In the 2020-21 Federal Budget handed down on 6 October, the Government revealed its plan for Australia’s economic recovery from the coronavirus, embarking on an unprecedented campaign of expenditure that will see Australia’s debt levels rise to almost $1 trillion.

The clear and immediate priority of the Government is to reduce the unemployment rate to below 6% by 2023. In line with this objective, a key element of the government’s stimulus package is additional investment in infrastructure because of its potential to create jobs during construction and the need for ongoing operation and maintenance.

The infrastructure initiatives announced in the Budget are part of the Government’s five‑year JobMaker Plan, which forecasts expenditure of $74 billion and is focused on driving sustainable, private sector‑led growth and job creation. The initiatives include:

- an increase in the Government’s infrastructure investment pipeline by $10 billion to $110 billion over ten years; and

- temporary investment tax incentives worth $26.7 billion for temporary full expensing and $4.9 billion for temporary loss carry‑back, and by improving the ease of doing business by reducing regulatory burdens. These incentives are not confined to infrastructure investment.

More detail on the proposed projects can be found in the alert we issued on 6 October 2020 ('Australian Federal Budget 2020-21: The Infrastructure Package').

In light of Government’s immediate imperative to create jobs, the focus is on road and rail projects which are ‘shovel ready’ and can theoretically commence within the next six months. This seems to be the reason for the lack of any social infrastructure initiatives despite many commentators pointing out that investment in affordable housing would tackle unemployment and homelessness.

In this article, we explore the key taxation measures announced in the Budget, in particular temporary full expensing, and what they may mean for future investment in infrastructure.

Temporary full expensing

This measure allows entities which satisfy specified criteria to deduct the full cost of eligible depreciating assets that are first held, and first used or installed ready for use for a taxable purpose, between 6 October 2020 (2020 Budget Time) and 30 June 2022. Businesses are also able to deduct the full cost of improvements to existing eligible depreciating assets made during this period.

The policy underpinning temporary full expensing is to support businesses that invest by significantly reducing the after-tax cost of eligible assets. Temporary full expensing also creates a strong incentive for businesses to bring forward investments that were initially planned for a later date.

To be eligible for the temporary full expensing measure:

- the entity must carry on a business;

- the business must have an 'aggregated turnover' of less than $5 billion for an income year (“Turnover Threshold”);

- the asset must be a depreciating asset;

- the depreciating asset must be first held, and first used or installed ready for use for a taxable purpose, between the 2020 Budget Time and 30 June 2022; and

- the depreciating asset must be located in Australia and principally used in Australia for the principal purpose of carrying on a business.

Our initial observations on this measure in the context of infrastructure investments are set out below.

Depreciating assets vs capital works

The rules permitting tax deductions for depreciating assets over their effective lives do not apply to ‘capital works’. Depreciating assets are defined as assets which can reasonably be expected to decline in value over the time that they are used. Capital works are defined to include ‘structural improvements’ such as sealed roads, lined road tunnels, or earthworks such as embankments, culverts and tunnels associated with a road or railway.

Given that the infrastructure initiatives announced in the Budget were for road and rail projects, the temporary full expensing measure will not be available in respect of expenditure on the construction of assets to the extent they are capital works. However, some assets involved in a road or rail project may be depreciating assets and, therefore, potentially fall within the rules. For example, ATO guidance identifies various transport related assets as eligible for depreciation deductions including:

- electronic toll collection assets such as digital measuring instruments, transponders, and optical character recognition cameras;

- electrification assets such as overhead distribution lines, power transformers and substations;

- communication, computer and passenger support assets such as CCTV systems, control systems, ticketing machines, passenger information displays and radio base stations;

- signalling assets; and

- freight or passenger trackwork.

The distinction between depreciating assets and capital works is important because the cost of constructing capital works is generally only deductible on a straight-line basis at a rate of 2.5% per annum, which equates to an effective life of 40 years. The ability to immediately expense the cost of depreciating assets when they are first used or installed ready is potentially significant as it may defer the time at which revenue from an infrastructure project becomes subject to Australian income tax. For example, some depreciating assets used for transport services have long effective lives (e.g. electricity distribution lines have an effective life of 33⅓ years and passenger trackwork has an effective life of 40 years) – the ability to immediately expense these assets rather than depreciate them over their effective lives can be of significant value.

Capitalised labour

The ATO has expressed the view that salary and wages and related labour on-costs of employees who are engaged in the construction of capital assets must be capitalised into the cost of such assets for tax purposes. These costs would ordinarily be deducted for tax purposes over the effective life of the relevant capital asset. However, the temporary full expensing measure may allow such costs to be immediately expensed rather than amortised over the effective life of the asset.

