

Overall, the Bill has been met with reserved optimism. Whilst there still remains a level of uncertainty - and eagerness to see the detail - the Bill is perceived as an important step in supporting the transition towards a renewable economy and a critical first step in unlocking the wealth of global investment and R&D in the offshore renewables sector.

Legal issue and challenges for OREI Investors

Environmental & Fisheries Management

A common thread among OREI projects the world over is the potential impact on marine life, as well as on the fishing industry.

One matter of potential concern is the exclusion zones that will be applicable to licensed OREI. The fishing industry typically pushes for sub-100m exclusion zones and predicates this on the fact that much of the fisheries’ resources reside under or close to the artificial infrastructure. In the United States, the development of Vineyard Wind, the country’s first major offshore wind farm, has been hounded by similar issues, even being brought before the Court of Appeals by a fishing group alleging that the projects added “unacceptable risk” to the safety of fishermen and their vessels. However, the Senate Report describes how positive the fishing industry is about OREI in its submissions and that they see artificial reefs as being potential benefits to the fishing industry - so it seems this will be not so much an issue as a matter of striking the right balance.

Others have raised concerns regarding the impact on marine life and conservation more broadly, with conservation groups seeking clarity on the Minister’s consideration and consultation process, and whether the marine and environmental impacts will be adequately assessed for the purposes of a declaration. It has been mooted that consultation with the Minister administering the EPBC Act should be a feature of the zone declaration process rather done on a piecemeal, project by project basis.

The willingness of state environmental agencies to work in a constructive manner with OREI developers (and likewise, the willingness of Commonwealth agencies to work with state agencies) to allow projects to proceed without undue delay or onerous conditions will also be important. If OREI development are to be accelerated, ‘red tape’ will need to be minimised and state environmental and planning laws may need to be amended to create the necessary flexibility for addressing OREI projects. The basic framework is already in place with each State having special planning pathways available to major or significant development projects and the Commonwealth having a major projects bureau to assist major developments to cut through red tape.

Regulatory regimes

As noted above even once an OREI licence has been obtained under the Bill, it will still be necessary to navigate the energy regulatory regime applicable in the local jurisdiction - this will include obtaining the appropriate generation licence(s) from state authorities and NEM registration from AEMO for the development and operation of the OREI, securing grid connection and assessing and managing associated issues such as grid constraints and MLFs. Associated battery storage also may be required for certain projects so that energy can be stored (onshore or offshore) until required as a mitigant against grid connection issues, so it will be necessary for the Bill and importantly its regulations to be applied appropriately to storage assets.

Similarly, as the Australian OREI industry develops and multiple OREI projects are located within the same or adjacent declaration zones, the transmission arrangements between projects will need to be fairly and transparently regulated. Such inter-project connections could potentially open up much larger and further offshore wind resources as each successive OREI project could piggy-back on the then existing transmission infrastructure, provided the regulatory and liability regimes were conducive to doing so.

Given the scale of expenditure required for OREI, investors may also want to see more robust and dedicated onshore connection and transmission arrangements which may drive a need for further expenditure to replace ageing transmission and distribution assets in locations close to offshore energy projects or the development of new transmission connections in those areas. Another issue that will need to be addressed is how MLFs will be applied in the case of OREI so as not to materially disadvantage the new offshore wind projects and existing onshore projects.

Investors in electricity infrastructure will also need to become used to working with NOPTA and NOPSEMA and, when utilising offshore O&G infrastructure, understand the offshore O&G regulatory regime particularly in relation to decommissioning and trailing liabilities, indeed even existing O&G investors will need to adjust to NOPSEMA’s functions in respect of OREI being different to its functions in respect of O&G.

Financing and the role of government “green” banks

Given offshore wind is a clean technology, financial support should be available from ARENA in the form of grant funding and CEFC in terms of loan finance for some projects, at least in respect of feasibility studies and the early stages of permitting.

With a growing list of overseas OREI projects as precedents and with OREI technology becoming increasingly established, lenders are increasingly willing to provide project financing to OREI projects and even to take construction risk. Finance for Australian offshore wind projects should be available from the private sector, domestically and internationally. In this regard, international banks which have had experience financing offshore wind projects in other countries will have an important role to play in bringing their capital and expertise to the Australian market and stepping up to play a lead role particularly with those international sponsors that have a successful track record in offshore wind in other markets.

Other sources of funding such as export credit agencies have a critical role to play in financing the development of offshore wind assets as they have to date in financing large scale LNG projects in Australia. Australia’s major export partners (especially Japan, Korea and China) have announced policies in support of offshore wind and renewable hydrogen and their export credit agencies should therefore be able to provide support to their nation’s manufacturing and trading companies involved in appropriate Australian OREI projects.

It will also be interesting to see whether state governments in Australia have any appetite to assist in the development of offshore wind projects particularly in respect of the funding of any new or upgraded transmission infrastructure required or associated infrastructure such as batteries, required for a project to be bankable.

What’s next?

Following its introduction, the Bill was referred to the Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee for inquiry and report. The Committee’s report was delivered on 14 October 2021 and recommended the passage of the Bill, despite the lack of detail (such was the fervour of its support). The Committee's report noted that while there had been broad support shown for the Bill from interested stakeholders, some key issues had been raised by stakeholders. These broadly fell into the following categories or themes:

State governments wanted to see greater co-ordination of consultation between Commonwealth agencies and state authorities on the declaration of OREI zones and on particular project approvals.

Many stakeholders recommended that there be a requirement for extensive environmental impact consideration at the Ministerial level before a particular zone was declared, rather than leaving it to individual projects to drive the impact assessment for their specific project within a zone, which may result in project sponsors expending significant resources on environmental studies to no avail.

The change in control restrictions were seen by some investor parties as likely to have an adverse impact on the how infrastructure and superannuation funds could invest in OREI for the long term and therefore may limit their initial involvement.

Reviewing the detail of the regulations was a key component to assessing the Bill.

A number of stakeholders commented that the timing and sizing of the required financial security (or decommissioning bond) should be carefully considered by regulators, including a proposal that the quantum of a financial security given for a project ramps up over time and is therefore funded by project revenue rather than locking up significant equity during early years.

There still remains the need for projects to navigate the parallel and sometimes contradictory Commonwealth and State environmental and planning approval regimes.

The Bill’s final form is not likely to be available for some time, with the regulations (which are to implement significant parts of the OREI operational framework) not expected to be complete until well into 2022. This lead time reflects the task ahead for the legislators and regulators: to develop a regulatory framework that is well-crafted from the outset appropriate for the complexity and sophistication of the global OREI market.

Stakeholders, principally sponsors and financiers, should take this time to acquaint themselves with the Bill, given the committee has flagged its intention to consult widely with a view to presenting a framework that creates industry certainty, sufficient lead time for complex project design and financing, and workforce delivery.

G+T will continue to monitor the Bill and the development of the OREI industry in Australia.

The authors would like to acknowledge Christian Smolders’ contribution in the research and preparation of this Article.