In our previous snapshot article ‘Unlocking potential: the role of institutional capital in social and affordable housing’ we outlined ways Community Housing Providers (CHPs) source and structure funding required to develop, build and operate social and affordable housing (SAH).

In this article, we explore why a special purpose vehicle (SPV) is a popular model for SAH projects and highlight some of the unique challenges an SPV and its parent CHP can face in project development and delivery – both at a commercial and regulatory level.

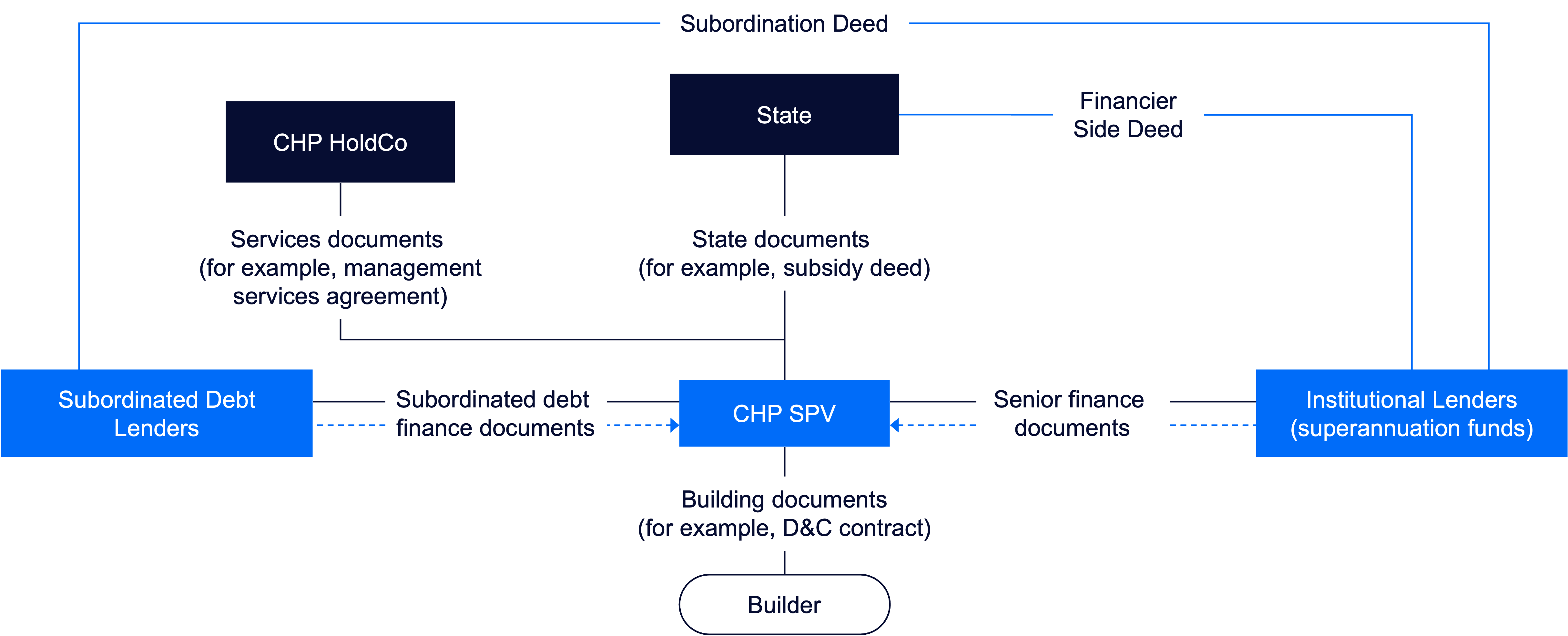

To set the context, below is a diagram of an SPV project structure, outlining the role played by each party, document and relationship within a typical SAH funding scenario.

Why are CHPs becoming larger and more complex?

CHPs were traditionally a single corporate entity operating as a not-for-profit company (and often as a registered charity). Many CHPs held housing assets and ran operations all within the same entity (or perhaps with a single subsidiary). They did not need to consider the use of an SPV entity, mostly because the SPV structure was unnecessary to their requirements.

As public and private funding into SAH projects has increased in recent years with the strong push by government to build out the sector, new public-private funding models for building and operating SAH projects have been introduced at the federal and state levels. As the funding arrangements and the requirements of those providing the funds have become more complicated, CHPs have discovered the benefits of adopting an SPV structure.

SPVs in the not-for-profit world are now favoured for many of the same reasons as SPVs are favoured in the for-profit world. These include:

To isolate and quarantine project risk to the SPV company.

To ensure any security for the project debt is limited to the SPV entity and its assets so that the debt is not cross-collateralised using assets from other SAH projects.

To make the exit (whether by way of a refinance or sale of a SAH project) far easier and faster through a sale of the SPV’s assets as a ‘package’.

In addition, the SPV structure gives a CHP more flexibility in its contracting arrangements. The CHP can use the SPV as the vehicle through which it contracts with financiers, government and builders, while other operating entities within the CHP group might contract with other project stakeholders such as tenancy and asset managers. This helps with clarifying each party’s roles and responsibilities and with managing risk.