Holder of the asset

The entitlement to claim tax depreciation rests with the ‘holder’ of an asset. The holder of an asset for tax depreciation purposes is not necessarily the legal owner and can be influenced by factors such as whether the asset is fixed to land or is the subject of a lease.

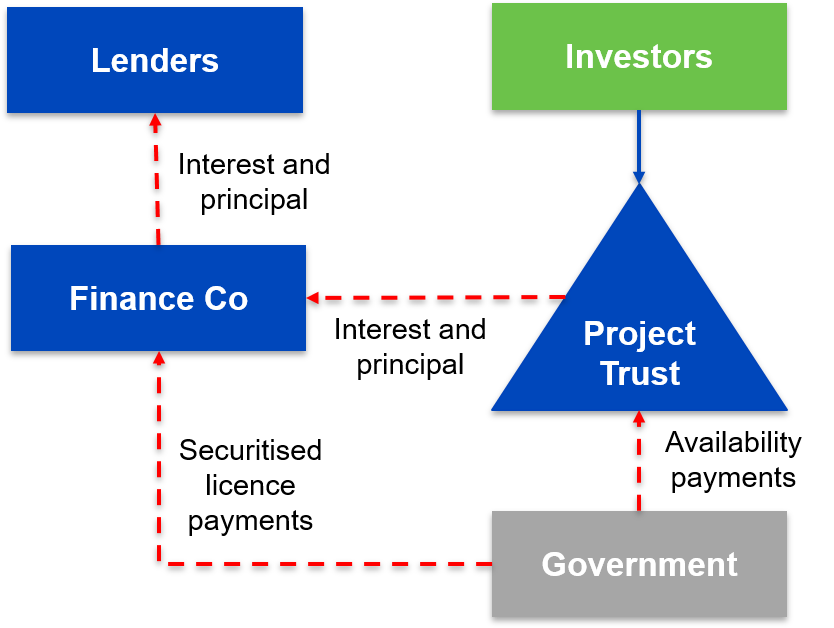

This approach is relevant in the context of some PPPs for example. The ATO has previously issued guidance on the construction of social infrastructure under a PPP model using a securitised licence structure. Under this model, a private sector consortium finances, designs, constructs and maintains certain social infrastructure, and the government obtains title and makes payments to the consortium over a period for the cost of the infrastructure, its ongoing maintenance plus interest on debt and return on equity. Examples of the type of infrastructure covered by the guidance include schools, hospitals, prisons, roads and public utilities. One advantage of a securitised licence structure in a PPP project is that the Project Trust is not entitled to claim depreciation deductions and, therefore, does not encounter the practical difficulties of applying Division 250 (discussed below). A typical structure is depicted below:

Under this PPP model, on completion of the design and construction phase, the government owns the relevant asset and the consortium is granted a licence to carry out ongoing maintenance activities. Accordingly, the Project Trust is not entitled to claim depreciation deductions in respect of the relevant asset as it is not the holder of the asset for tax purposes.

The key takeaway is that depending on the nature and structure of the relevant infrastructure project, therefore, there may be no entitlement to depreciation deductions in which case the temporary full expensing measure will be of no benefit.

Second hand assets

The temporary full expensing measure will not be available where an infrastructure asset is owned by the government and subsequently transferred to a private sector entity. This exclusion to the availability of the temporary full expensing measure applies where another entity (including a government) held the asset when it was first used, or first installed ready for use, other than as trading stock or merely for the purposes of reasonable testing or trialling.

Division 250

Where an entity holds an asset for the purposes of the tax depreciation rules, capital allowance deductions will not be available where the depreciating asset is used, or its use is controlled, by a tax exempt entity such as a government entity, and the private sector entity has an insufficient economic interest in the asset. In such cases, the arrangement under which the government uses the asset is treated as a deemed loan and the private sector entity will be required to pay tax on a return worked out on a compounding accruals basis. In these circumstances, the benefit of an immediate deduction for the cost of a depreciating asset under temporary full expensing will not be available.

Aggregated turnover threshold

When determining an entity’s aggregated turnover for the purposes of the Turnover Threshold, it is important to note that the turnover of related parties may be taken into account. More specifically, aggregated turnover is the sum of an entity’s (the Test Entity) ‘annual turnover’, the annual turnover of entities ‘connected with’ the Test Entity and the annual turnover of ‘affiliates’ of the Test Entity. Annual turnover is the total ordinary income derived in the ordinary course of carrying on a business.

Generally speaking, two entities are connected with each other if one ‘controls’ the other, or both are controlled by a third entity, based on a 40% control threshold. An individual or company is affiliated with an entity if it acts, or could reasonably be expected to act, in accordance with the entity’s directions or wishes, or in concert with the entity, in relation to the affairs or the business of the individual or company.

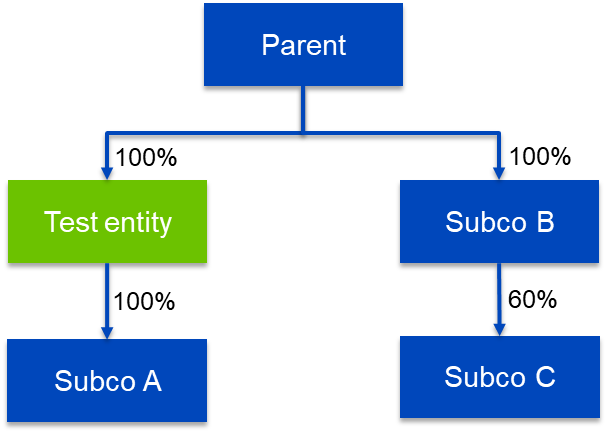

For example, an Australian subsidiary which is a member of a multinational group may need to include the turnover of an ultimate foreign resident parent company and other subsidiaries of that parent company when determining whether its aggregated turnover falls below the Turnover Threshold. In the diagram below, Parent, and Subco A, B and C, would be connected with Test Entity and their annual turnovers would need to taken into account in considering whether it satisfied the Turnover Threshold.

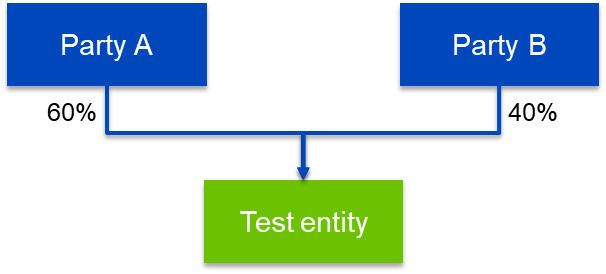

Where an Australian entity is owned by two or more parties (e.g. an incorporated joint venture) it may be necessary to include the turnover of any of those parties that hold at least 40% of the interests in the entity. For example, in the following diagram, Test Entity would need to include Party A’s annual turnover in considering whether it satisfied the Turnover Threshold:

Although Party B holds 40% and, therefore, also controls Test Entity, it would be open to Test Entity to apply to the Commissioner of Taxation to exercise his discretion to determine that Party B does not control Test Entity if he considers that another entity (e.g. Party A) controls Test Entity.

While the above examples are in the context of corporate groups, the principles to determine control and, therefore, aggregated turnover, are equally applicable to other types of entities.

Sunset date of 30 June 2022

The full expensing measure will only available in respect of depreciating assets which are first used or installed ready for use between 6 October 2020 and 30 June 2022. Given typical long planning and design lead times for infrastructure projects, this measure may not be available for some of the projects announced in the Budget. As noted earlier, however, many of the Government’s proposed road and rail projects are shovel ready and can theoretically commence within the next six months. The measure also applies to improvements to existing eligible depreciating assets.

Loss carry-back

The second important Budget measure relates to loss carry-back.

Corporate tax entities with an aggregated turnover of less than $5 billion can now offset tax losses against previously taxed profits to generate a tax refund. This will allow eligible corporate tax entities that paid tax in previous years to utilise their current losses in respect of such previous years, rather than carry them forward.

Under this change, a corporate tax entity will be allowed to carry back a tax loss for the 2019-20, 2020-21 or 2021-22 income year and apply it against tax paid in a previous income year as far back as the 2018-19 income year. The temporary loss carry-back rules will cease to apply after the 2021-22 income year.

Given the typical tax profile of infrastructure projects where tax losses are made in the earlier stages of the project, it is unlikely that this measure will be of material benefit to infrastructure investors.

It would have been of greater value to infrastructure investors had the Federal Government sought to address issues relating to the carrying forward of losses in infrastructure projects. For example, where a trust invests in infrastructure and makes losses, the ability of the trust to carry forward and utilise those losses is subject to the trust loss rules. These are difficult to apply in practice and typically require consideration of whether the trust is a ‘fixed trust’ for tax purposes. Furthermore, unlike companies, there is no secondary business continuity test for a trust to fall back on where there has been a majority change in ownership of the trust.

Concluding comments

Investment in infrastructure is likely to remain a critical component of Australia’s plan for economic recovery going forward. The taxation of infrastructure projects is a complex affair at the best of times and the changes proposed by the Budget, while potentially favourable, will require careful consideration to determine their availability.

If the Government is committed to building Australia’s infrastructure, not only to mitigate the economic impact of COVID-19 but to drive productivity growth and to maintain and enhance our standard of living, the taxation framework underpinning investment in infrastructure should be examined more broadly.

Would you like the learn more about the Federal Budget changes and what they mean for infrastructure projects? Reach out to Gilbert + Tobin’s tax team who will be able to guide you through these measures and the benefits your business may receive.

Visit Smart Counsel