From a ‘nice to have’ to a ‘have to have’

Growth in the SAH sector has accelerated rapidly in the past two years, in large part due to recent government initiatives requiring (or at least strongly encouraging) the use of an SPV structure to ring fence projects. For example, the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) – a $10 billion fund for social and affordable housing – and the National Housing Accord both specify that a private developer or investor must partner with either a registered CHP or other eligible not-for-profit such as an Indigenous or veterans’ housing entity to apply for HAFF backed project funding. SPVs are eligible for this funding provided that at least one of its members is also eligible and meaningfully participates in the governance and operations of the SPV.

Several states have adopted similar programs which require CHPs to establish an SPV structure, such as under the Victorian Government’s Ground Lease Model (GLM), where the State enters a long-term lease of public land with a not-for-profit CHP SPV (to ring fence the project). The SPV is then responsible for the financing, building and operation of the SAH project.

With the rising use of SPVs in the sector, the federal and state governments are starting to introduce regulatory reform to streamline the registration process. For example, in mid-2024, the New South Wales Registrar issued a paper entitled ‘Guidelines for Streamlined Registration of a Special Purpose Vehicle’, which recommended the State introduce a streamlined registration process to, among many other benefits, reduce the regulatory burden on CHPs aiming to access the HAFF and reduce registration delays. Under these proposed guidelines, the SPV will need to meet specific criteria such as having a member registered as a CHP (or be wholly owned by a CHP) and being (or having applied to be) a registered charity, but subject to these requirements the registration process should become quicker and easier.

These trends all point in one direction – the growing and continued use of SPV structures in the SAH space.

The unique challenges of an SPV structure for SAH projects

As CHPs have adopted the SPV structure for funding projects, they have also been forced to contend with additional regulatory obligations arising from the use of an SPV in this context. These include:

The need to carefully select board members that are appointed to the SPV, to ensure the right number and mix of knowledge, ability and interest – for example, the board may include both a CHP representative and nominees of institutional capital funders, each of whom may have competing interests and risk tolerances.

The potential for reputational risk for a CHP – while the SPV structure is helpful in reducing asset risk to the broader CHP group, a poorly managed SAH project can still result in reputational damage to the CHP and the CHP may still find itself ultimately accountable, especially if it has guaranteed the obligations of the SPV.

That CHP SPVs typically need to be registered charities, which brings with it the additional regulatory burden of complying with charity laws (especially reporting requirements).

Complexities in satisfying Australian Taxation Office requirements as they relate to the CHP’s (and the SPV’s) ability to access charity tax concessions (such as income tax exemption, fringe benefit tax concessions, GST concessions and deductible gift recipient endorsement).

The specific requirements for state-based tax concessions (namely stamp duty exemption and land tax exemption).

Any conditions imposed by Housing Australia or any other contributing government or funder.

As a result, the SPV funding structure so familiar in the for-profit sector can, and must, be used in a more considered and organic way in the SAH sector, to address the needs for all interested parties, to manage group governance, conflicts of interest, board composition, delegated authorities, the need for transparent reporting of related party transactions and reserved matter regimes (particularly relating to institutional capital providers).

We may also see the emergence of a three-tier structure with a ‘HeadCo’, ‘MidCo’ and SPV – where MidCo might be set up as a State-based entity with its own SPVs (potentially to assist in different funding structures or to combat the sometimes competing regulatory obligations imposed by Community Housing Registrars in different jurisdictions).

Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission – a focus on complex structures

To further add to the complex environment for SPVs, regulators are alive to the risks of complex structures in the not-for-profit sector, including those used to fund SAH projects. The Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission (the ACNC) published guidance in March 2024 that said (in part):

The ACNC is becoming increasingly concerned about the use of complex structures that may be part of attempts to conceal non-compliance with the ACNC Act and Regulations… Our enforcement and compliance activities will be targeting charities that attempt to conceal non-compliance with the ACNC Act and Regulations by deliberately using complex structures to avoid adherence to the laws we administer. We will also continue to refer matters to other appropriate government agencies where we have concerns about suspected breaches of relevant law.

CHPs need to be across the risks these structures pose and ensure they carefully consider the best possible structure for their projects, obtain the necessary legal and tax advice and mitigating risk.

Acting with purpose when building for a purpose

What does this all mean for CHPs? It means building a structure intentionally (with an eye for the future) is essential.

Any SPV structure must be fit for purpose and ensure compliance with regulatory and governance frameworks. If used in the right way, SPVs can greatly benefit a CHP and allow it to operate in a more sophisticated way, which in turn will benefit the sector as a whole and ensure the continued growth of social and affordable dwellings for those who need them most.

Gilbert + Tobin is here to help CHPs, their investors and debt funders – we have dealt with all the major issues an SPV will face – from regulation to governance and financing – and can help you design the most efficient structure. Please feel free to reach out to our key contracts below.